Reading from the Book of Numbers

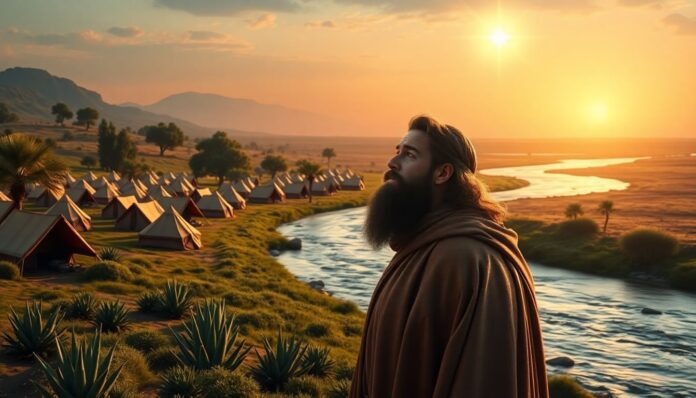

In those days, the pagan prophet Balaam looked up and saw Israel encamped in tribes. The Spirit of God came upon him, and he uttered these mysterious words: «The oracle of Balaam son of Beor, the oracle of the keen-eyed man, the oracle of one who hears the words of God. He sees what the Almighty reveals to him, he is in a trance, and his eyes are opened. How beautiful are your tents, Jacob, and your dwellings, Israel! They spread out like valleys, like gardens beside a river; the Lord planted them like aloes, like cedars beside the waters! A mighty man will come from the line of Jacob; he will rule over many peoples. His kingdom will be greater than Gog’s, and his kingdom will be exalted.»

Balaam uttered these mysterious words: «The oracle of Balaam son of Beor, the oracle of the keen-eyed man, the oracle of him who hears the words of God, who has the knowledge of the Most High. He sees what the Almighty reveals to him, he is filled with wonder, and his eyes are opened. This mighty man I see—but not for now—I behold him—but not near: A star shall rise out of Jacob, a scepter shall be set out of Israel.»

When God speaks through the mouth of the foreigner: the prophecy of Balaam and the messianic hope

A pagan prophet reveals God's plan for Israel and announces the coming of a universal king.

Imagine a man who does not belong to the chosen people, a hired soothsayer summoned to curse Israel, who suddenly finds himself the spokesperson for God's most radiant promise. This paradoxical situation is not a narrative accident: it reveals a fundamental truth about how God works in human history. The text of Numbers that we are exploring today overturns our usual categories and invites us to recognize that the divine Word can emerge from the most unexpected places. This study is for all those who seek to understand how God leads humanity toward its fulfillment, and how the messianic promise transcends the ages to illuminate our present.

We will begin by exploring the historical and literary context of this enigmatic prophecy, before analyzing the paradox of a pagan prophet inspired by the Spirit. We will then delve into three major dimensions: the universality of the divine plan, the beauty of the chosen people in God's eyes, and the promise of a messianic king. Finally, we will consider how the Christian tradition has received and reflected upon this text, before offering concrete suggestions for our spiritual journey.

The reluctant prophet

THE Book of Numbers This recounts a pivotal period in the history of Israel: the long desert march between the Exodus from Egypt and the entry into the Promised Land. Chapter twenty-two begins the Balaam cycle, one of the most unique narratives in the entire Torah. Israel is encamped in the Moabite steppes, at the gates of the Promised Land, and their large numbers terrify Balak, the Moabite king. He calls upon Balaam, a renowned seer from Mesopotamia, to curse this invading people.

The unique character of Balaam deserves attention. He does not belong to Israel; he comes from Petor, near the Euphrates, a region associated with divination and magical practices. In the ancient world, professional diviners like Balaam enjoyed considerable prestige. They were consulted to influence destiny, to attract blessings, or to bring about curses. Balak even dangles the promise of wealth and honor before Balaam if he agrees to pronounce curses against Israel. Yet, despite his evident greed in the narrative, Balaam proves incapable of cursing those whom God has blessed.

