Gospel of Jesus Christ according to Saint Matthew

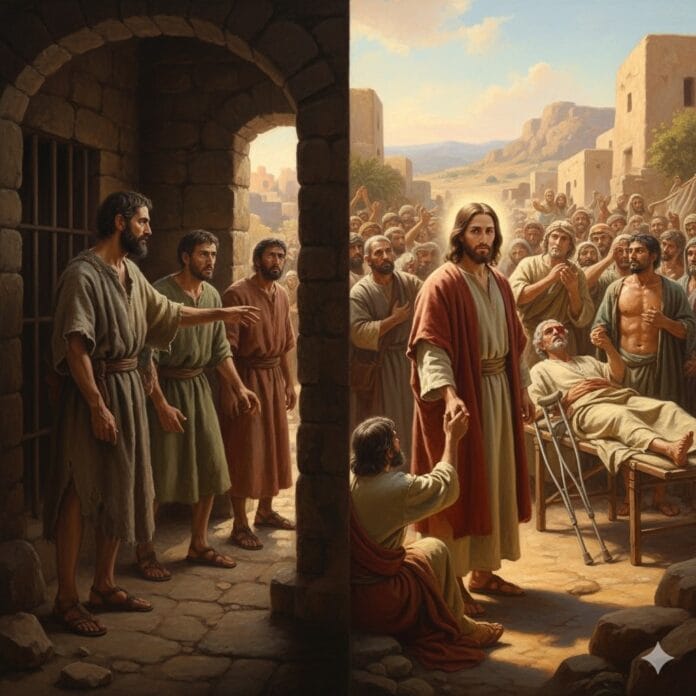

At that time, John the Baptist learned, in his prison, The works accomplished by Christ. He sent his disciples to him and, through them, sent word to him: «Are you the one who is to come, or should we…?” to wait for Another one?» Jesus answered them, «Go and report to John what you hear and see: The blind receive their sight, the lame walk, those who have leprosy are cleansed, the deaf hear, the dead are raised, and the poor receive the Good News. Blessed is the one who does not stumble on account of me!»

As John's messengers were leaving, Jesus began to speak to the crowds about John: «What did you go out into the wilderness to see? A reed shaken by the wind? Then what did you go out to see? A man dressed in fine clothes? But those who wear fine clothes live in kings' palaces. Then what did you go out to see? A prophet? Yes, I tell you, and more than a prophet. This is the one about whom it is written: ‘See, I am sending my messenger ahead of you, who will prepare your way before you.’ Truly I tell you, among those born of women there has not risen anyone greater than John the Baptist ; And yet the least in the kingdom of heaven is greater than he.»

Recognizing the Messiah in the midst of doubt: when expectation meets reality

The Gospel of John the Baptist in prison teaches us to discern God's presence where we did not expect it.

You are in the middle Advent, This time of waiting and hoping, and yet something wavers within you. The promises seem delayed, the signs you seek do not come as expected, and even your strongest faith experiences moments of questioning. John the Baptist, The man who had recognized Jesus in the Jordan, the one who had proclaimed "Behold the Lamb of God," finds himself in prison and sends his disciples to ask, «Are you the one who is to come, or should we to wait for "Another one?" This question, far from being a spiritual failure, opens a path of mature faith that integrates doubt, welcomes God's discreet signs, and invites us to recognize a Messiah who comes in a different way than expected.

We will first explore the dramatic context of Jean in prison and the theological legitimacy of his question, then we will analyze Jesus' response, which refers to the prophecies of Isaiah. We will then explore three major themes: doubt as a space for spiritual growth, messianic signs versus our expectations, and the paradoxical grandeur of the Kingdom. Finally, we will outline concrete applications, a path for meditation, and responses to current challenges, before concluding with a liturgical prayer and practical guidelines.

