A reading from the book of the prophet Isaiah

Comfort, comfort my people, says your God; speak tenderly to Jerusalem. Announce that her time of trial is over, that her sin is forgiven, that she has received from the Lord's hand double for all her sins.

A voice cries out: «In the wilderness prepare the way of the Lord; make straight in the desert a highway for our God. Every valley shall be raised up, and every mountain and hill made low; the uneven ground shall become level, and the rough places a spacious plain. Then the glory of the Lord shall be revealed, and all flesh shall see it together, for the mouth of the Lord has spoken.»

A voice says, «Proclaim!» And I say, «What shall I proclaim?» All people are like grass, and all their beauty is like the flower of the field: the grass withers and the flower fades when the breath of the Lord blows on it. Yes, the people are like grass: the grass withers and the flower fades, but the word of our God endures forever.

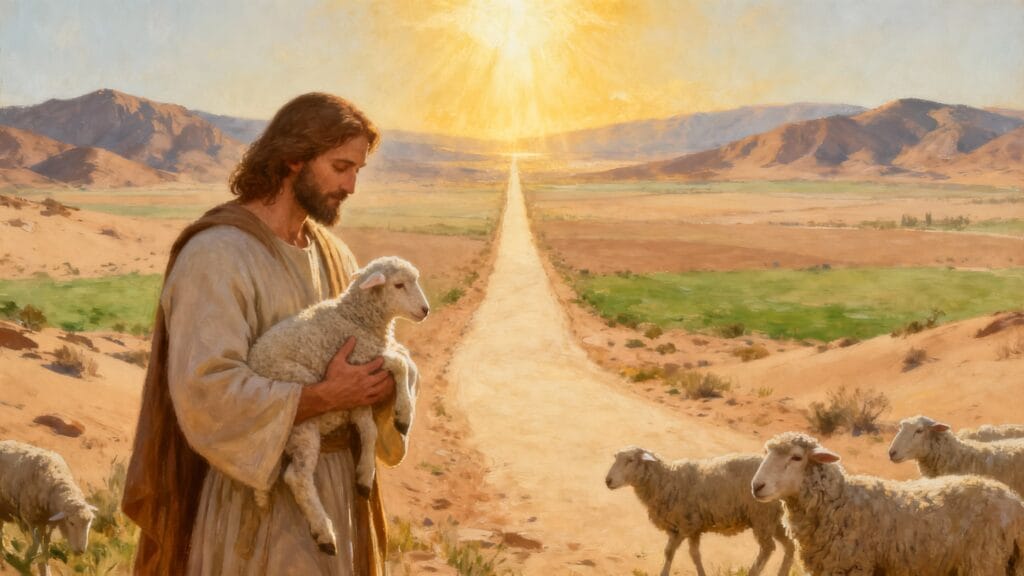

Go up on a high mountain, you who bring good news to Zion. Lift up your voice, you who bring good news to Jerusalem. Lift it up, do not be afraid. Say to the cities of Judah, «Here is your God!» Behold, the Lord God! He comes with power; his arm rules over all. Behold, his reward for his labor is with him, and his deeds before him. Like a shepherd, he leads his flock: his arm gathers the lambs, he carries them close to his heart, he gently leads those that are with young.

When God comforts his people: the promise of radical renewal

From the desert of exile to the road to freedom: how Isaiah 40 transforms our vision of God and reshapes our hope.

In moments of collective or personal desolation, we seek words that soothe without lying, that console without denying the hurt. The prophet Isaiah offers us precisely these words in chapter 40 of his book, a foundational text that opens the section known as the "Book of Consolation." This passage does not merely encourage a people broken by the Babylonian exile; it reveals a God who enters history to radically transform our condition. The dual image of the mighty God and the tender shepherd paints a divine face that responds to the deepest aspirations of humankind.