The liturgical text we are studying corresponds to the second and third oracles of Balaam, taken from a set of four successive proclamations. Each oracle follows a dramatic progression: Balaam tries to curse, but can only bless. The introductory formula emphasizes the inspired nature of his words. He presents himself as the one who hears the words of God, who sees what the Almighty shows him, who falls into ecstasy, and whose eyes are opened. These technical expressions recall the prophetic experience as Israel knows it, but applied to a foreigner.

The mention of the Spirit of God coming upon Balaam is a major theological element. In the Hebrew tradition, the Spirit of God refers to the divine power that seizes prophets, judges, and kings to accomplish a specific mission. That this spirit should possess a pagan reveals God's absolute sovereignty: he chooses his instruments according to his own will, without being constrained by ethnic or religious boundaries. This irruption of the Spirit transforms Balaam into a genuine prophet, against his will, against his material interests, in service of a design that transcends him.

The literary framework itself is of paramount importance. The text unfolds in two movements. First, an oracle of blessing celebrates the beauty of Israel's encampment, compared to verdant valleys, lush gardens, and trees planted by God by the waters. Then, a second oracle announces the coming of a hero, a star born of Jacob, a scepter rising from Israel. This transition from present contemplation to future vision structures the entire passage. Balaam first sees what is there, before his eyes, then his prophetic gaze pierces the future and glimpses the one who is to come.

The imagery employed deserves closer examination. The star and the scepter allude to royalty. In the ancient Near East, kings were regularly associated with celestial bodies, symbols of permanence, guidance, and dominion. The scepter explicitly designates the emblem of royal power. This announcement of a future king, within the context of Numbers, takes on a clear messianic character for a Christian interpretation, but already carried a considerable weight of hope within the expectations of Israel.

Prophetic speech beyond borders

The analysis of this passage reveals a profound theological dynamic that overturns our familiar categories. At the heart of this text lies a living paradox: Balaam, the pagan mercenary seer, becomes the spokesperson for the highest divine truth. This seemingly absurd situation actually illuminates an essential dimension of how God acts in history.

Balaam represents everything Israel typically rejects: a foreigner, a practitioner of divination, a greedy man ready to sell his services to the highest bidder. The Deuteronomic laws explicitly condemn divination and magical practices. Yet, it is through this man that one of the most luminous prophecies in the entire Torah resounds. This narrative irony is not accidental: it manifests God's absolute freedom. The Lord cannot be confined by any system, not even a religious one. He can bring forth truth wherever he sees fit, even among those who seem furthest from his covenant.

This universal dimension of the text deserves our full attention. God speaks to Balaam, inspires him, and imparts His wisdom to him. The pagan prophet declares that he possesses the knowledge of the Most High, that he sees what the Almighty shows him. These statements place his experience on the same level as that of the great prophets of Israel. Amos, Isaiah, and Jeremiah will speak in similar terms of their calling. The text thus rejects any monopolization of divine revelation. Certainly, Israel remains the people of the covenant, the one Balaam contemplates with wonder, but the divine Word can spring forth from everywhere.

This truth has immense implications for our understanding of God's action in the world. It liberates us from a tribal or sectarian view of faith. If God can speak through Balaam, then no one can claim to possess the exclusive right to truth. The voice of the Spirit can resound in unexpected places. This recognition does not lead to relativism: Balaam himself acknowledges that he can only bless the one whom God has blessed. But it opens us to a broader, more attentive listening to the signs of divine presence beyond our denominational or cultural boundaries.

The text also underscores the involuntary nature of Balaam's prophecy. He comes to curse, he is paid to curse, his material self-interest compels him to curse. But he can only bless. This powerlessness of the prophet before the Word that compels him reveals the absolute transcendence of the prophetic message. The authentic word of God cannot be manipulated, bought, or instrumentalized. It bursts forth with an irresistible force that overcomes all human resistance. Balaam experiences firsthand what it means to be a prophet: not to say what one wants or what others expect, but to faithfully transmit what God reveals and proclaims.