The Prophet in Prison: Contextualizing John's Question

John the Baptist, a leading figure in the conversion movement in the desert, has just been arrested by Herod Antipas for denouncing his illegitimate marriage to Herodias. Matthew places this episode after the baptism of Jesus (Mt 3, 13-17) and the beginning of the Galilean ministry. John, imprisoned in the fortress of Machaerus east of the Dead Sea, hears about "the works done by Christ." The Greek expression ta erga tou Christou (the works of the Messiah) is heavy with meaning: it indicates that John perceives a messianic dimension in the action of Jesus, but that he questions its exact nature.

The liturgical context of this passage, proclaimed on the third Sunday of Advent, is part of a dramatic progression. The first Sunday invites us to be vigilant, the second to convert, and the third, marked by the color rose and the antiphon Gaudete (Rejoice), seems paradoxical: we celebrate joy while Jean doubts prison. This tension reveals a profound spiritual truth: joy Christian does not exclude honest questioning, it incorporates it.

The messianic expectation in the first century was laden with political and military hopes. The intertestamental writings, the Psalms of Solomon, the Qumran manuscripts, all bear witness to an expectation of a Davidic Messiah who would restore the kingdom of Israel, drive out the Roman occupiers, and establish a reign of justice by force. John himself had foretold an implacable judge: «The ax is already laid to the root of the trees» (Mt 3, 10). Now Jesus heals, teaches, and shares meals with the fishermen, but he brandishes no weapon, he summons no heavenly army.

John's doubt, therefore, does not concern the general identity of Jesus, but rather the consistency between what he does and what the Messiah was supposed to accomplish. It is an intelligent, theologically informed doubt, arising from the confrontation between received tradition and the radical newness of Jesus. John here embodies the Old Testament at its zenith: the last and greatest of the prophets, yet still on the threshold of the Kingdom. His question is not a lack of faith, but a faith that seeks understanding.

The Alleluia preceding the Gospel quotes Isaiah 61:1: «The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has sent me to bring good news to the poor.» This verse sets the stage for Jesus’ response and guides our reading: the Messiah is recognized not by his coercive power, but by his closeness to the lowly and the broken. The liturgy juxtaposes John’s question with the key to understanding from Isaiah, inviting the faithful to adjust their perspective.

The signs of Isaiah as an answer: analyzing the Christological strategy of Jesus

Jesus does not answer with a yes or a no. He does not proclaim "I am the Messiah," nor does he cite a Christological title. His response is narrative and performative: "Go and tell John what you hear and see." This formula refers to sensory experience, to concrete testimony, rather than to abstract dogmatic adherence. Jesus then lists six signs that weave together Isaiah 29, 18-19; 35, 5-6 and 61, 1: the blind see, the lame walk, the lepers are cleansed, the deaf hear, the dead are raised, the poor they receive the Good News.

This list is not random. It echoes the Isaiah oracles concerning the eschatological restoration of Israel, but with a decisive shift. In Isaiah, these signs accompany the return from exile, the restoration of the Temple, and the glorious coming of God. Jesus actualizes them in his itinerant ministry, far from the structures of power. The verb "to resurrect" (egeirô) used for the dead is the same as when talking about the resurrection of Jesus, creating a bridge between the present signs and the coming Easter victory.

The climax of the list is significant:« the poor receive the Good News» (ptôchoi euangelizontai). This is not simply another miracle, it is the summarizing sign. The poor, ptôchoi, In the Matthean context, these refer to those who are materially destitute, but also to the humble of heart, the anawim from biblical tradition. The proclamation of the Good News to the poor fulfills Isaiah 61:1 and inaugurates the Messianic Jubilee, the year of the Lord's grace.

The beatitude that concludes the response—"Blessed is the one who does not stumble on account of me"—is a delicate invitation to discernment. The term Skandalon (stumbling block) evokes the possibility of Jesus being rejected precisely because he does not conform to conventional messianic expectations. Jesus implicitly acknowledges that his way of being the Messiah may disappoint, scandalize, or be an obstacle. It is a humility remarkable Christological approach: it does not impose itself, it proposes, and blesses those who agree to revise their categories.