We will begin by exploring the historical and theological context of this text, then analyze its structure and central message. Next, we will delve into three essential dimensions: consolation as a creative act, preparation for the journey as communal conversion, and the tension between human fragility and divine permanence. We will conclude with a look at the Christian tradition and some concrete suggestions for meditation.

A text born of exile: when the people await their liberation

Chapter 40 of Isaiah marks a major literary and theological turning point in the prophetic book. We leave the world of the 8th-century BCE prophet to enter that of an anonymous 6th-century BCE prophet, whom tradition calls Deutero-Isaiah or Second Isaiah. This new voice rises in Babylon around 540 BCE, when the Jewish people had been living in forced exile for nearly fifty years.

The Babylonian exile represents far more than a simple geographical displacement. It is a total existential crisis: the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem, the end of the Davidic monarchy, the dispersion of the people, and the questioning of all religious certainties. How could one still believe in a God who had allowed the destruction of his own home? How could the identity of Israel be maintained far from the promised land? The Psalms of this period bear witness to this collective despair: «How can we sing the Lord’s song in a foreign land?»

In this context of desolation, the prophet receives a paradoxical mission: to announce consolation when nothing seems to justify hope. Yet, geopolitical history is beginning to shift. The Babylonian empire is faltering under the blows of Cyrus the Persian, who appears as a potential liberator. The prophet sees in these events the hand of God preparing the return of his people.

The text of’Isaiah 40 It functions like a symphonic overture. It announces all the themes that will be developed in the following chapters: the coming liberation, the new creation, the suffering servant, the restoration of Jerusalem. The divine voice that commands "Comfort, comfort my people" resounds like a decree of universal amnesty. The double imperative underscores the urgency and intensity of this consolation.

The structure of the passage reveals a dramatic progression. First, the divine declaration of total forgiveness: the crime is expiated, the punishment completed. Then, the mysterious call to prepare a way for God himself in the desert. Next, the striking contrast between the fragility of all flesh and the permanence of the divine Word. Finally, the triumphant announcement of God's coming, both a powerful conqueror and a caring shepherd.

This text belongs to the literary genre of the oracle of salvation, but it profoundly transforms it. Traditionally, the oracle of salvation responded to an individual or collective lament by assuring everyone that God had heard the prayer. Here, consolation even precedes the request. God takes the absolute initiative. He does not respond to a complaint; he anticipates the need and answers it abundantly.

The liturgical use of this passage in the Christian tradition testifies to its universal scope. It is read during Advent, This was a time of preparation for the coming of Christ. John the Baptist would be identified with this "voice crying out in the wilderness," making the Isaiah text a messianic prophecy. This Christological reading does not negate the text's primary meaning, but reveals its inexhaustible depth.

Divine consolation as an act of new creation

Analysis of the text reveals a revolutionary theology of consolation. The Hebrew word naham, To "console" does not simply mean emotional sympathy. It implies a change of inner disposition in the one who consoles, and by extension, a transformation of the situation of the one who is consoled. When God consoles, he does not merely soothe suffering: he creates a new reality.

The repetition of "comfort, comfort" functions as a poetic emphasis typical of biblical Hebrew. This duplication not only aims at insistence but also suggests the fullness and totality of the divine act. God consoles completely, definitively, and without reservation. The expression "speak to the heart" evokes the intimacy of a loving relationship. In the Bible, speaking to the heart means to seduce, to win back, to establish a new covenant. God courts his people as a husband reunites with his wife.

The proclamation that the service is completed and the crime atoned for introduces a theology of radical forgiveness. The word "service" translates the Hebrew tsaba, This term refers to both compulsory military service and forced labor. Exile was therefore not perceived as a mere ordeal, but as a sentence of servitude imposed for the people's transgressions. To declare that this sentence was over was tantamount to a general amnesty proclaimed by the sovereign himself.

