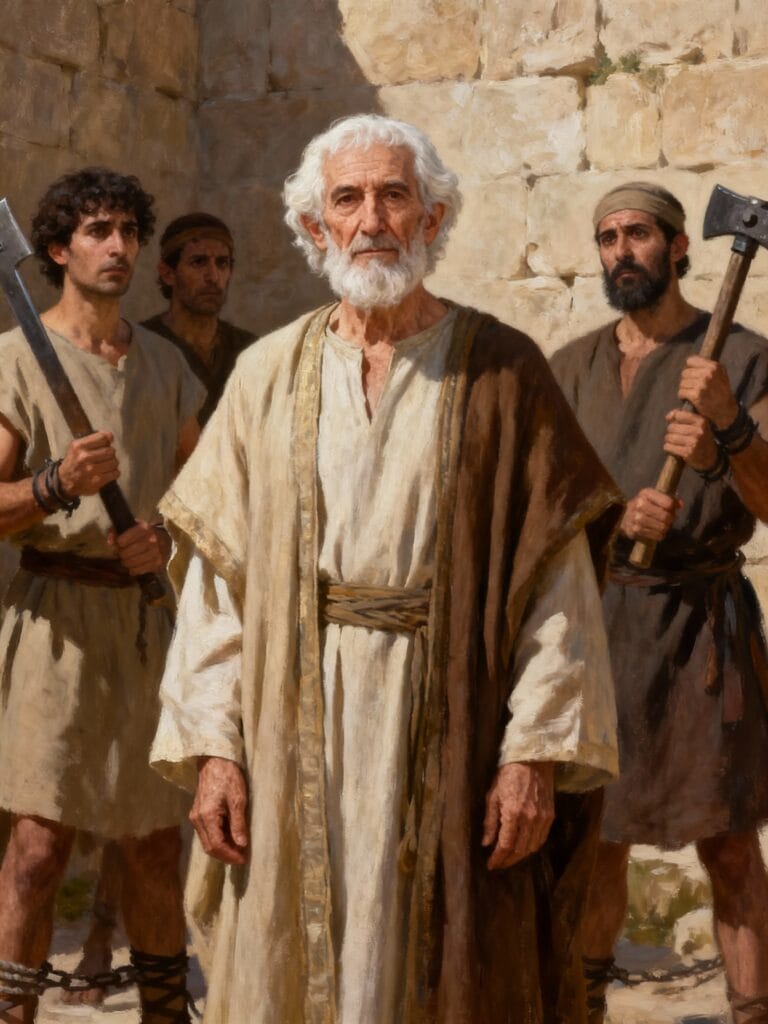

Reading from the second book of the Martyrs of Israel

In those days, Eleazar was one of the most distinguished scribes. He was a very old man, with a noble countenance. They tried to force him to eat pork by forcing his mouth open. Preferring a glorious death to an infamous life, he walked willingly toward the instrument of torture, after spitting out the meat, as anyone who has the courage to refuse what is forbidden to consume, even out of attachment to life, should do.

Those in charge of this unholy meal had known him for a long time. They took him aside and suggested he have some permissible meats brought in, which he would prepare himself. He would only have to pretend to eat the victim's flesh to obey the king; by doing so, he would escape death and be treated kindly thanks to his long-standing friendship with them.

But he reasoned with a noble spirit, befitting his age, the rank conferred upon him by his old age, the respect his white hair commanded, his irreproachable conduct since childhood, and above all, the holy law established by God. He spoke accordingly, requesting to be sent without delay to the realm of the dead: «Such a farce is beneath my years. For many young men would believe that Eleazar, at ninety, is adopting the lifestyle of foreigners. Because of this farce, through my fault, they too would be led astray; and I, for a miserable remainder of life, would bring shame and disgrace upon my old age. Even if I avoid, for the moment, the punishment that comes from men, I will not escape, living or dead, the hands of the Almighty.» "Therefore, by bravely departing this life today, I will prove myself worthy of my old age, and by choosing to die with resolve and nobility for our venerable and holy laws, I will have left to young people the noble example of a beautiful death." With these words, he walked straight to his execution.

