BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE ON ST. MARK

Who is this St. Mark, to whom tradition has always unanimously attributed the composition of the second canonical Gospel? Most exegetes and critics agree that he is no different from the figure mentioned alternately in several writings of the New Covenant under the names of John, Acts of the Apostles 13, 5, 13; by Jean-Marc, Acts of the Apostles 11, 12, 25; 15, 37, and of Mark, Acts of the Apostles 15, 39; Colossians 4, 10, etc. (See Drach (Commentary on the Epistles of St. Paul, p. 503), etc.) Others, on the contrary, deny this identity. For them, the evangelist St. Mark would be completely unknown; or else, he should be confused with the apostolic missionary whom St. Peter calls "my son Mark" in his First Letter, 5:13. Other authors, going even further, distinguish the evangelist St. Mark, John Mark, and another Mark, a relative of St. Barnabas. Cf. Colossians 10. But these multiplications do not rest on very solid foundations. Although several apostolic writers of the first centuries, in particular Dionysius of Alexandria and Eusebius of Caesarea, seem vaguely to suppose the existence of two distinct Marks, one of whom would have been a companion of St. Peter, the other a collaborator of St. Paul, it cannot be said that tradition ever definitively settled the matter. this point. We will also say, taking Theophylact as a guide: αὐτοῦ δ Πέτρος ὀνομάζει… Ἐϰαλεῖτο δὲ ϰαὶ Ἰωάννης· ἀνεψιὸς δέ Βαρνάϐα. ἀλλὰ ϰαί Παύλου συνέϰδημος· τέως μέντοι Πέτρῳ συνὼν τὰ πλεῖστα, ϰαὶ ἐν Ῥώμη συνῆν. Proc. Comm. in Evang. Marc. Μάρϰος… ἐϰαλεῖτο δὲ ὁ Ἰωάννης, already wrote Victor of Antioch. cf. Cramer, Cat. 1, p. 263; 2, p. 4.

Our Evangelist received the Hebrew name John, יוחבן, at his circumcision., Jochanan; His parents added to it, or he himself later adopted, the Roman surname of Mark, which, initially joined to the name, soon replaced it completely. Thus, St. Peter and St. Paul, in the passages cited, mention only the Roman surname. St. Mark was the ἀνεψιός of St. Barnabas, that is, the son of the sister of this famous apostle; cf. Colossians 4:10. Perhaps he was a Levite like his uncle; cf. Acts of the Apostles 4, 26 (See Bede the Venerable, Prologue. In MarcumHis mother's name was Married and resided in Jerusalem, Acts of the Apostles 12, 12, although the family originated from the island of Cyprus. cf. Acts of the Apostles 4, 36. Converted to ChristianityWhether before or after the death of the Savior, she equaled in zeal for the new religion the Married of the Gospel, for we see the Apostles and the first Christians gathering in his house for the celebration of the holy mysteries, Acts of the Apostles 12, 12 and following. It is there that St. Peter, delivered from his prison Miraculously, he went directly to seek refuge. This circumstance suggests that close ties already existed between the Prince of the Apostles and the family of St. Mark; it also explains the influence exerted by St. Peter on both the life and the Gospel of John Mark (see below, §4, no. 4). As for the name "son" that Cephas gives him in his first Letter, 5:13, it most likely indicates a lineage established through baptism: it is therefore not merely a term of endearment (several Protestant exegetes, including Bengel, Neander, Credner, Stanley, de Wette, and Tholuck, take the word "son" literally and suppose that Peter is speaking of one of his children. But this hypothesis has no basis whatsoever).

St. Epiphanius; Against Heresies, 51, 6, the author of Philosophoumena7:20, and several other ecclesiastical writers of the early centuries make the evangelist St. Mark one of the seventy-two disciples. It has also been said that after attaching himself early to Our Lord Jesus Christ, he was one of those who abandoned him after the famous discourse delivered in the synagogue of Capernaum. John 6, 6 (Orig., de recta in Deum fide; Doroth., in Synopsi Procop. (diac. ap. Bolland. 25 April). But these two conjectures are refuted by the ancient assertion of Papias: οὔτε ᾔϰουσε τοῦ ΰυρίου οὐτε παρηϰολούθησεν αὐτῷ (Ap. Euseb. Hist. Eccl. 3, 39). It is possible, however, as various commentators have thought, that he was the hero of the interesting incident of which he alone preserved the memory in his Gospel, 14, 51-52 (See the explanation of this passage).

