Reading from the Book of Exodus

In those days,

Moses had heard the voice of the Lord

from the bush.

He answered God:

“So I will go to the children of Israel and say to them:

“The God of your fathers has sent me to you.”

They will ask me what his name is;

What shall I answer them?

God said to Moses:

“I am who I am.

Thus you shall speak to the children of Israel:

“He who sent me to you is I AM.”

God said again to Moses:

“Thus you shall speak to the children of Israel:

“He who sent me to you,

it is THE LORD,

the God of your fathers,

the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, the God of Jacob.”

This is my name forever,

It is through him that you will remember me from generation to generation.

Go, gather the elders of Israel together. Say to them:

“The Lord, the God of your fathers,

the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob,

appeared to me.

He told me:

I visited you and thus I saw

how you are treated in Egypt.

I said: I will make you go up

of the misery that overwhelms you in Egypt

to the land of the Canaanites, the Hittites,

of the Amorite, the Perizzite, the Hivite, and the Jebusite,

the land flowing with milk and honey.”

They will listen to your voice;

then you will go, with the elders of Israel,

to the king of Egypt, and you shall say to him:

“The Lord, the God of the Hebrews,

came to find us.

And now let us go

in the desert, three days' walk,

to offer a sacrifice to the Lord our God.”

Now I know that the king of Egypt will not let you go

if he is not forced to.

So I will stretch out my hand,

I will strike Egypt with all kinds of wonders

that I will accomplish in the midst of her.

After that, he will allow you to leave."

– Word of the Lord.

“I Am Who I Am”: Discovering the Name That Transforms Your Relationship with God

Exodus 3:14 reveals much more than a mysterious name: it is the invitation to meet the God eternally present, free and engaged in your personal story.

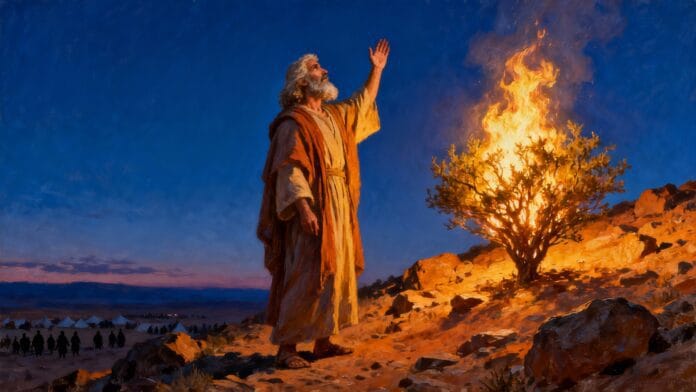

Imagine Moses, barefoot before a burning bush that does not consume itself, daring to ask God his identity. The answer he receives—“I am who I am”—has resonated for more than three millennia as one of the most enigmatic and powerful words in all of Scripture. This verse from Exodus 3:14 does not simply reveal one divine name among others: it opens a window onto the very nature of God, onto his absolute being, onto his unalterable presence. For any believer in search of spiritual depth, for anyone eager to understand who the God of the Bible truly is, this revelation constitutes an inexhaustible theological and existential treasure.

In this article, we will first explore the historical and spiritual context of this revelation at the burning bush, before analyzing the richness of the divine name "I am." We will then unfold three essential dimensions: the absolute transcendence of God, his liberating presence in human history, and his personal commitment to each person. We will forge links with the great Christian spiritual tradition, then propose concrete ways to make this revelation a living source of inner transformation.

Context

The Desert of Midian and the Burning Bush

The episode of the burning bush occurs at a decisive turning point in the history of Israel. Moses, who had fled Egypt forty years earlier after killing an Egyptian overseer, now leads a modest existence as a shepherd in the service of his father-in-law Jethro, a priest of Midian. The text takes us to Mount Horeb, also known as the mountain of God, in Sinai. It is there, in the solitude of the desert, that one of the most striking theophanies of the Old Testament takes place.

