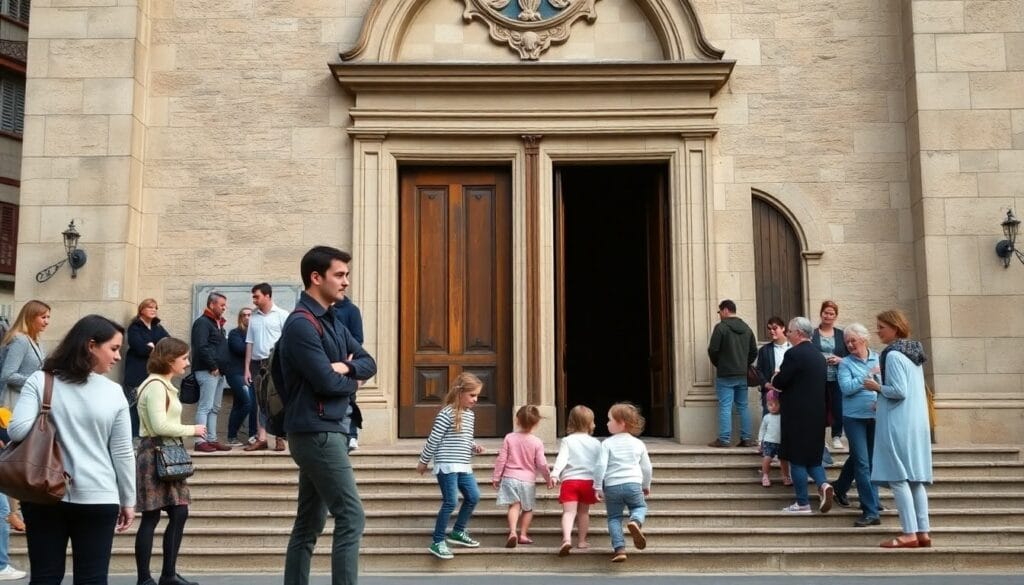

Sunday morning, 11:15 a.m., on the steps of a church in Lyon. Grégoire, 31, watches his children playing while the last notes of Gregorian chant drift from the portal. Five years ago, this young father couldn't imagine attending a Latin Mass. Today, he naturally alternates between the Ordinary Form and the Tridentine Rite, without giving it a second thought. His case? Far from unique. A recent study reveals that about two-thirds of French Catholics no longer have anything against the Traditional Latin Mass. A radical shift in a religious landscape long marked by fierce liturgical divisions.

This subtle yet profound evolution is disrupting the fault lines that have divided French Catholicism for decades. Gone are the days when attending Mass in Latin automatically pigeonholed you into a well-defined ideological category. A new generation of faithful moves freely between the two liturgical forms, drawing from each what nourishes their respective faiths. How did we get here? What does this "bi-rituality" reveal about contemporary Catholicism?

The Tridentine Mass emerges from its ideological ghetto

When the liturgy divided Catholics

To understand what is happening today, we need to go back a few decades. After the Vatican II Council (1962-1965), the liturgical reform caused considerable upheaval within the Catholic Church. On one side were the progressives who saw the Mass in French and facing the people as a necessary modernization. On the other were the traditionalists who viewed the abandonment of Latin as sacrilege and a break with Tradition.

This liturgical battle crystallized much broader oppositions regarding the vision of the Church, its relationship to the modern world, and its theological approach. Attending the Tridentine Mass was a way of sending a signal: one belonged to the conservative camp, nostalgic for a pre-modern Catholicism. Vatican He was wary of societal changes. On the other hand, exclusively attending the ordinary rite placed you among the open-minded Catholics, engaged with their times.

These divisions shaped the French Catholic landscape for decades. Traditional parishes often operated outside the diocesan structures, with their own networks, schools, and associations. A world apart, sometimes viewed with suspicion by the institution. The faithful who crossed the threshold of a church like Saint-Nicolas-du-Chardonnet in Paris or Saint-Georges in Lyon knew they were entering a distinct universe.