Balaam's forced submission to divine truth opens a meditation on conversion. The pagan prophet does not convert to Israel, he does not join the chosen people, he does not become a believer in the fullest sense of the word. Yet, for a fleeting moment, he is seized by the Spirit and becomes an instrument of revelation. This extreme experience prompts us to ask: how often does truth pass through us without our truly embracing it? How often do we proclaim righteous words without embodying them in our lives? Balaam embodies this unsettling figure of the reluctant witness, the prophet of a day whose life does not correspond to the message he carries.

The universality of the divine plan and its mediations

The first thematic axis that unfolds in our text concerns the radical universality of God's plan. Balaam, as an inspired pagan, becomes the living symbol of a fundamental truth: the Lord of Israel is also the Lord of all nations, and his plan encompasses all of humanity. This affirmation does not stem from abstract universalism or weak tolerance. On the contrary, it is rooted in the very logic of the covenant.

From the moment Abraham was called, the Lord announced that all the families of the earth would be blessed in him. This promise runs like a thread through all of sacred history. Israel is not chosen for its own sake, as an exclusive privilege, but to become an instrument of universal blessing. The choice of Israel and the openness to the nations are therefore not contradictory: they constitute two sides of the same theological reality. Balaam, the foreigner who blesses, foreshadows this movement of openness that will be fully realized in Christian revelation.

This universality is expressed first and foremost by the very fact that God speaks to Balaam. The Lord enters into dialogue with this pagan, appears to him, and communicates his will. This divine condescension reveals that no one is excluded a priori from a relationship with the Most High. Certainly, the Sinaitic covenant creates a particular bond between God and Israel, but this particularity does not exclude other forms of relationship. The Lord can reveal himself to whomever he wills, whenever he wills, and however he wills. This sovereign freedom permeates all of Scripture: Melchizedek, priest of the Most High God, who blesses Abraham; ; Ruth the Moabite integrated into the messianic genealogy; the Roman centurion whose faith Jesus marvels.

Balaam's gaze upon Israel then reveals another dimension of this universality. He contemplates the chosen people from the outside, with the eyes of a pagan, and this external perspective reveals something essential. Balaam sees the beauty of Israel, its blessing, its spiritual fruitfulness. He discerns what the Israelites themselves, absorbed in their murmuring and rebellions in the desert, sometimes struggle to recognize. This external perspective possesses irreplaceable value: it teaches us that others can see in us signs of the divine presence that we ourselves do not perceive. Otherness thus becomes a place of revelation.

This dynamic applies today to our way of inhabiting the world. If God spoke through Balaam, then we must remain attentive to the words of truth that may arise from unexpected mouths. Christians do not hold a monopoly on wisdom, justice, compassion. The Spirit blows where it wills, and we must cultivate this. humility which recognizes the seeds of the Word scattered throughout all cultures, all spiritual traditions, all human quests for meaning. This openness implies no syncretism: on the contrary, it stems from faith in a God who created all, who never abandons his creatures and sows traces of his presence everywhere.

Divine universality thus calls for a renewed attentiveness to the world. Too often, believers retreat into a defensive posture, convinced that any external truth threatens their faith. The example of Balaam frees us from this fear. Balak wanted to destroy Israel through a curse; God transformed this attempt into an abundant blessing. Similarly, what we perceive as hostile or foreign can become, through divine providence, an opportunity for grace and growth. This confidence does not arise from blissful naiveté, but from a robust faith in God's absolute sovereignty over history.

Finally, this universality finds its fulfillment in the messianic proclamation. The coming king, the star that came from Jacob, will not only reign over Israel but will rule over many peoples. His kingship will be exalted beyond all earthly kingships. This promise, read in the light of Christ, reveals its full scope: the Messiah has come to gather into unity the scattered children of God, to tear down the walls of separation, to create a new humanity where there is no longer Jew or Greek, slave or free. Balaam, a prophet for a day, glimpsed this reality fifteen centuries before it was manifested in the Incarnation.

The beauty of God's people as seen from the outside

The second thematic axis that structures our passage lies in the awestruck contemplation of Israel's beauty. Balaam, raising his eyes, sees the encampment of the chosen people and exclaims: "How beautiful are your tents, Jacob, and your dwellings, Israel!" This exclamation is not a mere aesthetic compliment. It reveals an essential theological dimension: the people whom God blesses radiate a beauty that transcends them and attracts the gaze of the nations.