The story of Exodus 3 begins with a mysterious scene: a bush burns without being consumed. This paradoxical image captivates Moses and already symbolizes something of the divine nature: a power that manifests itself without being destroyed, a presence that acts without being exhausted. When Moses approaches, God calls his name and orders him to remove his sandals, for the place is holy. Ordinary earth becomes sacred space through the divine presence. God first presents himself as "the God of your father, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, the God of Jacob," thus establishing continuity with the patriarchs and the ancestral covenant.

But the stakes of this encounter go beyond the simple confirmation of a spiritual lineage. God reveals to Moses that he has seen the misery of his people in Egypt, that he has heard their cries under the blows of their oppressors. He declares that he has come down to deliver Israel and lead them to a land flowing with milk and honey. Moses is then chosen as the instrument of this liberation. Faced with this overwhelming mission, Moses asks a natural but far-reaching question: "Behold, I will go to the children of Israel and say to them: The God of your fathers has sent me to you. But if they ask me what his name is, what shall I tell them?"

The revelation of the Name

This is where the central revelation occurs. God answers Moses in Hebrew: "Ehyeh Asher Ehyeh," traditionally translated as "I am who I am." This enigmatic formula derives from the Hebrew verb "hayah," which means "to be," "to exist," "to become." The classic English translation, "I am who I am," suggests absolute being, self-existence, and eternal permanence. Other translations offer "I will be who I will be," emphasizing the dynamic and future dimension of the name, or "I am who I am," expressing divine self-determination.

This ambiguity is not a weakness of the text but its strength. The revealed name resists any reductive definition. God adds: "Thus you shall say to the children of Israel: I AM has sent me to you." Then he continues: "The Lord, the God of your fathers, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac and the God of Jacob, has sent me to you. This is my name forever, this is my memorial for all generations." The tetragrammaton YHWH, which Jewish tradition does not pronounce out of respect, is thus directly linked to this revelation of the "I AM."

This revelation does not occur in a temple, nor during a solemn ceremony, but in the desert, before a man who doubts his abilities. It inaugurates a new chapter in the relationship between God and his people, founded not on a visible and manipulable idol, but on a Name that expresses living presence and unwavering fidelity. In the Catholic liturgy, this passage is proclaimed during certain celebrations linked to vocation and mission, reminding believers that God calls each person by name and reveals himself in the intimacy of a personal encounter.

Analysis

The absolute being facing the nothingness of idols

The guiding idea of "I am that I am" lies in the affirmation of God's absolute being in the face of the ontological nothingness of idols. By revealing his name in this way, God establishes a radical distinction between himself and all the artificial deities that ancient peoples worshipped. The Egyptian, Babylonian, or Canaanite gods bore names linked to natural forces, geographical locations, or specific functions. But the God of Israel is defined by his very being, by his pure and unconditional existence.

This revelation contains a fertile paradox: on the one hand, it affirms that God IS, absolutely, without depending on anything or anyone; on the other, it refuses to reduce God to a fixed essence that human intelligence could grasp and confine within a definition. "I am that which I am" means both "I am Being itself, the source of all existence" and "I am what I choose to be for you, I do not allow myself to be confined within your categories." It is a revelation that simultaneously gives and steals, that illuminates and preserves the mystery.

Both Saint Augustine and Saint Thomas Aquinas meditated deeply on this verse. For Aquinas, Exodus 3:14 constitutes the scriptural foundation of his metaphysics of being. God is "Ipsum Esse Subsistens," the Self-subsisting Being, the One whose essence is to exist. All creatures receive being from God, but God IS being. This crucial distinction explains why God does not change, why he is eternal, why he is perfect: his being does not depend on any external cause; it is the very fullness of existence.