The gradual easing of tensions

But things have started to change. Several factors have contributed to gradually defusing this liturgical conflict. The motu proprio Summorum Pontificum of Benedict XVI in 2007 played a decisive role. By liberalizing the celebration of the extraordinary form of the Roman rite, the pope It normalized what was perceived as a marginal practice. The message was clear: one can be fully Catholic, in communion with Rome, and prefer the Latin Mass.

This official recognition has allowed many faithful to discover or rediscover the traditional liturgy without feeling they were joining a dissenting group. Diocesan priests have been trained to celebrate this liturgical form. Parishes have offered a monthly or weekly Tridentine Mass, creating bridges between the two rites.

At the same time, a new generation has arrived. These young Catholics, born in the 1990s or 2000s, did not experience the post-conciliar conflicts. For them, Vatican It belongs to ancient history, almost as much as the Council of Trent. They approach the liturgical question with a disarming pragmatism: what form of mass best nourishes my faith at the present moment?

Numbers that speak for themselves

Data from the Ifop study conducted for Bayard and La Croix confirms this trend. Approximately two-thirds of practicing Catholics no longer express opposition to the Latin Mass. This figure marks a turning point. It does not mean that all these Catholics regularly attend the Extraordinary Form, but rather that they no longer perceive it as problematic or suspect.

This acceptance transcends generations and sensibilities. There are, of course, young people, often curious to discover different liturgical forms. But also older Catholics who have lived Vatican They, in retrospect, adopt a less categorical position. The time for mutual excommunications is over; now is the time for peaceful coexistence, or even complementarity.

This standardization is not without debate. pope François took more restrictive measures in 2021 with the motu proprio Traditionalis custodes, limiting the celebration of the extraordinary form. A decision that sparked tensions but, paradoxically, did not prevent the continuation of the underlying movement: the progressive de-ideologization of the liturgical question.

Catholic youth in search of liturgical diversity

The profile of "bi-ritual" practitioners«

Who are these Catholics who navigate between the two liturgical forms? Their profiles are varied, but some commonalities emerge. Many belong to the 25-40 age group, often young couples with children. They grew up in a Catholicism that was already diverse, attending parishes with a distinct liturgical style during their childhood: charismatic, neo-catechumenal, or, conversely, more solemn.

Grégoire, our friend from Lyon whom we met in the introduction, perfectly embodies this dynamic. Married to a woman who appreciates the Tridentine Mass, he entered Saint-Georges with preconceived notions: "I was expecting a world of uptight, somewhat sectarian traditionalist Catholics." He was completely surprised. "I found large families, yes, but also young couples, students, recent converts. A real diversity, not at all the ghetto I imagined."«

What drew Grégoire to the Mass? First and foremost, the silence. «In the ordinary Mass, there’s always something: a hymn, a reading, a prayer. In the Extraordinary Form, silence has its place. The priest prays certain parts of the canon in a low voice. It helps me to collect myself, to let the prayer sink into me.» But he doesn’t abandon his usual parish altogether: «On Sundays, depending on how I feel, I need one or the other. Sometimes to sing in French with the whole congregation, sometimes this contemplative silence.»

What is so appealing about the extraordinary form

The reasons for discovering the Tridentine Mass are many. For some, it is primarily an aesthetic experience. The beauty of the vestments, the solemnity of the gestures, and the Gregorian chant create an atmosphere that fosters a sense of the sacred. In an age saturated with noise and images, this liturgy offers a striking contrast.