The images used by the prophet deserve close attention. Israel is compared to wide valleys, to gardens by a river, to aloes and cedars planted by the Lord by the waters. These plant and water metaphors contrast sharply with the immediate geographical reality. The people are encamped in the arid steppes of Moab, a region of drought and desolation. But Balaam does not see poverty external: he contemplates the spiritual reality, the inner fruitfulness that God communicates to his people.

This prophetic vision teaches us a renewed perspective on the Church and the community of believers. From the outside, the assembly of the faithful may appear mediocre, fragile, marked by the sins and divisions of its members. Yet, in the eyes of faith, It remains this garden planted by God, irrigated by the living waters of the Spirit, bearing fruits of holiness that nourish the world. This hidden beauty often escapes superficial glances, but it is no less real. Balaam teaches us to see with God's eyes.

Water plays a central symbolic role in these metaphors. The gardens are on the banks of a river, the trees are planted by the water's edge. In the desert context of Middle East In ancient times, water symbolized life, fertility, and divine blessing. An irrigated garden represented abundance, prosperity, and stability. Transposed to a spiritual level, this image evokes grace divine water that nourishes the soul of the believer and the community. Without this constant nourishment, everything withers and dies. But where the living water of the Spirit flows, life abounds.

The trees mentioned, aloes and cedars, also possess symbolic significance. The cedar of Lebanon, In particular, the cedar tree represents throughout the Bible strength, majesty, and permanence. The cedar does not rot; it withstands the elements and reaches toward the heavens. Israel is like a cedar planted by God: rooted in the covenant, it weathers the storms of history without being uprooted. This image prophesies the enduring nature of God's people despite persecution, exile, and trials. It also foreshadows the solidity of the Church, built upon the rock, against which the forces of death will not prevail.

The beauty Balaam beheld was not static. It was accompanied by a promise of fruitfulness and expansion. Valleys widened, gardens multiplied, and trees grew. God's people were not confined to a fixed perfection; they were called to grow, to develop, and to bear ever more fruit. This dynamic of growth runs throughout the history of salvation, from the promise made to Abraham of numerous descendants to the universal mission entrusted to the disciples of Christ.

Balaam's perspective on Israel also challenges us in how we perceive others. Too often, we judge our brothers and sisters according to superficial criteria, dwelling on their visible flaws and scorning their apparent mediocrity. The pagan prophet teaches us a different way of seeing, one that seeks and recognizes hidden beauty, the work of God in a human life. Every person we meet is potentially that garden planted by the Lord, that tree nourished by his grace. Our eyes must learn to discern this spiritual beauty beneath sometimes deceptive appearances.

Finally, this contemplation of the beauty of Israel has a missionary dimension. If God's people radiate such splendor that it even amazes their enemies, then they become a sign for the nations. The beauty of the holiness It attracts, fascinates, converts. The first Christians conquered the Roman Empire not by force but by the influence of their charity, of their unity, of their hope. Even today, the Church evangelizes first by what she is before evangelizing by what she says. The coherence between the message and life, the beauty of an existence transfigured by divine love—this is what opens hearts to faith.

The rising star: promise and hope

The third thematic axis culminates in the prophetic announcement itself: "A star will rise from Jacob, a scepter will be raised from Israel." These enigmatic words, spoken by Balaam at the threshold of the Promised Land, nourished the hope of Israel for centuries and find their fulfillment in the person of Christ. They deserve in-depth analysis both for their original meaning and for their messianic significance.

In the immediate context of Numbers, this prophecy announces the establishment of the monarchy in Israel. The hero who will emerge from Jacob's descendants likely refers to David, the first great king of Israel, the one who unified the kingdom and made it shine among neighboring nations. The oracle evokes his dominion over numerous peoples, his exalted kingship. This historical interpretation has its legitimacy: Balaam prophesies the near future, the emergence of a powerful monarchy that will fulfill divine promises.