To those who were leading him, these words were madness; therefore, they suddenly changed from kindness to hostility. As for him, at the moment of his death under the blows, he groaned: «The Lord, in his holy knowledge, sees it clearly: though I could have escaped death, I endure under the lash sufferings that torture my body; but in my soul I bear them with joy, because I fear God.»

Such was the end of this man. He thus left, not only to the youth but to his entire people, a model of nobility and a monument to virtue.

Dear reader,

Let me ask you a simple question, but one that I believe resonates with particular force today: what is integrity? In a world that seems to celebrate the art of compromise, of compromise, of "not making waves," what does it mean to "stand firm"? We all, to varying degrees, face situations where we are asked, politely or not, to "play along." To preserve a relationship, to keep a job, to avoid conflict. We are told it's "maturity," "flexibility.".

And then there's Eleazar.

Its story, nestled in the Second Book of Maccabees, The film is breathtakingly violent and clear. A 90-year-old man, a respected scholar, is ordered to do one simple thing: publicly eat pork to save his life. Something forbidden by his law, his faith, his very being. Worse, his friends, the very ones who should be supporting him, offer him a "humane" way out: "Pretend. Bring your own meat and act as if you're eating theirs. No one will know. You'll be saved."«

It is here, my friend, that the story of Eleazar ceases to be a dusty relic and becomes a mirror held up to our own conscience. His refusal is not an old man's whim, nor a narrow fundamentalism. It is a "beautiful argument," an act of existential clarity that proclaims that some things are more precious than life itself: truth, consistency, and the responsibility we have toward those who observe us.

The story of Eleazar is not the story of a man who chooses death; it is the story of a man who refuses a life that would be a lie. It forces us to ask ourselves: what is the "pork" that the world asks us to consume today? And what "comedy" do we refuse to play, out of love for the truth?

I invite you on a journey. A journey to the heart of the Hellenistic crisis, to understand the pressure exerted on this man. We will then delve into the purity of his "beautiful reasoning," this fortress of conscience. We will see how his choice, far from being an isolated act, was a radical act of teaching, a pillar for youth, and a foreshadowing of hope in the resurrection. Finally, we will explore together how the nobility of this ancient scribe can, even today, inspire and shape our own lives.

Prepare yourself. This is not a comfortable read. It is an encounter with the absolute.

📜 The tragedy of Antioch: a context of unwavering loyalty

To grasp the significance of Eleazar's act, we must shed our modern preconceptions. We read this text with the distance of 2,000 years, in a world where food choices are often a matter of personal preference, health, or individual ethics. For second-century BCE Israel, it was a matter of life or death, of identity and cosmic survival.

We are around 167 BC. Judea is no longer an independent kingdom. It is a province of the vast Seleucid Empire, one of the fragments of Alexander the Great's disintegrated empire. At its head reigns a man with a programmatic name: Antiochus IV Epiphanes. "Epiphane" means "the manifest god." This man is not content with merely ruling; he considers himself an incarnation of the divine, or at least its supreme representative on earth. His project is not only political or military; it is cultural. It is Hellenization.

Hellenism, Greek culture, was at the time what globalization can be today: a powerful, seductive wave that promised progress, philosophy, art, sport (the gymnasium), and a common language. Many Jews, especially the Jerusalem elite, were captivated. They saw Hellenism as a gateway to modernity.

But Antiochus was not a promoter of cultural exchange. He was an ideologue. To unify his fragile empire, threatened by Rome in the west and the Parthians in the east, he needed a single culture, a single religion. And Jewish particularism, with its single, invisible God and its strange laws (Sabbath, circumcision, dietary restrictions), was an affront to his project of unity.

The persecution that then descended upon Judea was unprecedented in its brutality and nature. It was not simply political oppression. It was the first documented religious persecution in history. Antiochus did not merely want the Jews' money or obedience; he wanted their soul.

He forbids the practice of the Law, the Torah. Possessing a scroll of Scripture became a capital crime. Circumcision, the sign of the Covenant in the flesh, was punishable by death (mothers who had their children circumcised were thrown from the city walls with them). The Sabbath rest was abolished. And the ultimate horror: the Temple in Jerusalem, the place of the unique presence of the Living God, was desecrated. A statue of Zeus Olympios was erected there, and pigs were sacrificed on the altar of burnt offerings. This was "the abomination of desolation.".