Sophie, 28, a lawyer in Paris, began attending the Extraordinary Form occasionally three years ago. "I discovered it out of curiosity, while accompanying a friend. I was struck by the eastward orientation, the priest and the faithful facing the same direction. It made me understand something: we are not celebrating for ourselves but for God. This vertical, transcendent dimension, I had been searching for it without knowing it."«

For others, it's a question of spiritual formation. The highly codified structure of the Tridentine Mass, with its many symbolic gestures and age-old prayers, offers catechesis in action. "When you see the priest wash his hands after the offertory, when you observe the three signs of the cross at the moment of consecration, you start to ask yourself questions. It prompted me to find out more, to better understand what happens at Mass," explains Thomas, 32, an engineer.

And what remains precious in the ordinary rite

But these same faithful do not renounce the ordinary Mass, far from it. They find other complementary riches in it. First, the active participation of the congregation. Singing in French, responding clearly to the liturgical dialogues, immediately understanding the readings: all these elements create a sense of community belonging.

«At ordinary Mass, I feel more involved,» Sophie confides. «The readings in French speak directly to me. The homily is more accessible. And I love singing with my neighbors, feeling that we truly form one body, the Church.» This horizontal, communal dimension complements the vertical dimension emphasized by the extraordinary form.

For many of these dual-ritual worshippers, it's not about ranking them but about drawing from two complementary traditions. One emphasizes mystery, the sacred, and transcendence. The other emphasizes participation, understanding, and fraternal connection. "Why choose when you can have both?" Grégoire sums up with a smile.

Smooth traffic flow between parishes

This dual ritual practice is accompanied by a new mobility. These Catholics readily attend several parishes according to their spiritual needs. On Sunday mornings, they might attend the 9 a.m. Mass in their local parish, then go the following Sunday to a Tridentine Mass in another church in the city. Major liturgical feasts become opportunities to discover different forms of celebration.

This kind of interaction was unthinkable just twenty years ago. The "traditionalists" kept to themselves, as did the "conciliarists." Today, the boundaries are porous. At Saint-Georges, you'll find parishioners who also attend Mass at Saint-Bonaventure, known for its excellent polyphonic singing in French. At Saint-Eugène-Sainte-Cécile, a Parisian parish renowned for its Extraordinary Form of the Mass, you'll encounter regulars who also go to Saint-Gervais for the liturgy of the Monastic Fraternities of Jerusalem.

This fluidity sometimes destabilizes established structures. Parish priests see their young parishioners leave on some Sundays to attend a Tridentine Mass. But many have understood that this is not a defection but a legitimate spiritual quest. "At first, I admit it hurt me a little," confides a priest from Lyon. "Then I realized that these young people weren't leaving because my Mass was bad, but because they were looking for something more. And ultimately, they come back, enriched by this diversity."«

Dual ritual, a new normal for the faithful

Moving beyond labels and oppositions

This practice of bi-ritual celebration helps to break down the stereotypes associated with the two liturgical forms. The Tridentine Mass is no longer the preserve of fundamentalist Catholics dreaming of a return to medieval Christianity. It now includes young urban professionals, artists, intellectuals, and converts from atheist backgrounds. The sociological diversity is real, even if certain profiles remain overrepresented (large families, professionals).

Conversely, the ordinary Mass is no longer perceived as the exclusive domain of progressive Catholics. Faithful faithful deeply attached to the Church's traditional doctrine happily attend when it is celebrated with care and reverence. The essential thing, they say, is not the language or the priest's orientation, but the spiritual quality of the celebration.

«"We have moved beyond this binary logic where liturgical choice automatically determined your positions on all subjects," analysis Married, 35 years old, teacher. "I know people who go to the extraordinary fitness center and who are very socially involved, in welcoming the migrants For example. And very charismatic regular churchgoers who hold very traditional moral views. The categories are exploding.»

A complementarity that enriches faith

For many of these bi-ritual Catholics, attending both liturgical forms becomes a true school of spirituality. Each offers different perspectives on the same Eucharistic mystery. Moving from one to the other allows them to rediscover dimensions that are sometimes forgotten.