Even more audacious: Jerusalem received «double for all her sins.» This expression has puzzled commentators. How could a just God punish doubly? The most coherent interpretation sees in this «double» not an excess of punishment, but an overabundance of consolation. God does not merely restore balance: he more than compensates for suffering with overflowing joy. This logic of divine abundance foreshadows the Pauline theology of grace, which abounds where sin has abounded.

The desert appears as the paradoxical setting for this new creation. Geographically, it is the Syro-Mesopotamian desert that the people must cross to return from Babylon to Jerusalem. Symbolically, the desert refers to the original Exodus, when Israel crossed Mount Sinai to reach the promised land. But here, the desert becomes the site of a new divine revelation, an unprecedented theophany.

The voice that commands the preparation of the path remains mysterious. Who is speaking? The text does not specify. This uncertainty creates a sense of universal urgency. It is as if all of creation were summoned to participate in this preparation. The imperatives follow one another: fill the ravines, lower the mountains, level the escarpments. These images evoke the great road projects of ancient empires, when the sovereign had triumphal roads built for his travels.

Yet here, it is God himself who travels, and the people who prepare for his arrival. The reversal is complete: it is no longer the people who walk toward God, but God who comes to his people. This theological inversion transforms our understanding of faith. We are not primarily seekers of God, but those found by God. Our task is not to reach the divine through our own efforts, but to prepare within ourselves the space to receive it.

Human fragility and divine permanence: the paradox of our condition

The text then presents a striking contrast between the ephemeral and the eternal. The voice commands the proclamation, and the prophet asks, «What shall I proclaim?» This hesitation is not disobedience, but a clear-sighted understanding of the human condition. How can one announce lasting good news to beings marked by mortality?

The answer comes in the form of a stark observation: "All flesh is like grass." The image of withering grass expresses universal vulnerability. In the climate of Middle East Ancient times have shown that grass is green for a few weeks in spring, then quickly dries out under the scorching desert wind. This metaphor applies to all living beings, without distinction. Kings and shepherds, powerful and humble, share the same fundamental fragility.

The "breath of the Lord" that dries the grass plays on the ambiguity of the Hebrew word. ruah, which signifies wind, breath, and spirit. What withers human existence is not ordinary time, but the passage of the divine, which reveals our inconsistency. Faced with the absolute transcendence of God, all human grandeur collapses. The Babylonian empires, which seemed eternal, are but chaff carried away by the wind.

This meditation on finitude could lead to nihilistic despair. But the prophet effects a decisive reversal: «The word of our God endures forever.» Permanence does not belong to humankind, but to the Word that constitutes and sustains it. Our hope does not rest on our capacity for resistance, but on loyalty of God to his promise.

This tension between fragility and permanence runs through all of human existence. We experience our vulnerability daily: aging bodies, failed projects, broken relationships, and wavering certainties. No worldly success can shield us from the passage of time. Stoic philosophies sought the solution in the serene acceptance of impermanence. Eastern wisdom traditions offer detachment as a path to liberation.

The biblical response takes a different path. It neither denies nor glorifies fragility. It fully acknowledges it, but situates it within a relationship with an Other who is eternal. Our finitude becomes bearable not because we transcend it, but because we are sustained by a Word that precedes us and will outlive us.

This Word does not float in some abstract heaven. It is embodied in a concrete history, that of a people and their promises. When the prophet affirms that the Word remains, he is thinking of God's commitments to Israel: the covenant with Abraham, the liberation from Egypt, the promise made to David. Despite exile and apparent destruction, these promises still hold true. God remains faithful even when all seems lost.

The announcement of the good news: Mission Impossible has become reality

The passage culminates in a scene of missionary dispatch. The prophet is ordered to ascend a high mountain to proclaim the good news. The Hebrew term translated as "to bring the good news" (mebasser) will give in Greek the word "gospel". We are witnessing the birth of a major theological concept: the announcement of a liberation that overturns the established order.