This is the world in which Eleazar lives. A world where being faithful is not just "going to the synagogue"; it's risking your life every day.

The text presents him to us with an almost cinematic solemnity. «Eleazar was one of the most eminent scribes.» A scribe, at that time, was not a mere copyist. He was a doctor of the Law, a theologian, a jurist, a judge. He was the intellectual and spiritual backbone of the people. «He was a very old man… and very handsome.» The author emphasizes this. He is 90 years old. He is not a youthful exuberance, a desperado seeking glory in martyrdom. He is the embodiment of Wisdom, of gravitas. His "fine appearance" is not only physical; it is moral. East the dignity of the Law.

And it is this man that the authorities choose to target. Why? Because if he gives in, him, The eminent scribe, the living symbol of tradition, will then all give in. His downfall will signal that resistance is futile.

The test is simple and diabolically symbolic: "They tried to force him to eat pork." Pork. The quintessential unclean animal, according to Leviticus. Eating it is not "just eating a piece of meat." It is a public act of repudiation of the Covenant. It is publicly declaring: "My Law is false, my God is powerless, and I submit to the new order of Antiochus-Zeus."«

It is a "sacrilegious meal." The scene is an inverted ritual. An anti-sacrifice. Instead of offering oneself to God, one submits to the idol. And Eleazar's reaction is immediate, instinctive, even before any reasoning: he "walked of his own free will towards the instrument of torture, after having spat out this meat.".

There is no deliberation. Faced with the abject, the only response is rejection. He chooses a "prestigious death" (a kalos thanatos, a "beautiful death" (ironically, a very Greek concept) rather than an "abject life." The scene is set. The choice is not between life and death. The choice is between two qualities of life: a faithful life that includes death, or a life of mere survival that is already a spiritual death.

💡 The "beautiful reasoning": analysis of a sovereign consciousness

It is then, dear reader, that the story reaches its dramatic and psychological climax. Faced with this public rejection, the authorities change tactics. Brute force has failed. Let's try seduction, "false benevolence.".

«Those who were in charge of this sacrilegious meal… took him aside.» Temptation always occurs in private. Sin seeks the shadows. Compromise hates witnesses. And what do they offer him? They invoke their «old friendship.» This is the most perverse temptation: the one that uses the bonds of affection to corrupt.

Their proposal is so reasonable. «Listen, Eleazar, we like you. We respect you. We don’t want you dead. We’re just asking you to ‘pretend’ (dokein (in Greek, which gave us "Docetism"). Pretend to obey. Bring your own meat, kosher if you like, and eat it. Everyone will think you're eating the king's offering. You'll be saved, we won't have to kill you, and everything will be back to normal.«

It's brilliant. It's the temptation of "acting." The temptation to separate the outward act from the inner conviction. The temptation to tell oneself: "God knows perfectly well what I think in my heart. This outward gesture is unimportant."«

And it is here that Eleazar delivers his "beautiful argument." An argument that stands as a monument to human and theological integrity. He does not respond with a cry of fanatical faith. He responds with a logic Relentless. Let's break it down, because it is our compass.

Personal consistency, the indignity of comedy (v. 24)

«"Such a comedy is beneath my age." The first reason is dignity. Not pride, but the consistency. He is 90 years old. He has spent nearly a century teaching the Law, living by the Law. His "white hair" is not merely a sign of old age; it is the symbol of a life lived in righteousness.

How could he, on the threshold of eternity, deny all that he had been? How could his life end in a lie, a farce? He must, to himself, to die as he lived. His life and death must form a coherent whole. He refuses to let his biography end with a shameful footnote. It is the refusal of the actor, the refusal of the hypocrite (in Greek, hypocrites (meaning "theatre actor"). He refuses to wear a mask.

Pastoral responsibility: setting an example for young people (vv. 25-27)

This is the heart of his reasoning, and it's devastating. Eleazar isn't (only) thinking about himself. He's thinking to the others. "Because many young people would believe that Eleazar, at 90 years old, is adopting the lifestyle of foreigners. Because of this charade, through my fault, they too would be led astray."«

That's the point. His life isn't his private property. As an "eminent scribe," he's a beacon. And if the beacon sends a false signal, ships run aground. He understands what we so often forget: our lives are lessons. Our choices, even the most intimate, have a public impact.