The existential scope of this revelation is immense. It means that God is not a human construct, a projection of our desires or our fears. He is not an abstract idea or an impersonal force. He IS, in the fullness and density of his being. This affirmation establishes the trust of the believer: he who relies on "I am" does not rely on sand but on the rock of being itself. When everything wavers, when human certainties collapse, when projects fail and hopes are shattered, the "I am" remains, unshakeable, the source of all stability and all hope.

The dynamics of presence and promise

The analysis of the divine name cannot be limited to a static metaphysics of being. The Hebrew "Ehyeh Asher Ehyeh" also allows the translation "I will be who I will be," opening up an essential temporal and dynamic dimension. God does not simply affirm his eternal existence outside of time; he commits himself to being present in time, in the concrete history of his people. The "I will be" expresses a promise: "I will be with you, I will be there when you need me, I will be faithful to my covenant."

This dynamic reading illuminates the entire context of revelation. Moses does not ask for a theological exposition of the divine nature, but rather practical assurance for his impossible mission: how to convince an enslaved people and an all-powerful pharaoh? God's response is not, "This is what I am in myself," but "I am with you, I will be present every step of the way, you can count on me." The divine name thus becomes a guarantee of active and liberating presence.

This dynamism of the "I am" runs through the entire history of salvation. God accompanies Israel in its exodus from Egypt, in the crossing of the Red Sea, in the desert, in the conquest of the promised land. To each generation, the name revealed at the burning bush reminds us that God is not only the distant creator who launched the world like an autonomous mechanism, but the close, engaged God, who intervenes to save and liberate. This proximity does not cancel his transcendence: God remains the Wholly Other, the Holy One before whom Moses veils his face. But this transcendence does not mean indifference; on the contrary, it signifies an infinite capacity for presence and action.

In the New Testament, Jesus takes up this formula of the “I am” in the Gospel of John, repeatedly affirming “Ego eimi” (“I am”), notably in John 8:58: “Before Abraham was, I am.” This statement provokes the indignation of the Pharisees because they understand that Jesus is identifying himself with the God of Exodus 3:14. The eternal “I am” became flesh, he entered our history, he pitched his tent among us. The incarnation thus becomes the ultimate extension of the revelation of the burning bush: God does not cease to be the absolute and transcendent “I am,” but he chooses to make himself present in the most intimate and vulnerable way possible.

The transcendence that frees from all idolatry

The revelation of "I am that I am" constitutes a radical liberation from idolatry in all its forms. In ancient Egypt, where Moses grew up, gods were everywhere: Ra the sun, Osiris the king of the dead, Apis the sacred bull, Horus the celestial falcon. Every natural force, every impressive animal, every cosmic phenomenon could become an object of worship. These deities were represented by statues that could be seen, touched, and carried around. They gave the illusion of control: sacrifices were offered to them to obtain their favors, and they were manipulated through magical rites.

The God who reveals himself to Moses breaks this logic. By refusing to give a descriptive or naturalistic name, by simply affirming "I am," he escapes all attempts at manipulation. He cannot be reduced to a function, locked away in a temple, or represented by an image. The second commandment of the Decalogue, received a few chapters later at Mount Sinai, will specifically prohibit the making of divine images. This prohibition is not arbitrary: it stems directly from the nature of the "I am." How can one represent being itself? How can one sculpt pure existence? How can one paint the one who is beyond all form?

This divine transcendence frees man from magical anxiety. In idolatrous religions, man lives in constant fear of offending the capricious gods, of missing a rite, of neglecting an offering. He becomes a slave to his own religious creations. The "I am" reverses this relationship: man does not have to invent God or control him, but to respond to his initiative, to welcome his presence, to trust in his fidelity. Religion becomes a dialogue with a personal God rather than a technique for manipulating the sacred.

This liberation from idolatry remains burningly relevant today. Our modern idols are no longer statues of stone or wood, but they are no less real: money, power, social success, self-image, technology, public opinion. We seek our security, our identity, our meaning in these realities which, like ancient idols, can neither see, nor hear, nor save. The "I am" of Exodus 3:14 resonates as a call to recognize the only true source of being and meaning. God alone truly IS; all else receives its being from him and returns to nothingness without him.