This good news is addressed first to Zion and Jerusalem, personified as women awaiting the return of their exiled children. But the message extends far beyond this initial context. It is a cry to all the cities of Judah: «Here is your God!» This exclamation resounds like a sudden epiphany. After decades of apparent absence, God manifests himself again, visible and active.

The portrait of God that follows juxtaposes two seemingly contradictory images. First, the Lord comes «with power,» his arm subduing all. The image is that of the victorious conqueror bringing back spoils of war and freed prisoners. The «fruit of his labor» and «his work» refer to the people themselves, snatched from Babylonian servitude like trophies of victory.

This theology of divine power addresses a profound anguish felt by the exiled people. How could they still believe in a God who had allowed his people to be crushed by the Babylonians? The prophet asserts that this apparent defeat actually concealed a divine strategy of purification. Now, God deploys his true power, not to destroy, but to liberate. He fights against oppression, not against his people.

But immediately, the image changes radically. This powerful God reveals himself "as a shepherd tending his flock." The figure of the shepherd evokes tenderness, closeness, and care for the most vulnerable. The shepherd knows each animal; he calls his sheep by name. He does not lead by brute force, but by a reassuring presence.

The detail, "his arm gathers the lambs, he carries them to his heart," pushes anthropomorphism to the point of emotion. The lambs, too young to follow the flock, are held against the shepherd's chest. This image of maternal tenderness applied to God masculinizes maternal instinct without diminishing it. God carries his people as a mother carries her child, close to the beating heart.

The special attention given to "the nursing ewes" reveals a God attentive to the most vulnerable. Mothers nursing their young cannot keep up with the pace of the flock. The shepherd adapts his pace to their capacity. This divine pedagogy of patience This contrasts with human impatience. We often want to force the pace of our spiritual growth. God, however, respects our fragility and progresses at our own pace.

This dual image of the warrior God and the shepherd God resolves a fundamental theological tension. How can God's absolute transcendence be reconciled with his closeness to every creature? How can his omnipotence be affirmed without denying his tenderness? The text refuses to choose between these attributes. It holds them together, revealing a God who is simultaneously above all and at the heart of all.

Consolation as community reconstruction

The text's scope extends far beyond the individual. Divine consolation is addressed to the "people," to Jerusalem, to the cities of Judah. It aims at restoring a social fabric torn apart by exile. This collective dimension of consolation deserves to be explored, for it sheds light on our own situation of social fragmentation.

The Babylonian exile shattered the communal structures of Israel. Families were scattered, networks of solidarity broken, and religious and political institutions destroyed. For fifty years, the people lived fragmented, each trying to survive as best they could in a hostile environment. Some succeeded economically, others sank into poverty. Some maintained their faith, others assimilated into Babylonian cults.

The return announced by Isaiah 40 It can only be a collective return. No one will reclaim their land unless everyone else does. No one will rebuild the Temple without everyone's participation. Divine consolation therefore implies a reconstruction of "us," a restoration of broken social bonds. God does not console isolated individuals; he remakes a people.

This prophetic intuition resonates with our contemporary situation of rampant individualism. We live in societies where everyone copes with their suffering in solitude, where depression becomes a private illness treated with pills. Traditional structures of solidarity have collapsed without being replaced. The extended family, the village, the parish, the union: all these places of mutual support have eroded.

The text of Isaiah suggests that true consolation can only be a communal act. Someone must "speak to the heart" of another, voices must rise to proclaim the good news, and messengers must ascend the mountain to shout that God is coming. Consolation is passed from mouth to ear, from heart to heart. It circulates within a living network of authentic relationships.

The image of the path to be prepared in the desert then takes on an ethical and social dimension. Filling in the ravines means reducing the inequalities that widen the gap between rich and poor. Lowering the mountains means dismantling the structures of pride and domination that prevent encounter. Leveling the escarpments means making institutions accessible to the most vulnerable.