If he is "pretending," what will the young people say? They will say: "Look! Even Eleazar, the greatest among us, has given in. He understood that faith is good, but life is better. He understood that our traditions are not worth dying for. So why should we resist?"«

His compromise, even if simulated, would be a treason of the next generation. He prefers to die For them than to live against them. He refuses to be a Skandalon, a stumbling block on their path of faith. He chooses to be a «noble example» (v. 28), a «memorial of virtue» (v. 31). His death is not a failure; it is a pedagogical act. It is his final, most masterful lesson. He teaches that loyalty God is worth more than "a few miserable remnants of life".

The theological perspective: the inevitability of judgment (v. 26)

Finally, the ultimate argument. The vertical argument. "Even if I avoid, for the moment, the punishment that comes from men, I will not escape, living or dead, the hands of the Almighty."«

Eleazar places the scene on a larger stage. Antiochus's tribunal is merely a court of first instance. There is a Supreme Court, that of the Almighty God. And the verdict of this Court is the only one that matters.

Note the incredible phrase: "living or dead." It's a theological bombshell. At that time, the idea of a clear retribution after death, of a resurrection or personal judgment, was still developing in Israel. The prevailing thought (that of the future Sadducees) was that everything was decided here on earth. But the persecution strength the Revelation to be explored in greater depth.

Eleazar (and the author of 2 Maccabees) lays a crucial groundwork: if God is just, and if the righteous die For He, without being rewarded on earth, then the justice of God must to be exercised beyond death. Otherwise, God would not be just. Death cannot be an escape, neither for the wicked nor for the righteous. God is the God of the living. And deaths.

He therefore chooses his "fear." He has the choice between fearing Antiochus, who can kill the body, and fearing God, who holds both soul and body (as Jesus would say a century and a half later). He chooses the "fear" (loving respect, reverence) of God.

His "beautiful reasoning" is therefore the perfect fusion of personal dignity, social responsibility, and loyalty theological. He is not a fanatic. He is the most healthily, the most nobly rational man on the whole scene.

🏛️ Pillars of Faithfulness: The Three Pillars of Eleazar's Testimony

Eleazar's "beautiful reasoning" is not a mere intellectual abstraction. It is rooted in three profound realities that structure his entire being and his testimony. These three pillars are the Law, the Community, and a new Hope. Let us explore them, for they are the same pillars that can support our own integrity.

The Law as a way of life, not as a burden

For us, the word "law" often has a negative connotation: constraint, burden, limitation of freedom. We live in a culture that sees freedom as the absence of rules. For Eleazar, it's the exact opposite.

The Law – the Torah – is not a catalogue of arbitrary prohibitions. It is the gift from God to his people. It's the instruction manual for "choosing life," as it says Deuteronomy (Deut 30:19). The Law is the Wisdom of God offered to men so that they may live in harmony with Him, with others, and with creation.

The "venerable and holy laws" (v. 28) that Eleazar defends are not chains; they are the structure even of his identity and his freedom. Why the dietary laws? Because they are a constant reminder, three times a day, that the Jew is not like other nations. He is not "better," but he is "set apart" (kadosh, saint) for a mission: to be a witness to the one God in a polytheistic world.

Eating pork, therefore, is not simply breaking a rule. It is breaking the relationship. It is saying: "I no longer want to be 'set apart'. I want to be like everyone else. I want to dissolve into the great Hellenistic culture." It is an act of apostasy.

By refusing, Eleazar proclaims that the Law is a way of life, even and Above all when it leads to physical death. This is the ultimate paradox of faith. By obeying the Law unto death, he chooses the real life, the life of the Covenant, life in God. He tells the world that the identity given by God (being a member of his people) is more fundamental than biological existence.

This adherence to the letter of the law is not legalism. It is the visible sign of loyalty invisible to the Spirit of the Lawgiver. When the king attacks the sign (the food), Eleazar defends the signified reality (the sovereignty of God). He foreshadows, in a certain way, the attitude of Jesus. Although Jesus relativizes the laws of dietary purity (Mark 7:19), he does so not to abolish the Law, but to fulfill it (Mt 5, 17) by bringing back to his heart: the love of God and neighbor. Eleazar, by loving God more than his own life and by loving "youth" more than his own comfort, is already, without knowing it, at the heart of this new Law.