The tradition of the Fathers of the Church, notably Saint Athanasius in his fight against Arianism, developed this theology of divine being. If God is "he who is," then Christ, the incarnate Word, fully participates in this divine being. He is not a creature, however elevated, but the "I am" himself made man. This affirmation protects the Christian faith from a relapse into polytheism or into a subtle form of idolatry that would make Christ a simple religious hero. The "I am" of the burning bush guarantees the uniqueness and transcendence of God, while opening up the possibility of a true incarnation.

The presence that accompanies and liberates

If the transcendence of the "I am" liberates from idolatry, its presence liberates from oppression. The immediate context of the revelation of the divine name is the suffering of Israel in Egypt. God declares to have seen the misery of his people, to have heard their cries, to know their suffering. This triple affirmation—seeing, hearing, knowing—expresses an active divine empathy. The "I am" is not an abstract philosophical principle indifferent to the fate of humankind, but a God who personally engages in history to liberate the oppressed.

This liberating dimension of the divine name runs throughout Scripture. After the revelation of the burning bush, Moses returns to Egypt and, in the name of the "I am," confronts the pharaoh. The ten plagues that fall upon Egypt demonstrate the superiority of the God of Israel over all the Egyptian deities. The tenth plague, the death of the firstborn, culminates in the institution of Passover, a perpetual memorial of liberation. The crossing of the Red Sea completes the deliverance: the waters that engulf the Egyptian army part to let the people of God pass through. In all these events, the presence of the "I am" is manifested as the power of life against the forces of death and slavery.

This liberating presence does not stop with the historical Exodus. It continues in the cloud and the pillar of fire that guide Israel in the desert, in the manna that nourishes each day, in the water gushing from the rock. The "I am" concretely accompanies his people in all the trials of the journey. When later the people settle in the promised land, the temple of Jerusalem will become the symbolic place of this presence, but the prophets will never cease to remind us that God cannot be contained in a stone building: his presence overflows all places, his being fills heaven and earth.

This theology of liberating presence finds its fulfillment in Christ. The name "Emmanuel," given to Jesus in the Gospel of Matthew, means "God with us." The eternal "I am" becomes an incarnate presence, sharing our condition, taking on our suffering, dying our death to free us from it. The resurrection of Christ manifests the definitive victory of the "I am" over all the powers of oppression and death. And the promise of the Risen One, "I am with you always, even to the end of the age," extends the presence of the God of the burning bush to us.

In our personal spiritual life, this presence of the "I am" frees us from existential solitude, from the feeling of abandonment, from despair in the face of trials. We are never alone: the one who IS is with us, in us, for us. This certainty does not exempt us from efforts or struggles, but it gives us inexhaustible inner strength. Saint Teresa of Avila expressed this awareness of the divine presence magnificently: "God alone is enough." When we possess the "I am," when we are possessed by it, nothing can truly be lacking or destroy us.

The personal commitment that establishes the alliance

The third axis of understanding "I am that I am" concerns God's personal commitment to a covenant relationship. The name revealed at the burning bush is not neutral information about the divine nature, but the introduction to a relationship. God does not simply say, "This is who I am," but "This is who I am for you, this is who I will be with you." Theologian Bruce Waltke summarizes this dimension well: "I am who I am for you." The divine name expresses a presence oriented toward us, a being-for-the-other that defines God's very love.

This personalization of the divine name manifests itself immediately after revelation. God does not simply say "I am," he adds: "the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, the God of Jacob." He defines himself by his relationships, by the covenants he made with the patriarchs, by the history he shared with them. This relational definition complements the ontological definition. God is the absolute being, but this absolute being chooses to enter into relationships, to bind himself through promises, to engage in a common history with concrete people.