This preparatory work is entrusted to the community itself. God does not impose his order by force. He waits for us to prepare the conditions for his coming. This divine pedagogy respects our freedom while empowering us. We cannot create salvation by our own strength, but we must create the space to receive it.

Proclaiming the good news then becomes an urgent collective task. In a world saturated with bad news, where the media daily bombard us with violence, disasters, and scandals, bearing the good news of a comforting God requires prophetic courage. We must dare to affirm that hope is possible, that reconciliation is realistic, that love can transform social structures.

This mission does not fall solely to religious specialists. The text is addressed to Zion itself, to Jerusalem personified: «You who bring the good news.» The wounded community itself becomes a messenger of consolation. Those who have endured exile are best placed to announce liberation. Those who have known despair can authentically speak of hope.

Echoes in the Christian tradition

The Church Fathers read Isaiah 40 as a direct prophecy of Christ. Origen sees in the voice crying out in the wilderness the preaching of John the Baptist preparing for the coming of the Messiah. The consolation promised to Israel finds its fulfillment in the Incarnation of the Word. The path to be prepared becomes the inner path of conversion of heart.

Augustine expands on this interpretation by showing how Christ embodies the dual image of conqueror and shepherd. Through his death and resurrection, he triumphs over sin and death, manifesting divine power. But through his earthly life, he reveals the tenderness of the shepherd who knows his sheep and lays down his life for them. The two dimensions are reconciled in the Pascal's mystery.

Medieval spirituality, particularly that of Bernard of Clairvaux, meditated at length on the image of God carrying lambs in his arms. This image nourished a whole mystical tradition of union with Christ in the intimacy of heart-to-heart communion. Divine consolation was no longer merely a future promise; it became a present experience in contemplative prayer.

John of the Cross It takes up the theme of the desert from Isaiah to describe the "dark night" of the soul. The external desert of exile becomes the inner desert of purification. But as in Isaiah, this desert is the place of a new encounter with God, more intimate and truer than any sensory consolation. The fragility of the withering grass illustrates the stripping away necessary to receive the enduring Word.

Contemporary theology, particularly in the work of Jürgen Moltmann, has revived the theme of Isaiah's prophetic hope. In a world marked by the Holocaust and totalitarian regimes, the promise of divine consolation takes on a new urgency. Moltmann shows how Christian hope does not flee from present suffering, but confronts it by drawing upon loyalty of God to his promises.

Christian liturgy has made of’Isaiah 40 a central text of the time Advent. Each year, the Church symbolically relives the waiting of Israel in exile, preparing for the coming of Christ not only in the memory of Bethlehem, but in the hope of his glorious return. The "prepare the way of the Lord" becomes an urgent call to personal and social conversion.

Integrate this message into daily life

Begin each day by embracing the phrase "Comfort, comfort" as a personally entrusted mission. Identify someone in your circle who is going through a difficult time and find a way to "speak to their heart" authentically, not with ready-made phrases but with genuine presence.

Practice the exercise of inner solitude by setting aside moments of radical silence, away from screens and noise. In this voluntary desert, prepare the way of the Lord by identifying the obstacles that clutter your inner life: resentments, fears, false securities.

Meditate on your own fragility without trying to deny or compensate for it. Contemplate how your life is like grass that flourishes and then withers. Embrace this finitude not as a curse but as a truth that makes you receptive to the enduring Word of God.

Take concrete action to "prepare the way" at the social level: join an initiative that bridges chasms of inequality, lowers mountains of injustice, and smooths out obstacles of exclusion. Translate the prophetic metaphor into a political and solidarity-based act.

Practice sharing the good news in your everyday conversations, not through clumsy proselytizing, but through a genuine testimony of hope. When the news is overwhelming, dare to name the signs of divine consolation that persist despite everything.

Cultivate the image of the tender shepherd by developing your capacity to care for the most vulnerable members of your community. Who are the lambs who need to be carried? Who are the ewes who are nursing and require a tailored pace? Adjust your presence to their vulnerability.