But the text goes far beyond this initial meaning. The image of the rising star, in particular, opens up much broader horizons. In the biblical tradition, the star evokes celestial permanence, the light that guides in the darkness, the manifestation of divine glory. Psalms and prophets will take up this symbolism to designate the ideal king, the awaited Messiah. Balaam sees this hero, but not for now; he glimpses him, but not up close. This temporal distance underscores the eschatological nature of the vision: it concerns a future fulfillment, an event that transcends immediate history.

Post-biblical Jewish tradition has extensively meditated on this prophecy from a messianic perspective. At the time of Bar Kokhba's revolt against Rome in the second century CE, the rebel leader was nicknamed Bar Kokhba, son of the star, in direct reference to Balaam's oracle. This identification shows how much this text fueled the hope for a political and religious liberator. If Christians Although they recognized the Messiah in Jesus of Nazareth, the Jews continued to await the one whom Balaam had glimpsed.

For the first Christians, the link between Balaam's prophecy and the birth of Jesus was strikingly clear. The Gospel of Matthew recounts how wise men from the East, guided by a star, came to worship the newborn King of the Jews. This mysterious star literally fulfilled the oracle: a celestial body rose, announcing the coming of the Messianic king. The wise men, pagans like Balaam, recognized and worshipped the one whom the Jewish authorities in Jerusalem were preparing to reject. History repeated itself: it was the strangers who embraced the revelation that those close to them refused.

The scepter mentioned by Balaam explicitly evokes royal authority. But what kind of kingship does Christ exercise? Not a political domination like that of the powerful of this world, but a kingship of truth and life, of holiness and of grace. Jesus reigns through love, through service, through the gift of his life. His scepter is the cross, an instrument of torture transformed into a throne of glory. This radical inversion of human values fulfills Balaam's prophecy in an unpredictable and paradoxical way.

The universal scope of this messianic kingship deserves to be emphasized. Balaam announces that this king will rule over many peoples. The risen Christ sends his disciples throughout the world to make disciples of all nations. His lordship extends far beyond the ethnic or geographical boundaries of Israel. He is the king of the universe, the one before whom every knee will bow, in heaven, on earth, and under the earth. This universality fulfills the movement already present in Balaam's oracle: the pagan who prophesies prefigures the nations that will worship the Messiah of Israel.

The messianic hope conveyed by this text also possesses an undeniable eschatological dimension. Balaam sees this hero, but not for now. Even after the coming of Christ, even after his resurrection and ascension, the full realization of his kingship remains yet to come. We live in the intervening time: the Messiah has come, but his reign is not yet fully manifested. The star has risen, but we await the day when it will shine in all its splendor, at the glorious return of the Lord.

This tension between the already and the not-yet structures the entire Christian existence. We celebrate Christ's victory over sin and death, but we continue to struggle against evil. We taste the pledge of the Spirit, but we groan in anticipation of the redemption of our bodies. Balaam's oracle keeps us in this vigilance of hope: the king is here, among us, but we strive toward his final manifestation. This active hope prevents us from settling into a false sense of security or from despairing in the face of the trials of the present time.

Echoes in tradition

Patristic and liturgical tradition has meditated on this text of Balaam with remarkable depth. From the earliest centuries, the Church Fathers recognized in it a major prophecy of the coming of Christ and developed a rich theology from this enigmatic statement uttered by a pagan. Their spiritual reading helps us to penetrate more deeply into the meaning of this passage.

Origen, the great Alexandrian exegete of the third century, devotes lengthy sections to the oracle of Balaam in his homilies on Numbers. He emphasizes that the star seen by the prophet is none other than Christ himself, the light of the nations, the morning star that heralds the new day of salvation. This Christological identification runs throughout the entire subsequent tradition. Christ is the true star that guides people out of the darkness of ignorance and sin toward the knowledge of the living God.

Augustine, for his part, meditates at length on the paradox of Balaam. This greedy pagan, who came to curse, becomes, against his will, a prophet of truth. The Bishop of Hippo sees in this an illustration of the doctrine of grace God can bring good out of evil, transforming evil intentions into instruments of his plan. Balaam foreshadows the many figures in salvation history who, unwittingly or even unknowingly, serve God's purposes. Caiaphas prophesying the redemptive death of Jesus, Pilate proclaiming his innocence while condemning him, the Roman soldiers fulfilling the Scriptures by crucifying the Savior: all these figures echo Balaam.