The covenant made at Sinai, a few weeks after the revelation of the burning bush, sealed this mutual commitment. God offered his protection, his presence, his law of life; the people committed themselves to worshipping only him and following his commandments. This covenant was not a commercial contract between equal partners, but a pact of fidelity in which God took the initiative and man responded freely. The "I am" became "I am your God," and Israel responded "You are our God." This reciprocity founded the identity of Israel and, more broadly, the identity of every believer.

The personal commitment of the "I am" culminates in the incarnation and the cross. Saint John, in his prologue, affirms that the Word "was with God and the Word was God," taking up the language of absolute being. But this Word "became flesh and dwelt among us." The divine being commits himself to the point of becoming human, to the point of suffering and dying for love. The cross reveals the unfathomable depth of the commitment of the "I am": God is not only with us in good times, he is with us in the abyss of suffering and death. He transforms these realities from within into paths of life and resurrection.

For our life of faith, this relational dimension of the "I am" changes everything. God is not a philosophical principle to be contemplated from afar, but a living person to be loved and spoken to. Prayer becomes a dialogue with the "I am," not an anguished monologue in the face of emptiness. Obedience to the commandments becomes a loving response to the one who first loved us. The sacraments become real encounters with the presence of the "I am" in our flesh and our history. Our entire existence can unfold under the benevolent gaze of the one who calls us by name and says, "I am with you."

Tradition

The Fathers of the Church and the Metaphysics of the Exodus

The patristic tradition has made Exodus 3:14 a pillar of Christian theology. Saint Augustine, in his major works such as "The City of God" and "The Confessions," meditates at length on the "I am that I am." For him, this verse reveals that God is the immutable being par excellence, the one who undergoes no change, no alteration, no corruption. Everything that exists in time is subject to change and therefore partakes of nothingness to the extent that it passes from non-being to being and then returns to non-being. God alone truly IS, in an eternal permanence that transcends time.

This Augustinian meditation establishes an "apophatic theology," that is, a theology that recognizes the inability of human language to fully grasp the divine mystery. Augustine asserts that while we can say what God is not—he is not mortal, not changeable, not composite, not limited—we can never adequately say what he IS. The "I am" always remains beyond our concepts, our images, our formulations. This intellectual humility protects faith from the danger of mental idolatry, which would consist in confusing our ideas about God with God himself.

Saint Thomas Aquinas, in the 13th century, systematized this reflection in his "Summa Theologica." He devoted several questions to the divine name and the being of God. For Thomas, Exodus 3:14 reveals that the essence of God is to exist. In every creature, one can distinguish essence (what it is) from existence (the fact that it is); in God alone, essence and existence coincide perfectly. God does not receive existence from an external source; he IS existence itself, subsisting by itself. From this fundamental intuition, Thomas deduces all the divine attributes: simplicity, perfection, infinity, immutability, eternity, unity.

This "metaphysics of the Exodus," in the words of Étienne Gilson, has profoundly influenced Western theology. It establishes that Christian philosophy is not constructed against biblical revelation but from it. Human reason, enlightened by faith, can meditate on the "I am" and unfold its metaphysical implications without betraying the revealed mystery. This harmony between faith and reason, between revelation and philosophy, characterizes the great Catholic tradition and distinguishes Christianity from a fideism that would scorn intelligence or from a rationalism that would claim to exhaust the mystery.

The Mysticism of the Name in Christian Spirituality

Beyond speculative theology, the "I am" has nourished a rich mystical and spiritual tradition. The Philokalia, a collection of spiritual texts from the Christian East, teaches the "Jesus Prayer" or "prayer of the heart": "Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner." This incessant prayer, repeated in sync with the breath, aims to anchor consciousness in the presence of the "I am" incarnate in Jesus. It gradually transforms the praying person, purifying their heart and uniting them with Christ.