The rhetorical structure of the response is also instructive. Jesus begins with the senses (sight, hearing), moves to the body (walking, being purified), touches on life and death (resurrection), and culminates in the word (receiving the Good News). It is a holistic anthropology: salvation touches all dimensions of the human being. It is neither a spiritualist salvation that would disregard the body, nor a purely political messianism that would ignore inner conversion.

Taming doubt: when faith questions without dissolving

John the Baptist in prison embodies the condition of the believer who traverses darkness without losing their fundamental direction. Their doubt is neither skepticism nor denial; it is a questioning carried by faith herself. He doesn't ask "Who are you?" but "Are you the one "Who is supposed to come?", which presupposes that there is indeed someone to to wait for. Jean's doubt is a doubt In faith, No doubt about it. against faith.

This distinction is crucial for spiritual life. The Christian tradition, of Saint Augustine (« Crede ut intelligas, intellige ut credas »– Believe to understand, understand to believe) to John Paul II (encyclical) Fides and Ratio), has always valued intellectual research and honest questioning. Methodical doubt, the kind that seeks to delve deeper, is not the enemy of faith, He is often her traveling companion. Saint Thérèse of Lisieux herself, a Doctor of the Church, experienced terrible trials of doubt in her last years, crying out to God in the midst of darkness.

In the context of his imprisonment, John's doubt takes on an existential dimension. He is no longer on the banks of the Jordan, free to proclaim, baptize, and bear witness. He is locked up, destitute, perhaps morally tortured by the lack of visible results. Desert Fathers taught that the’acedia (Spiritual discouragement) often arises in forced immobility, when action is blocked. John experienced this. His question also stemmed from concrete suffering: why doesn't the Messiah set me free?

Jesus doesn't reproach John at all. On the contrary, as soon as John's disciples have left, he offers his most fervent praise: "Among those born of women, there has not risen anyone greater than John the Baptist. This means that John's doubt does not negate his greatness. God does not reject those who doubt while sincerely seeking. Faith Christian faith does not demand unwavering certainty at every moment; it demands a fidelity that persists even in uncertainty.

This lesson is liberating for many contemporary believers. How many feel guilty about their doubts, thinking they are betraying God or disappointing their community? Matthew's text allows for a more human, more embodied faith. We can ask the question, "Are you really there? Are you really at work?" while remaining in the dynamic of seeking and waiting. Saint Anselm spoke of fides quaerens intellectum, faith who seeks intelligence. John embodies this questioning faith.

Jesus' response through the Isaiah signs also indicates a divine pedagogy: God reveals himself gradually, through his works, not through irrefutable proof. He leaves room for doubt, for freedom. If Jesus had responded with a dazzling miracle that immediately freed John, it would have been a constraint, not an invitation. By referring John to the subtle signs—the blind, the lame, the poor —, Jesus invites him to a finer, more contemplative discernment.

There is also an eschatological dimension. John represents the threshold: "the greatest of those born of women," but "the least in the kingdom of heaven is greater than he." This means that John still belongs to the time of promise, while Jesus' disciples are entering the time of fulfillment. John's doubt marks this transition. He senses that something new is emerging, but he cannot yet fully grasp it. We too, between the already and the not yet, sometimes oscillate between recognition and questioning.

Recognizing subtle signs: beyond spectacular expectations

The signs Jesus enumerates are real, tangible, and verifiable by John's messengers. They are not abstract concepts or futuristic promises; they are healings and liberations happening here and now. Yet, they do not fit the expected pattern. John, like many of his contemporaries, expected immediate judgment, purification by fire, and a radical separation between righteous and wicked. But Jesus heals the sick, eats with tax collectors, and announces mercy.