Martyrdom as a pedagogical and social act

The second pillar is community. Eleazar's choice is not an individualistic act of personal salvation. It is, through and through, an act social And pastoral.

The word "martyr" (in Greek, martus) does not mean "victim" or "hero." It means "witness." A witness is someone who speaks of what they have seen and what they know. Eleazar, through his death, bears witness. But to whom? "To the young men," and "to all his people" (v. 31).

He is the Father (Abba) of the nation at that precise moment. Like a father who, seeing his house collapsing, throws himself upon his children to protect them with his own body, Eleazar protects the faith of the next generation with his own body. He absorbs the tyrant's violence so that the faith of the young will not be crushed.

This is a vision of responsibility that we sorely lack. We tend to think, "My choices are my choices. I am free. What I do in private is my own business." Eleazar shouts at us, "Lies!" Everything you do is a lesson. You are always An "example" can be either a "noble example" or an example of cowardice. There is no neutral ground.

By choosing torture, he bought He gives his time and courage to others. His unwavering "no" is a bulwark. He shows that resistance is possible. He shows that the oppressor does not have the last word. He shows that a 90-year-old man, alone and unarmed, can be stronger than the entire Seleucid Empire, because he stands on the side of Truth.

This "beautiful death" is a seed. The author of 2 Maccabees knows this. In writing this story, he accomplished Eleazar's vow: he makes his death a "memorial of virtue." And this story, by inflaming the hearts of readers (like the Maccabean brothers who will take to the hills, or the seven brothers in the following chapter), will produce fruits of resistance and loyalty.

His blood literally becomes "seed of believers." He dies so that the people may live. He is a prophetic figure, a ram which opens a breach in the wall of fear. He does not die in vain ; he dies For the future.

The invisible stronger than the visible: The birth of hope

The third pillar is the most revolutionary. It is the hope in the afterlife, which arises from the absurdity of the suffering of the righteous.

Let us reread verse 30, undoubtedly the most profound: «At the moment of dying under the blows, he groaned, ‘The Lord, in his holy knowledge, sees it clearly: although I could have escaped death, I endure under the lash pains that make my body suffer; but in my soul I bear them with joy, because I fear God.'»

It's a passage of insane theological density.

First, the lament: "he said, groaning." This isn't some stoic superhero who feels nothing. The pain is real. The whip tears at his flesh. Faith isn't anesthesia. It doesn't take away suffering, it gives it meaning.

Next, the lucidity «The Lord… sees it clearly.» He is not alone in his torment. The «God of holy science» (a rare expression) is a witness to his innocence. He calls upon God as a witness against the injustice of men.

Then, the paradox «…my body… but in my soul…» Eleazar experiences a dissociation that only martyrdom can offer. His body is broken, but his soul—his deepest «self,» his consciousness, his identity—is not only intact, but it is in the joy.

Joy What joy! Joy of the consistency. Joy of someone who is perfectly aligned with what he believes. Joy to know that he did not betray, that he remained faithful to the Divine Friend. That is joy that nothing can take away, not even death, because it is joy of God in him.

This joy is the fruit of his "fear of God." It is not the fear of a slave, but the wonder of a lover. He loves God to such an extent that joy Being faithful to this love surpasses the pain of being tortured.

This experience is the existential foundation of faith in the resurrection. If a man can be simultaneously in physical agony and spiritual ecstasy, it proves that the spirit is stronger than matter. If God allows such a man to die, it means that death is not the end. God must to Eleazar to return to him the body which he sacrificed out of loyalty.

The martyrdom of Eleazar (and that of the seven brothers in chapter 7, which will be even more explicit) strength Israel's theology took a giant leap forward. The resurrection is no longer a vague hope; it becomes a need of divine justice. Eleazar does not die because he believes in the resurrection ; it is more accurate to say that it is because Men like Eleazar die in this way, so do the people of Israel understand the truth of the resurrection.