Saint Catherine of Siena, in her mystical writings, constantly speaks of God as "He who is" in contrast to herself who is only "she who is not." This acute awareness of the ontological disproportion between God and the creature does not engender despair but wonder. If God, who IS fully, bends down toward the one who is nothing, it is out of pure gratuitous love. This mystical humility opens one to the experience of divine love in its most radical gratuitousness.

The great Spanish Carmelites of the 16th century, Saint John of the Cross and Saint Teresa of Avila, developed a spirituality of union with God that presupposes the stripping away of all images, all concepts, all sensory consolations. To unite with the "I am," one must agree to pass through the "dark night," that interior purgatory where God seems absent but where in reality he works in the depths of the soul. The ultimate mystical experience, which John of the Cross calls "spiritual marriage," is a participation in the very being of God, a communion so intimate that the soul can say with Saint Paul: "It is no longer I who live, but it is Christ who lives in me." The divine "I am" is communicated to the soul, which becomes, by grace, a participant in the divine nature.

This mystical tradition is not reserved for an elite of contemplatives withdrawn from the world. It calls every baptized person to cultivate a deep interior life, to seek the presence of the "I am" in silence and prayer, and not to be content with a superficial or purely intellectual faith. The sacraments, particularly the Eucharist, are the privileged places where the "I am" gives himself to us under the species of bread and wine. The Mass thus becomes the daily burning bush where Christ, the real presence of the "I am," reveals himself and gives himself as nourishment.

Meditations

How can we make the revelation of Exodus 3:14 not just an object of theological study but a source of spiritual transformation? Here are seven concrete steps to embody the “I am” message in your daily life.

First step Begin each day with a moment of silence where you become aware of the presence of the “I am.” Before you begin your activities, sit quietly, close your eyes, and repeat to yourself, “I am with you.” Let this divine word dwell in your heart. Welcome the presence of God not as an abstract idea but as a living reality that surrounds and penetrates you. Five minutes is enough to anchor your day in this fundamental awareness.

Second step : Identify your personal idols. What in your life takes the place of the "I am"? Money, the way others see us, professional success, health, family? All of these realities are good in themselves, but they become idols when we give them the power to define our identity and worth. Write a list of your potential idols, then ask the "I am" for the grace to put these attachments into perspective and place your ultimate security in it alone.

Third step : Practice lectio divina on Exodus 3:1-15. Read the text of the burning bush slowly, letting it resonate within you. Imagine yourself in Moses' place, hearing God call you by name. What is the "I am" saying to you today? What mission is he sending you on? What are your fears and objections, like Moses? Dialogue with God in prayer, with complete frankness and simplicity. Note the insights that emerge from this meditation.

Fourth step : In times of trial or anxiety, anchor yourself in the “I am.” When you feel overwhelmed by circumstances, when you worry about the future, when you doubt yourself, repeat to yourself or quietly: “I am that I am.” This affirmation is not a magic mantra, but an act of faith: you recognize that God IS, that he remains stable when all else wavers, that he is your rock and your fortress. This simple but powerful practice can transform your relationship with anxiety.

Fifth step : Commit yourself concretely to a work of liberation. The “I am” revealed itself to Moses to free an oppressed people. It continues today to work for liberation from all forms of slavery. Choose a cause where injustice cries out to heaven: the homeless, migrants, victims of violence, the poor, the isolated sick. Give of your time, your skills, your resources. By becoming an instrument of liberation for others, you participate in the very mission of the “I am.”

Sixth step : Cultivate a deep Eucharistic practice. If you are Catholic, approach the Eucharist with a renewed awareness that Christ, the incarnate “I am,” truly gives himself to you. Before Communion, open your heart to welcome the one who IS. After Communion, remain in silence of thanksgiving, allowing the presence of the “I am” to transform you from within. If you cannot receive sacramental Communion, practice spiritual Communion, asking Christ to come and dwell within you.