The Acts of the Apostles They provide us with more authentic information about his later life. We read there, first, in 12:25, that Saul and Barnabas, after having brought to the poor of Jerusalem the rich alms sent to them by the Church of Antioch (cf. 11:27-30), took John Mark to Syria; from there, he went with them to the island of Cyprus, when Paul undertook his first great missionary journey (45 AD). But when, after several months' stay on the island, they arrived at Perga, in Pamphylia (See Ancessi, Geographical Atlas for the Study of the Old and New Testaments. pl. 19), from where they were to venture into the most inhospitable provinces of Asia Minor, to carry out a difficult and dangerous ministry, he refused to go any further. He therefore abandoned them and returned to Jerusalem cf. Acts of the Apostles 13 (The reason for his departure is not given; but Paul's subsequent conduct, Acts of the Apostles, 15, 37-39, sufficiently proves that John Mark had not acted irreproachably and that he had momentarily displayed either weakness, inconsistency, or frivolity. cf. St. John Chrysostom, ap. Cramer, Caten, in Acts of the Apostles 15, 38.). Nevertheless, at the beginning of St. Paul's second mission, Acts of the Apostles 15, 36, 37, we find it again at Antiochresolved this time to face all difficulties and dangers for the spread of the Gospel (52 AD). His uncle therefore proposed to Paul that he take him back as an assistant. But the Apostle to the Gentiles refused. “Paul argued to him that the one who had left them in Pamphylia and had not gone with them to the work should not be taken back. There was then a disagreement between them.” St. Paul did not believe he could yield to St. Barnabas’s entreaties; but the Apostles reached an amicable agreement. It was agreed that Paul would go and evangelize the Syria and Asia Minor with Silas, while Barnabas, accompanied by Mark, would return to Cyprus. This disagreement caused by John Mark thus served Providence's plans for the more rapid spread of the good news.

From this moment on, we lose sight of the future evangelist: but tradition teaches, as we shall see later, that he became the regular companion of St. Peter; cf. 1 Peter 513. However, he was not forever separated from St. Paul. We like to find him in Rome, around the year 63, near that great apostle who was then a prisoner there for the first time. Colossians 4:10; Philemon 24. We love to hear Paul, during his second imprisonment (cf. 2 Timothy 4:11, around the year 66), earnestly urging Timothy to bring Mark to him, whom he longed to see before he died. Blessed St. Mark, who had the good fortune to enjoy, for a significant part of his life, such close relationships with the two illustrious Apostles Peter and Paul.