This tension between expectation and reality runs throughout the history of salvation. The disciples on the road to Emmaus hoped that Jesus would "deliver Israel" (Lk 24:21), and they are disoriented by the cross. The apostles before the Ascension still ask: "Are you now going to restore the kingdom to Israel?"Ac 1, 6). The Apocalypse It is itself written for communities that await the Parousia and that must learn to live in patience. Recognizing God's signs therefore requires a constant adjustment of our expectations.

The Isaiah signs that Jesus quotes have a profound theological significance. They are not mere miracles to prove an identity; they are the inauguration of a new creation. When the blind see, it is Genesis 1 which begins again: "Let there be light." When the dead are resurrected, it is victory over the Adamic curse. When the poor When they receive the Good News, it is the Jubilee of Leviticus 25 that is fulfilled: the remission of debts, the liberation of captives. These signs are therefore not mere proofs; they are the very event of salvation in action.

Saint Augustine, in its Tractatus in Ioannem, explains that the miracles of Jesus are signa, signs that point to a deeper reality. Curing a physically blind person also means opening their eyes. faith ; resurrecting Lazarus announces the resurrection of the soul dead through sin. There is therefore a double reading: historical (healings really did take place) and symbolic (they signify complete salvation).

In our contemporary context, the temptation is twofold. On the one hand, a rationalism that believes only in what is scientifically verifiable and rejects the supernatural. On the other, a fideism that expects spectacular events and becomes discouraged when God acts discreetly. The Gospel of Matthew 11 invites us to a supernatural realism: God really acts, but often in a humble way, on the peripheries, with the little ones.

Recognizing these signs requires a contemplative heart. How often do we miss God's presence because it doesn't resemble what we imagined? Family reconciliation is a sign of resurrection. A freely given act of forgiveness is a purification. A word of hope spoken to a poor person is the proclamation of the Good News. The signs of the Kingdom are there, but we need eyes to see them. Faith, As the Epistle to the Hebrews (11:1) says, it is "the evidence of things not seen." It discerns the presence of God in the transfigured ordinary.

Paradoxical greatness: being greater by being smaller

The final paradox of our passage is striking: «Among those born of a woman, no one has arisen greater than John the Baptist ; "And yet the least in the kingdom of heaven is greater than he." This statement places John at the crossroads between two economies, two modes of relating to God. John is the pinnacle of the Old Testament, the eschatological prophet who prepares the way, but he remains short of the radical newness introduced by Jesus.

What makes "the least in the kingdom" greater than John? It's not a matter of personal merit or of holiness Morality. It is a question of participation in divine life. Through baptism in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, by the Eucharist, Through the indwelling of the Spirit, the Christian is grafted onto Christ, becomes a member of his Body, a co-heir of the Kingdom. John announced the Messiah; the Christian lives in him.

Saint Thomas Aquinas, in the Summa Theologica (IIa-IIae, q. 174, a. 6), distinguishes prophecy from the beatific vision. The prophets of the Old Testament knew God through signs and riddles (per speculum in aenigmate, ( , 1 Cor 13:12), while the baptized know God as Father through the Spirit who cries out in them "Abba!" (Rm 8, 15). This filial knowledge, even if imperfect here below, surpasses prophetic knowledge.

This paradox also sheds light on our condition. We are all, in a certain way, "small in the Kingdom." Neither historical apostles, nor eyewitnesses, nor martyrs of the early centuries. Yet, our smallness is not an obstacle, it is the very place of grace. The Beatitudes they chant: "Happy the poor "In spirit, blessed are the meek, blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness." The greatness of the Kingdom is measured by the inverse of worldly standards.

Jesus himself embodies this reversal. He who is God becomes a servant, washes the feet of his disciples, and dies on a cross. Saint Paul sings of it in the hymn of Philippians 2:6-11: he "emptied himself" (ekenôsen), taking on the condition of a slave, and that is why God "exalted" him. The logic of the Kingdom is kenotic: one ascends by descending, one wins by losing, one lives by dying.