His death is a prophecy fulfilled. He dies. towards a life that only God can give. He has "left life" (v. 27) to be "sent to the realm of the dead," but he knows that he will not escape "the hands of the Almighty" (v. 26). These hands that judge him are also the hands that will save him.

💬 The Voice of the Fathers: Eleazar in the Memory of the Church

The example of Eleazar did not remain confined to Jewish memory. When the young Christian Church, in turn, faced persecution from the Roman Empire, where did it find role models? Certainly, in Jesus, the ultimate Martyr. But also, and overwhelmingly, in the Maccabean martyrs.

For the Church Fathers, these Old Testament figures were "Christians before their time." They had demonstrated a faith and courage that foreshadowed Christ. Eleazar and the seven brothers are, in fact, the only "saints" of the Old Testament to have had a liturgical feast day in the West (August 1st) specifically as martyrs.

Saint Ambrose of Milan, In the 4th century, he dedicated a treatise (part of From Jacob and the blessed life) to praise their courage. For him, Eleazar is the model of the good "shepherd" and teacher. He admires his "beautiful reasoning" not as Stoic philosophy, but as wisdom inspired by the Spirit of God. He sees in the rejection of "comedy" an essential lesson for Christians tempted to "pretend" to escape persecution (the lapsi, (those who had failed).

Saint Augustine of Hippo goes even further. In his sermons for the Feast of the Maccabees, he marvels. How these men, who lived Before the coming of Christ, before the revelation of the Resurrection In Jesus, could they have had such hope? For Augustine, this is proof that God's grace was already at work. Eleazar did not merely defend a "law"; he defended the Truth (THE Veritas), who is none other than Christ himself, not yet revealed. His rejection of falsehood, his love for youth, his hope in God's justice, all this, for Augustine, is already an echo of the Gospel.

Saint Gregory of Nazianzus, In the East, they are celebrated as athletes of faith, whose steadfastness surpasses that of pagan heroes. He highlights the paradox: it is through loyalty to the Law Jewish that they have become role models universal For Christians.

Closer to our time, the figure of Eleazar has haunted all those who have faced totalitarianism. Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Eleazar, a German theologian who resisted Nazism, could have reflected on his experience. Faced with a regime that demanded the "comedy" of allegiance, that asked Christians to "pretend" that Nazi ideology was compatible with the Gospel, Eleazar's "no" resonates with terrible force. The rejection of "cheap grace," the choice of "costly grace" that commits one's life—it is the same struggle.

Church tradition has thus seen Eleazar as the patriarch of the martyrs. He is the old man who holds the gate of the arena, showing the thousands of Christian martyrs who will follow him (from Saint Blandina to Saint Maximilian Kolbe) how one dies: with dignity, out of love for others, and with a joy in the soul that executioners can neither understand nor take away.

🕊️ Integrity in everyday life: Meditating with the Scribe

My friend, the story of Eleazar may seem overwhelming. We are (probably) not destined to die under the whip for a dietary prohibition. But we are all called upon, every day, to reject the "comedy" and to choose integrity.

The martyrdom of Eleazar is not an unattainable ideal; it is a practical guide. Here are a few simple ways to let his "beautiful reasoning" permeate our lives.

- Identify my "sacred laws." Take a moment of silence. What are the 3 or 4 values, beliefs, or truths that are absolutely non-negotiable for you? (Ex: truth, compassion, Justice for the weak, loyalty (To God, radical honesty…). Write them down. They are your «holy laws».

- Identify the "friendship propositions." Think about your week. Where and by whom are you tempted to "pretend"? What "old friendship" (peer pressure, desire to please, fear of conflict) is pushing you to compromise? "It's just a little white lie," "Everyone does it," "Don't be so rigid"... Recognize the voice of "reasonable" temptation.

- Remember the "young people." Before making a morally ambiguous choice (even a minor one), ask yourself Eleazar's question: "Who is watching me?" Your children, your colleagues, your friends, or simply "your inner self." Will your choice be a "noble example" or a "stumbling block"? Are we building or destroying the community through our "act"?

- Practice "fine reasoning." When faced with a dilemma, don't just react emotionally. Reason. Take a sheet of paper and write down your "fine reasoning." "Such a charade (the silence, the exaggeration, the deception) is unworthy of… (my age, my faith, my position)." Clarify for yourself why you are standing firm.