«When I return to the ordinary Mass after several Sundays in the extraordinary form, I appreciate the clarity of the readings and the ease of following along in a different way,» Thomas testifies. «And conversely, after months of Mass in French, returning to the traditional form allows me to rediscover the meaning of the sacred and the importance of silence.»

This complementarity extends beyond Sunday Mass. Many of these faithful incorporate into their personal prayer elements drawn from both traditions. The Vespers service in French in the evening, the rosary In Latin, the lectio divina In a modern translation, the recitation of the psalms according to the old Vulgate numbering: everything is mixed together in a spiritual practice composite and coherent.

The pastoral challenges of this evolution

This dual ritual practice nevertheless raises concrete pastoral questions. How can we accompany these faithful who move between several parishes? How can we prevent them from becoming mere "consumers" of liturgies, flitting from one to another without truly committing to a community?

The question of parish involvement is indeed a concern. Some priests worry about parishioners who come to Mass but never participate in other parish activities, don't make themselves known, and don't get involved. "Mass isn't a spectacle to be consumed," one priest reminds us. "It integrates us into a real community, with its joys and its burdens."«

But others pastors They are adopting a more flexible vision. "These young people are telling us something important about their relationship with the Church," says a vicar general. "They no longer want to be confined to a single model. They are searching for what gives them spiritual life. It is up to us to accompany them in this quest, not to impose our rigid frameworks on them."«

The formation of priests presents another challenge. Few seminarians today are trained in both rites. Yet, to minister to these bi-rite faithful, priests themselves need to know and appreciate both liturgical forms. Some dioceses are beginning to offer training sessions in the Extraordinary Form, even without the intention of celebrating it systematically. The goal: to understand its spiritual significance.

Towards a Renewed Catholicism

Ultimately, this dual ritualism perhaps expresses a profound aspiration: that of catholicity in its fullest sense, that is, universality. The Catholic Church has always been diverse in its liturgical expressions. The Roman Rite coexists with the Byzantine Rite, the Maronite Rite, the Ambrosian Rite, and so many others. This richness is part of its very DNA.

«I feel more Catholic since discovering this liturgical diversity,» confides Grégoire. «I understood that the unity of the Church does not mean uniformity. We can pray differently while still sharing the same faith, the same Christ present in the Eucharist. »

This rediscovery of diversity within unity could have effects that extend beyond purely liturgical matters. It teaches us to hold together different sensibilities, to avoid demonizing those who pray differently. In a French society marked by divisions, this ability to engage with difference without abandoning one's convictions could be a valuable example.

The future is uncertain but promising

The future of this dual rite remains uncertain. The restrictions imposed by Rome in 2021 could limit access to the Extraordinary Form and hinder this momentum. Some bishops are strictly applying these directives, while others are more flexible. The coming years will tell whether this fundamental movement can withstand institutional obstacles.

But one thing seems certain: the rising generation will not resume the liturgical battles of their elders. For these young Catholics, the question "Ordinary Form or Extraordinary Form?" no longer holds much meaning. Their spontaneous answer would be more likely: "Both, depending on the moments in my spiritual life."«

This pragmatic approach, free from the ideologies that have long poisoned liturgical debate, could open up new perspectives. What if the real question were not so much the form of the rite as the spiritual quality of its celebration? What if, beyond languages and orientations, the essential element lay in this encounter with Christ who gives himself in the Eucharist, whatever the liturgical form?

The phenomenon of bi-ritual attendance reflects a profound evolution within French Catholicism. Far removed from the conflicts of the past, a new generation is forging its own path with pragmatism and spiritual thirst. By moving freely between Ordinary and Tridentine Masses, these faithful are not betraying fickleness but rather expressing maturity: the ability to draw upon the multifaceted richness of Catholic tradition to nourish their faith daily. This normalization of liturgical diversity, if it continues, could well foreshadow a more peaceful Catholicism, where the question is no longer "Which Mass should I attend?" but "How can I fully experience the mystery being celebrated?"«