For our everyday lives, this means a radical shift in our ambitions. Seeking worldly greatness—success, recognition, power—can lead us away from the Kingdom. Accepting our smallness, our role as servants, our last, makes us available to grace. Saint Thérèse of the Child Jesus made this "little way" the path of her holiness. She used to say, "My vocation is Love." Not great actions, but small acts done with great love.

This message about paradoxical greatness also comforts those who feel insignificant. You are not John the Baptist, you don't have a dazzling ministry, you doubt, you stumble? Rejoice: in the Kingdom, that is precisely what makes you great. Your humility, Your awareness of your own insignificance, your need for God, all of this opens you to grace. The Pharisee who boasts is sent away without justification; the tax collector who beats his breast goes down justified.Luke 18, 14).

To embody expectation and discernment in everyday life

How do these theological truths translate into our ordinary lives? First, into how we inhabit doubt. If you are going through a period where faith If you falter, if God seems absent, do not condemn yourself. Imitate John: ask the question. Pray, «Are you really there?» not as a reproach, but as a genuine inquiry. Seek companions on your journey—a spiritual director, a prayer community—who will welcome your questions without judgment.

Next, in our way of discerning God's presence. Make it a habit, each evening, to reflect on your day, looking for subtle signs: an act of kindness received, a word that touched you, a reconciliation begun, a moment of unexpected peace. This is the Ignatian examination of conscience: not just counting your sins, but recognizing the consolations and promptings of the Spirit. God often acts in the small, the everyday, the humble.

Within the family, this translates into renewed attention to vulnerable members. Who is the blind person who can no longer see hope? Who is the lame person who can no longer walk? Who is the deaf person who can no longer hear others? Our homes can become places where the Good News is proclaimed through concrete actions: listening without judgment, forgiving an offense, making time for one another.

In professional life, applying this gospel means rejecting the logic of performance at all costs. The saying "the least in the kingdom" reminds us that our worth does not depend on our productivity. Working with excellence, yes, but without crushing others or destroying ourselves. Recognizing our limitations, asking for help, accepting that we cannot succeed at everything—this is to experience paradoxical greatness.

In the life of the Church, this Gospel challenges our expectations of it. We sometimes want a triumphant, powerful Church that dominates public debate. Yet Jesus invites us to recognize its action in the poor who receive the Good News. The Church is more faithful to its mission when it serves the lowly than when it seeks power. The Second Vatican Council (Lumen Gentium 8) speaks of the Church as "poor and servant".

Finally, in our relationship to waiting itself. Advent teaches us to wait for without discouraging us. Jean was waiting in prison. We wait in our stuck situations: a prolonged illness, an unresolved conflict, a delayed vocation. To wait for In Christian terms, this is not about being passive, but about remaining vigilant, seeking signs, and preparing the way. It is about doing what is possible today, entrusting the rest to God.

From patristic exegesis to modern spirituality

The Church Fathers commented extensively on this passage. Saint John Chrysostom, in his Homilies on Matthew (Homily 36) emphasizes Jesus' sensitivity towards John. He doesn't say, "Go tell John he's wrong to doubt," but rather gives him the information he needs to judge for himself. Chrysostom sees this as a pedagogical model: respecting the other's freedom, accompanying them in their search rather than imposing an answer.

Saint Ambrose of Milan, in his Comment on Luc, This scene brings us closer to Thomas's doubt after the resurrection. The two figures—John before Easter, Thomas after—illustrate that doubt can be a passage to a deeper faith. Thomas, by touching the wounds, arrives at the ultimate confession: «My Lord and my God.» John, by hearing the signs, is invited to recognize the humble Messiah.