Create a weekly ritual of communal reflection where you share with others moments when you have experienced or offered divine comfort. This practice rebuilds the torn social fabric and concretely fulfills Isaiah's promise.

The radical call for an embodied hope

The text of’Isaiah 40 He does not leave us in peace. He rejects the comfort of an intimate spirituality that would be content with fleeting emotional consolations. He calls us to a radical transformation of our perspective on God, on ourselves, and on the world. Divine consolation is not a temporary balm for our wounds; it is a total re-creation of our reality.

The revolutionary power of the prophetic message lies in its ability to reconcile apparent opposites: power and tenderness, transcendence and closeness, divine initiative and human responsibility. God comes with strength, yet he carries the lambs close to his heart. He commands sovereignly, yet he respects the pace of the weakest. He forgives completely, yet he calls us to prepare his way.

Our contemporary world desperately needs this authentic word of consolation. We live in an age of widespread exile: exile from nature through urbanization, exile from traditions through accelerated modernity, exile from community ties through individualism. Like Israel in Babylon, we wander in an environment not made for us, nostalgic for a promised land we can barely imagine.

Isaiah's answer is neither to flee this world nor to passively accept it. It invites us to discern within it the signs of God's coming, to actively prepare his way. The desert of our modernity can become the place of a new encounter with the divine. Our collective frailties, far from condemning us to despair, make us open to a Word that never fades away.

The urgency of our time demands that we climb the high mountain to proclaim the good news. This proclamation can only be collective and committed. It takes shape in concrete acts of solidarity, in struggles for justice, in the patient building of alternative communities. It is proven in our capacity to truly comfort those who weep, to lift up those who have fallen, to support those who no longer have the strength to walk.

The God of’Isaiah 40 He precedes us on every path of exodus. He awaits us in the deserts where we lose our way. He carries on his heart our most unspeakable frailties. He adapts his steps to our hesitant pace. This divine faithfulness, stronger than all our inconsistencies, grounds an indestructible hope. It allows us to dare the impossible: to believe that consolation is real, that the path truly opens, that the glory of the Lord will be revealed to all flesh.

Practical

Morning ritual of consolation Before starting your day, repeat internally "God comforts me" for three minutes, breathing deeply, until this certainty permeates your being.

Exercise of the inner path : Identify each week a ravine to fill, a mountain to lower in your spiritual life, and take a concrete action of transformation.

Meditation on fragility : Once a week, contemplate a flower, grass or an ephemeral natural element while meditating on your own finitude in the face of divine permanence.

Good news announcement : Share daily with someone a word, a gesture or a message that authentically carries hope, however small, in an often dark news cycle.

Shepherd's practice : Choose a vulnerable person from your circle each month and adapt your presence to their pace and needs, without imposing your own.

Proofreading group Form or join a small group that meets monthly to share experiences of divine consolation lived and offered.

Solidarity commitment : Join a collective action that concretely prepares the way of the Lord by fighting against injustice or supporting the excluded of your society.

References

Book of the Prophet Isaiah, chapters 40 to 55, in particular Isaiah 40, 1-11 (foundational text studied in this article)

Psalm 23 on the Good Shepherd, Psalm 137 on the Babylonian exile, completing the understanding of the historical and theological context

Gospel according to Saint John, chapter 10, 1-18, on Christ the Good Shepherd fulfilling the prophetic figure

Origen, Commentary on Saint John, developing the patristic interpretation of the voice crying in the wilderness

Augustine of Hippo, Commentary on the Psalms, particularly on Psalm 22 (23), exploring the figure of the divine shepherd

Bernard of Clairvaux, Sermons on the Song of Songs, meditating on the intimacy of a heart-to-heart with God

John of the Cross, The Dark Night of the Soul, reinterpreting the desert as a place of purification and mystical encounter

Jürgen Moltmann, Theology of Hope, updating Isaiah's prophetic message for the contemporary world