The Latin liturgy has incorporated this passage into the time of Advent and of Christmas, thus highlighting its messianic and natal dimension. Balaam's oracle resonates particularly during this period of preparation and waiting. The faithful, like the prophet, scan the horizon to glimpse the rising star. They keep watch in the hope of the one who is to come, the promised king whose reign will know no end. This liturgical insertion is not an arbitrary choice: it manifests the profound unity between the expectation of Israel and the expectation of the Church.

Medieval hymns and sequences frequently employ the image of Jacob's star. In the famous Veni Emmanuel, the people sing: Come, star of the East, shed your light upon our darkness. This invocation is directly rooted in the prophecy of Balaam. The star becomes a symbol of Christian hope, a sign of loyalty divine, which fulfills its promises. Medieval churches often depict the star of Bethlehem guiding the Magi, a visible fulfillment of the prophetic word.

In his biblical commentaries, Thomas Aquinas offers a more systematic reading of the text. He distinguishes several levels of meaning: literal, allegorical, tropological, and anagogical. In the literal sense, Balaam prophesies David; in the allegorical sense, he announces Christ; in the tropological sense, he evokes the light of faith in the soul of the believer; in an anagogical sense, it prefigures the heavenly glory where the risen Christ reigns. This fourfold hermeneutic considerably enriches our understanding of the text by unfolding its full semantic depth.

Carmelite spirituality, represented in particular by John of the Cross, meditates on Balaam's oracle in the midst of the dark night. The star rising in the darkness symbolizes the theological hope that guides the soul through its trials. When all natural light is extinguished, when God seems absent, faith It remains like a distant but certain star. It assures the believer that dawn will come, that the day will break, that the final encounter with the Beloved is approaching.

Personal meditation

Having explored the theological and spiritual dimensions of Balaam's oracle, it is appropriate to suggest some concrete steps for integrating this message into our life of faith. These suggestions aim to facilitate a personal journey, adapted to each individual's pace, allowing the Word to enrich our lives.

The first step is to humbly acknowledge that God can speak through unexpected voices. Let us take time to examine our recent lives: what words of truth have we heard from non-believers, from strangers to our tradition, from people we might have despised? Has the Spirit spoken through them to instruct us, correct us, or encourage us? This recognition frees us from spiritual pride and opens us to a wider range of listening.

The second step invites us to contemplate the beauty of God's people, of which we are a part. Too often, we dwell on the Church's shortcomings, its scandals, its divisions, its mediocrities. Balaam teaches us a different perspective. Let us try to see our ecclesial community as a garden planted by God, watered by his grace. What fruits of holiness Can we discern in it? What signs of hope? This renewed contemplation nourishes our love for the Church and our commitment within it.

The third step leads us to rekindle our messianic hope. In a world marked by violence, injustice, and despair, do we truly believe that the star has risen, that the king has come, that victory is won? Let us take time for silent meditation to allow the Spirit to strengthen this certainty within us: Christ reigns, even if his reign remains hidden. Let us anchor our lives in this hope that does not disappoint.

The fourth step invites us to reflect on our own prophetic vocation. Through baptism, we are all configured to Christ, priest, prophet, and king. Like Balaam against his will, we are called to proclaim divine truth within our own life context. Where and how can we be spokespeople for divine blessing today? To whom is our witness particularly sought? Let us ask. grace of prophetic audacity.

The fifth step invites us to examine our conscience regarding the universality of salvation. Do we tend to confine God within our narrow categories? Do we refuse to recognize his action beyond the visible boundaries of the Church? Let us pray that our hearts may expand to the dimensions of God's heart, which desires that all people be saved and come to the knowledge of the truth.

The sixth step involves specifically identifying a person we tend to despise or judge negatively, and asking grace to see in it this garden planted by God, this tree nourished by his providence. Perhaps then we will discover unsuspected qualities, unexpected lights, signs of divine presence that our usual gaze did not perceive.

The seventh step, finally, invites us to look to the future with confidence. Balaam sees the star, but not for now; he glimpses it, but not closely. We too live in this time of waiting and vigilance. Let us ask grace of perseverance, the strength to hold fast in hope, the light to discern already in our present the harbingers of the coming reign.