Saint Augustine, in the De consensu Evangelistarum, This interpretation emphasizes that John does not doubt for himself, but for his disciples. This reading, adopted by Thomas Aquinas, sees John's question as a pedagogical exercise: he wants his disciples to hear from Jesus himself who he is. Thus, John's doubt would be a pedagogical doubt, a question posed for the instruction of others. This interpretation, while mitigating the scandal of the doubt, also reveals the Baptist's pastoral concern.

In the monastic tradition, this passage inspires a spirituality of contemplative waiting. Saint Benedict, in his Ruler, speaks of living "under the gaze of God," in a state of constant readiness. The monks, through their vows of stability, obedience, and conversion of morals, practice to wait for God in the ordinariness of cenobitic life. Like John in prison, They renounce external freedom in order to find inner freedom.

Carmelite spirituality, with John of the Cross, explores the dark night of faith. Jean in prison anticipates this night: God seems absent, certainties fade, one must proceed tentatively. But it is precisely in this night that faith She purifies herself, detaching herself from worldly consolations to cling to God alone. Holy Teresa of Avila speaks of "dryness" in prayer: God withdraws so that our love may grow.

In the 20th century, Hans Urs von Balthasar, in his Theology of History, John meditates on "Holy Saturday," the time when Jesus descends into hell and the disciples wait in silence. prison He lived an anticipated Holy Saturday. He announced the Messiah, he saw him, and now he waits in the darkness. This waiting is not in vain; it prepares him. the resurrection.

THE Second Vatican Council, In Dei Verbum (Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation, no. 2), reminds us that revelation is accomplished through "words and actions intrinsically linked." The signs that Jesus gives to John precisely illustrate this connection: works (healings) are inseparable from the Word (proclamation to the poor). This establishes a theology of ecclesial action: the Church proclaims through its deeds as much as through its words.

A seven-step path of personal discernment

Here's a way to meditate on this passage and integrate it into your own life. Find a quiet place and take a few deep breaths to center yourself.

First step: reread the text slowly. Let John's question resonate within you: "Are you the one who is to come?" What expectation does this question hold for you? Is there an area of your life where you ask God, "Are you truly at work here?"«

Second step: welcome your doubt. Without judgment, acknowledge the areas of uncertainty in your faith. Present them to God as John sent his disciples. Simply say, "Lord, I need signs."«

Third step: contemplate the signs. Reread the list of the six signs given by Jesus. For each one, look for an echo in your recent life. Where have you seen a blind person regain their sight (a person who has found hope again)? A lame person walk (someone who has overcome a disability)? A poor person receive the Good News (a person touched by a word of love)?

Fourth step: adjust your expectations. Identify an expectation you have that resembles John's: a Messiah who comes in power, who resolves everything immediately. Ask grace to recognize a humble Messiah, a servant, who acts in gentleness.

Fifth step: embrace your smallness. Meditate on the passage about "the least in the Kingdom." Thank God for your smallness, your limitations, your failures. Tell Him: "I am not John the Baptist, I am the least, and that is where you want to meet me."«

Sixth step: take concrete action. Inspired by the signs, choose a simple action for the coming week: visit a sick person (heal), help someone in difficulty (lift up), share the Word (proclaim). A single action is enough.

Seventh step: entrust to God. Conclude with a spontaneous prayer where you entrust your questions, your expectations, your path to God. Ask grace to remain faithful even in darkness, like John in his prison.

This meditation can be done in half an hour, or spread out over a week by taking one step per day. The key is to return to it regularly, because discernment is a journey, not a one-time event.

Addressing current objections and questions

Objection 1: How can we believe in miracles in a scientific world? The question of miracles is divisive. Some reject them as pious legends, while others seek them as proof. The Gospel invites us to a third way: the signs are real, but their truth is not limited to empirical verification. They signify a deeper reality. A blind man who sees is both a historical event (attested to by witnesses) and a theological sign (God opens the eyes of the blind). faithScience studies the how, faith search for meaning.