- Seek the "joy of the soul." Learn to distinguish the suffering of the "body" from joy of the "soul." Holding fast to your values will cost you: ridicule, discomfort, perhaps a financial loss or a missed promotion. This is the "suffering of the body." But feel, at the same time, joy deep, peace of the soul to have remained faithful to yourself and to God. It is this joy that is the true treasure.

- Pray for the «fear of God.» Eleazar’s courage did not come from himself. It came from his «fear of God.» Let us ask for this grace: the grace to «fear» (to reverently love) God more than we fear the opinions of men, failure, or suffering. Let us ask for the strength not to «flee,» but to remain present «in the hands of the Almighty.».

✨ From Death to Life: The Testament of Eleazar

We have reached the end of our journey. As you will have gathered, the story of Eleazar is much more than an edifying tale. It is theology in action. It is a revolution of consciousness.

This 90-year-old man, by rejecting a mere "comedy," redefined true strength. Strength is not Antiochus with his armies and instruments of torture. Strength is a free conscience that says "No.".

Eleazar radically transforms the meaning of his own death. The executioners think of him take life; but it is he who gives it given. They think so. punish ; he makes one education. They think so.’humiliate ; he makes it a "beautiful death" (kalos thanatosThey think so.’annihilate ; he makes it an eternal «memorial of virtue».

He leaves us a profoundly moving testament: consistency is the name of holiness. Integrity is the highest form of love. Responsibility for others, especially the youngest, is absolute.

Eleazar's revolutionary call, which still resonates with us today, is not (primarily) a call to die, but a call to live. To live in full light. To reject duplicity, the "comedy" that poisons our relationships, our businesses, our churches, and our own hearts.

Today, the world offers us a thousand "sacrilegious" meats: hatred of the other disguised as opinion, lies disguised as marketing, cowardice disguised as prudence, greed disguised as ambition.

The question Eleazar poses to us, across the centuries, is simple: Are we going to "pretend"? Or are we, worthy of our age, our white hair (present or future), and our faith, going to choose to leave, ourselves, "the noble example" of a beautiful life?

May the "fine reasoning" of this eminent scribe become our daily bread.

📌 A practical example

Here are some concrete steps to anchor Eleazar's testimony in your life:

- Read it again in one go chapters 6 and 7 of 2 Maccabees to feel the powerful bond between the "teacher" Eleazar and his "students", the seven brothers.

- Conduct a "consistency review"« Tonight: list a moment during the day when you were tempted by "acting out" and a moment when you were honest.

- Identifying a "young person"« (spiritually or by age) that you influence, and pray to be a "noble example" to him this week.

- Choose a small "torture"« : giving up a comfort or habit out of loyalty to a value (e.g., refusing to participate in gossip).

- Dare to say a principled "no" this week, even if it creates discomfort, by explaining it with calm "beautiful reasoning".

- Meditate on verse 30 "I endure... pains... but in my soul I bear them with joy." Try to find this joy in an effort or a difficulty.

📚 To learn more (References)

For those who wish to delve deeper into the context and scope of this fundamental text:

- Primary Text (Bible): THE Second Book of Maccabees (especially chapters 6 and 7).

- Primary Text (Tradition): Saint Ambrose of Milan, On the Maccabees (included in his treatise On Jacob and the Happy Life).

- Primary Text (Tradition): Saint Augustine of Hippo, Sermons for the Feast of the Maccabees (especially Sermons 300 and 301).

- Historical Context: Édouard Will, Political history of the Hellenistic world (323-30 BC). A key reference for understanding the Seleucid crisis.

- Theological Analysis: Elias Bickerman, The God of the Maccabees: Studies on the Meaning and Origin of the Maccabean Revolt. A classic work on the nature of Antiochus' persecution.

- Biblical Commentary: The "Biblical Sources" collection (or an equivalent commentary) on The Books of Maccabees for a detailed verse-by-verse exegesis.

- Contemporary Spiritual Perspective: Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Resistance and submission. A masterful reflection on the cost of loyalty and the rejection of "comedy" in the face of totalitarian power.