A prophetic message for today

Balaam's oracle, uttered more than three millennia ago in the steppes of Moab, has lost none of its powerful challenge. On the contrary, it resonates with striking relevance in our contemporary world, a world torn by tensions between particularism and universalism, between identity and openness, between hope and despair. This text calls us to a conversion of both perspective and heart.

His first lesson concerns our relationship to otherness. In a context marked by identity politics, closed communities, and fears of the other, Balaam teaches us that the stranger can become a bearer of truth. This recognition does not lead to a weak relativism that would deny the specificity of Christian revelation. Rather, it invites us to a respectful and attentive listening to all spiritual traditions, to a sincere dialogue that seeks and welcomes the seeds of the Word scattered throughout the world. The Spirit blows where it wills: this Johannine affirmation finds a prophetic illustration in the inspired words of the pagan seer.

The second lesson concerns our ecclesiology. Faced with the scandals that disfigure the Church, the divisions that tear it apart, and the mediocrity that paralyzes it, the temptation of disgust or despair lies in wait for us. Balaam reminds us that the beauty of the Church does not reside in the moral perfection of its members but in grace divine water that constantly nourishes it. Like the garden by the river, it lives on this living water that Christ promised and that the Spirit imparts. Our gaze must learn to discern this holiness Hidden, this spiritual fecundity remains even when appearances seem to contradict it.

The third lesson concerns our eschatological hope. The star has risen in Jesus Christ, but his reign remains veiled, contested, and ignored by the majority of humanity. This situation could lead us to discouragement. Yet, Balaam's prophecy reminds us that God's timing is not our timing, that his patience surpasses our impatience, that his plan unfolds according to a logic that often eludes us. The prophet sees the hero, but not for now. This temporal distance teaches us the virtue of active waiting, patient vigilance, and unwavering hope.

The call that springs from this text is therefore multifaceted yet convergent. It invites us to step out of our comfortable certainties to welcome God's newness, to purify our vision to contemplate the hidden beauty of his work, to rekindle our hope to persevere through the night while awaiting the day. This threefold conversion—of mind, heart, and will—makes us open to the transforming action of the Spirit. It makes us prophets for our time, capable of discerning and proclaiming the signs of the Kingdom's presence in the midst of our troubled history.

May this enigmatic oracle, spoken by an inspired pagan at the gates of the Promised Land, become for us a source of spiritual renewal. May it help us to broaden our perspective, strengthen our hope, and live our prophetic vocation with boldness and humility. And above all, may it keep us in the joyful certainty that the star has risen, that the king has come, that victory is won, and that it is now up to us to bear witness to this light which will never be extinguished.

Practices

- Meditate daily on a verse from the oracle of Balaam, asking yourself how it sheds light on your present situation.

- Identify a person different from yourself and pray to discern in them the signs of divine presence.

- Dedicate some time to lectio divina weekly magazine on the messianic texts of the Old Testament.

- Keep a spiritual journal noting the times when God spoke to you through unexpected voices.

- Actively participate in interfaith meetings to deepen your understanding of the universal action of the Spirit.

- Regularly contemplate an icon of Christ Pantocrator to nourish your hope in his universal kingship.

- Engage in a work of charity concrete as a prophetic sign of the coming Kingdom.

References

- Book of Numbers, chapters twenty-two to twenty-four, complete narrative of the Balaam cycle.

- Gospel according to Saint Matthew, chapter two, story of the Magi guided by the star.

- Psalm seventy-two, a messianic royal oracle resonating with the prophecy of Balaam.

- Origen of Alexandria, Homilies on Numbers, patristic exegesis of the Balaam cycle.

- Augustine of Hippo, The City of God, meditation on divine providence and the prophets in spite of themselves.

- John of the Cross, The Dark Night, symbolism of the star in spiritual ordeal.

- Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica and Biblical Commentaries, Fourfold Hermeneutics of Prophecy.

- Lumen Gentium Dogmatic Constitution of Vatican II Council, ecclesiology of communion and universal mission.