Objection 2: Why didn't God free John from prison ? This is the question of evil, which runs throughout the Bible. John will be beheaded a few chapters later (Matthew 14:10). Jesus did not save him physically. This reminds us that Christian salvation is not a guarantee against all risks of suffering. It is the presence of God. In Suffering, a transformation of the meaning of the ordeal. John dies a martyr, the ultimate witness to the truth. His death is not a failure, it is a fulfillment.

Objection 3: Doesn't this passive waiting encourage inaction? To wait for does not mean doing nothing. Jean in prison He never ceases to be concerned about the Messiah; he sends disciples, he questions. Christian expectation is active; it is a vigilant watch. Like the wise virgins who prepared their lamps (Mt 25), we wait by preparing, by acting, by bearing witness. Advent is a time of conversion, sharing, and solidarity.

Objection 4: Doesn't this passage reserve the Kingdom for a spiritual elite? On the contrary. Jesus says that "the least" in the Kingdom is great. This is a radical democratization of the holiness. You don't need to be a prophet, ascetic, or scholar. A baptized child, a simple person who loves, a poor person who prays—all participate in the Kingdom. Vatican He speaks of the universal call to the holiness (Lumen Gentium 5).

Objection 5: How can we distinguish true signs of God from illusions? This is the central question of discerning spirits. Saint Ignatius of Loyola proposes criteria: the true signs of God produce peace, L'’humility, charity, openness to others. False consolations breed pride, isolation, and agitation. Jesus gives a simple criterion: "By their fruits you will recognize them" (Mt 7, 20). Authentic signs bear the fruit of love, justice, and truth.

Objection 6: Does this text only concern Christians ? The signs that Jesus lists — healing the sick, Lifting up the oppressed, proclaiming justice—these are universal. Every person of goodwill who works for human dignity participates, consciously or unconsciously, in the Kingdom. The Second Vatican Council recognizes the "seeds of the Word" in all cultures (Ad Gentes 11). The Kingdom extends beyond the visible boundaries of the Church.

These answers are not definitive solutions, but rather avenues for progress. Faith Christianity is not a closed system, it is a living dialogue between God and humanity, and each generation must rearticulate this dialogue in its own language.

Prayer: Advent prayer on the threshold of Christmas

Lord Jesus, humble Messiah and servant,

you who answered John the Baptist

not through titles of glory but through signs of mercy,

teach us to recognize your presence

in the blind who find hope again,

among the lame who get up after falling,

among the excluded lepers who find their place again,

in the deaf who open themselves to your Word,

May your breath raise the dead from the dead.,

and in the poor who finally receive Good News.

We pray for those who doubt in this Advent,

for those who are waiting for you in the prison of the disease,

trapped in the cycle of injustice,

in the darkness of depression,

in the silence of your apparent withdrawal.

Let them hear your response: "Look what I'm doing,

Listen to what I announce. I am at work,

even when you can't see me.»

Grant us, Father of all consolation,

grace to embrace our insignificance,

knowing that you exalt the humble

and that you fill the hungry with good things.

Let us not seek greatness according to the world,

but the holiness hidden from faithful servants,

wise virgins who keep watch,

patient sowers awaiting the harvest.

Spirit of truth and discernment,

enlighten our eyes so we may see your signs

in everyday life these days,

in the selfless gesture of a neighbor,

in the comforting words of a friend,

In forgiveness who breaks the chains,

in the reconciliation that rebuilds bridges.

May we ourselves be signs of your Kingdom,

proclaiming through our lives the Good News of your Love.

Make us watchmen of the Dawn,

watchers awaiting your arrival,

witnesses to your tenderness for the little ones.

May even our doubts become prayer,

that our questions become research,

that our expectation may become active hope.

And when the day of your full revelation comes,

that we are found vigilant,

lamps lit, hands busy serving,

My heart burns with love for you and for our brothers.

Thus we will be able to hear the blessed word:

«Come, you who are blessed by my Father,

inherit the Kingdom

Prepared for you since the foundation of the world.»