Seventh step : End each day with an examination of conscience centered on the presence of the “I am.” Reread your day not primarily from a moral perspective (what have I done well or badly?) but from the perspective of presence: where did I recognize the “I am” today? In which people, in which situations, in which events? Where did I fail to recognize it? Where did I ignore or reject it? Thank God for his faithful presence, ask forgiveness for your blindness, renew your desire to live in communion with him. Then place yourself in his hands for the night.

Conclusion

The revelation of Exodus 3:14—“I am who I am”—is one of the pinnacles of Scripture and theology. It reveals to us a God who infinitely transcends all our categories, who IS in the absolute fullness of being, who escapes all attempts at manipulation or idolatry. At the same time, this infinitely transcendent God reveals himself to be infinitely close, engaged in our history, present in our struggles, faithful to his promises. The “I am” is not a philosophical abstraction but a living person who loves us, calls us, and sends us.

This revelation possesses a revolutionary transformative force. It frees us from existential angst by anchoring us in the very being of God. It frees us from idolatry by detaching us from all false securities and attaching us to the only true source of life. It frees us from loneliness by assuring us of an unconditional and unalterable presence. It commits us to a mission of liberation for all the oppressed, like the God who heard the cry of the slaves in Egypt.

To live from the "I am" is to accept a radical conversion of our view of God, of ourselves, and of the world. It is to renounce the illusion of absolute autonomy and to recognize ourselves as creatures totally dependent on the one who IS. It is to abandon the anxious quest for meaning and security in perishable things and to rest in God alone. It is to become witnesses and instruments of his liberating presence in a world thirsting for the absolute and starving for meaning.

The final call of Exodus 3:14 resonates for each of us today. Like Moses in the desert, we are invited to remove the sandals from our feet because the place where we stand—here and now—can become holy ground through the presence of the “I Am.” We are called not to flee the world but to recognize and serve the living God in it. May we, day by day, learn to live in the wonder-filled awareness that the eternal “I Am” is with us, in us, for us. From this awareness will spring inner peace, brotherly love, and the courage of mission. For he who sends us has said, “I will be with you.”

Practical

- Daily Morning Meditation : Spend five minutes each morning welcoming the presence of “I am” in silence, before any activity or distraction.

- Identification and de-idolization : List your personal idols and ask for the grace to place your ultimate security in God alone, the source of all being.

- Weekly Lectio Divina : Meditate on Exodus 3:1-15 once a week, imagining God calling you personally and revealing His name to you.

- Anchoring in the test : When anxiety or doubt assail you, repeat inwardly “I am that I am” as an act of faith in divine permanence.

- Concrete solidarity commitment : Choose a work of liberation for the oppressed in which you will regularly invest, thus participating in the mission of the liberating “I am”.

- Eucharistic Deepening : Approach the Eucharist with the renewed awareness that Christ, “I am” incarnate, truly gives himself to you under the species of bread.

- Evening attendance exam : Each evening, review your day, identifying where you acknowledged the presence of the “I am” and where you ignored it, concluding with thanksgiving.

References

- Biblical text : Exodus 3:1-15, particularly verse 14 in its various French translations (Jerusalem Bible, TOB, New Segond Bible).

- Patristic : Saint Augustine, From Trinitate And The City of God, for the theology of the immutable and eternal being of God.

- Medieval Theology : Saint Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica I, questions 2-13, on the existence and nature of God from Exodus 3:14.

- Mystical spirituality : Saint Catherine of Siena, The Dialogue, on the contrast between “He who is” and “she who is not”.

- Eastern tradition : Philokalia, a compilation of texts on prayer of the heart and the continual awareness of the divine presence.

- Carmelite mystic : Saint John of the Cross, The Ascent of Carmel And The Dark Night, on the transforming union with the “I am”.

- Contemporary exegesis : Bruce Waltke and other biblical commentators on the relational meaning of the divine name: “I am who I am for you.”

- Christian philosophy : Etienne Gilson, The Spirit of Medieval Philosophy, on the “metaphysics of the Exodus” and the influence of Exodus 3:14 on Western thought.