Through Jesus Christ, the awaited and come Messiah,

with the Father and the Holy Spirit,

for centuries to come.

Amen.

On the road to recognition

The Gospel of Matthew 11, 2-11 places us at the heart of the mystery of Advent : expectation confronting reality, doubt seeking confirmation, recognition demanding an adjustment of perspective. John the Baptist, the greatest of the prophets, embodies our condition as believers: we oscillate between certainty and questioning, between clear vision and darkness, between joyful proclamation and the cry of doubt.

Jesus' answer doesn't eliminate expectation, it redirects it. It teaches us to look for God's signs not in the spectacular but in the humble service to the poor, the sick, the excluded. She reveals to us a Messiah who does not impose himself by force but who offers himself through mercy. It invites us to a mature faith, capable of integrating doubt without dissolving, of questioning without rebelling, of waiting without becoming discouraged.

The paradox of greatness—"the least in the Kingdom is greater than John"—overturns our scales of value and frees us from the obsession with performance. We don't need to be spiritual giants to enter the Kingdom. We simply need to embrace our smallness, recognize our need for God, and allow ourselves to be transformed by his grace.

In concrete terms, this Gospel calls us to three conversions. First, a conversion of perspective: seeking the signs of God in everyday life, in acts of humanity, in the quiet victories of love over hatred. Second, a conversion of expectation: moving from passive expectation to active expectation, which prepares the way, which acts for justice, which proclaims the Good News. Third, a conversion of identity: accepting to be small, a servant, last, like Jesus himself.

This Advent, Let John's question resonate within you: "Are you the one who is to come?" Ask it of Jesus in your doubts, in your trials, in your disappointments. And listen to his answer, not in a thunderous voice, but in the whisper of the signs he sows along your path. A blind man who finds hope again, that is Jesus. A lame man who gets up, that is Jesus. A poor man who receives dignity, that is Jesus. Open your eyes, listen closely, and you will recognize him.

Practices for living this gospel

- Welcome your doubts without guilt. Write them down in a prayer journal, share them with a spiritual director. Honest doubt is a place of encounter with God, not an obstacle.

- Review your day each evening, looking for three signs of God's presence. Even the smallest things: a smile, a word, a gesture. Write them down for future reference and reread them at the end of the week.

- Perform a concrete act of service this week towards a "small" or vulnerable person. Visit a sick person, listen to someone who is suffering, give your time to a charity.

- Meditate once this week the beatitudes (Matthew 5, 3-12) in parallel with this passage. Identify the links between "« the poor receive the Good News» and «Blessed the poor in spirit.".

- Pray the liturgical prayer suggested above, or compose your own inspired by the six messianic signs. Ask God to open your eyes, your ears, your heart.

- Read a text from the Church Fathers on this passage. For example, a homily by John Chrysostom or a commentary by Augustine. Allow yourself to be enriched by tradition.

- Share this gospel with your community, family or prayer group. Ask the question: "Where do we see today the signs of the Kingdom that Jesus describes?" Share your testimonies.

References

- Isaiah 35, 5-6 and 61, 1-2 : Messianic oracles taken up by Jesus in his response to John the Baptist.

- Luke 4:16-21 Jesus in the synagogue of Nazareth, proclaiming the fulfillment of Isaiah 61.

- John Chrysostom, Homilies on Matthew, homily 36 Patristic commentary on Matthew 11.

- Saint Augustine, De consensu Evangelistarum : a harmonizing reading of the gospels on the doubt of John.

- Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, IIa-IIae, q. 174 : on prophecy and the vision of God.

- Ignatius of Loyola, Spiritual exercises, rules of discernment : to distinguish between true and false consolations.

- Hans Urs von Balthasar, Theology of History : meditation on waiting and Holy Saturday.

- Second Vatican Council, Lumen Gentium And Dei Verbum : on the Church as servant and revelation through words and actions.