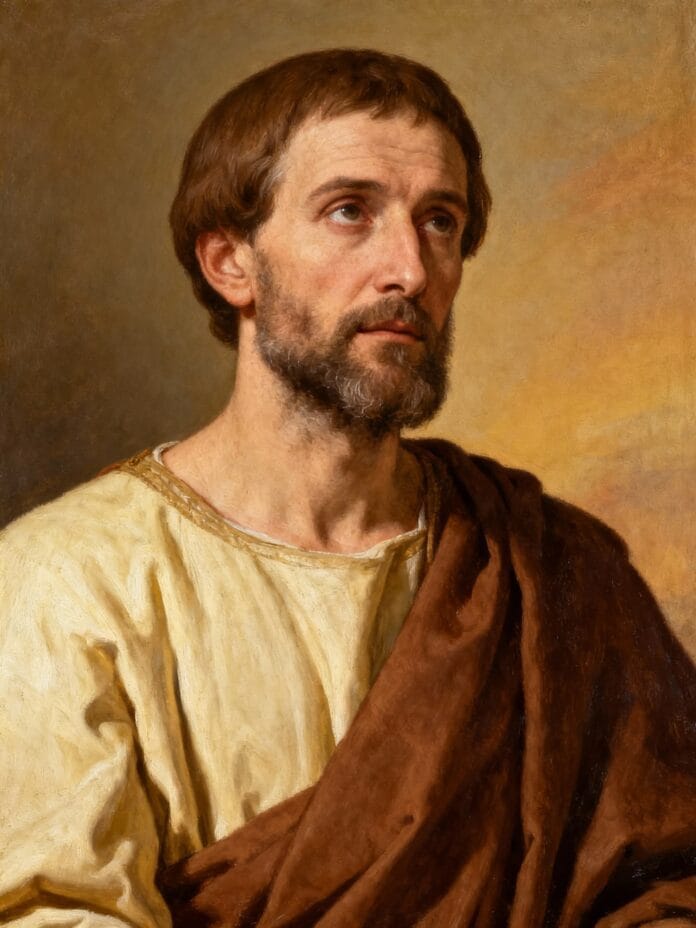

We have very little information about the rest of his apostolic work and about his death. The Fathers, however, state explicitly that he evangelized Lower Egypt and founded the Church of Alexandria, of which he was the first bishop. (A tradition that seems legendary claims he won the favor and admiration of the famous Jew Philo; cf. Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 2, 16; St. Jerome, De Vir. Illustri. c. 8; St. Epiphanius, Haer. 51, 6.) According to a very plausible conjecture by St. Irenaeus, adv. Mark 3, 1, his death would have occurred only after that of St. Peter, therefore after the year 67. Several ancient writers assert that it consisted of a painful but glorious martyrdom inflicted upon him by the people of Alexandria; cf. Nicephorus, Ecclesiastical History 2, 43; Simeon, Metaphor. in Martyr. St. Mark (See D. Calmet, Dictionary of the Bible, under the entry Mark 1). The Church adopted this sentiment, which it recorded in the Breviary and the Martyrology (under April 25). For many centuries, the mantle of St. Mark was kept in Alexandria, with which each new bishop was solemnly invested on the day of his enthronement (the Jesuit Religious Studies, 15th year, 4th series, vol. 5, p. 672 ff., contain an article by M. Le Hir on the Chair of St. Mark, transported from Alexandria to Venice, that is as interesting as it is scholarly). But, while the Evangelist's renown faded in Egypt, Venice revived it in the West: this city has long since chosen St. Mark as its special protector and has built in his honor one of the most beautiful and richest basilicas in the whole world (On Among other treasures, one can see the magnificent painting by Fra Bartholomeo, which depicts our Evangelist. The lion, emblem of St. Mark, is still engraved on the arms of the famous republic. — On the life of St. Mark, see the Bollandists under April 25.

AUTHENTICITY OF THE SECOND GOSPEL

«"The authenticity of the book cannot be doubted," Dr. Fritszche rightly said (Evangelium Marci, Lips. 1830, Proleg. §5). It is just as certain as that of the Gospel according to St. Matthew; the Fathers of the first centuries affirm, in fact, in common agreement that St. Mark is truly the author of a Gospel, and there is not the slightest reason to doubt that this Gospel is the one that has come down to us.

1. Direct Testimonies. — Here again, Papias leads the way. «The priest John,» he says (Ap. Euseb. Hist. eccl. 3, 39), “reports that Mark, having become Peter’s interpreter, accurately recorded in writing everything he remembered; but he did not observe the order of things that Christ had said or done, because he had not heard the Lord, nor had he personally followed him.” In these lines, we thus have two authorities combined, that of the priest John and that of Papias.

St. Irenaeus: "Matthew composed his Gospel while Peter and Paul preached the good news in Rome and founded the Church there. After their departure, Mark, the disciple and interpreter of Peter, also delivered to us in writing the things that had been preached by Peter (Against Heresies, 3, 1, 1; ap. Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 5, 8; cf. 3, 10, 6, where the holy Doctor quotes the first and last lines of the Gospel according to St. Mark: «This is why Mark, also the interpreter and disciple of Peter, composed the beginning of the Gospel narrative thus: «The beginning of the gospel of Jesus Christ, the Son of God, as it is written in the prophets: «Behold, I send my angel before your face, who will prepare your way.»«» At the end of the Gospel, Mark says: »And after the Lord Jesus had spoken to them, he was received into heaven, where he sits at the right hand of God.» (Latin: Quapropter et Marcus, interpres et sectator Petri, initium evangelicæ) conscriptionis fecit sic: Initium Evangelii Jesu Christi Fili Dei, quemadmodum scriptum est in Prophetis: Ecce ego mitto angelum meum ante faciem tuam qui præparabit viam tuam… In fine autem Evangelii ai Marcus:Et quidem Dominus Jesus, postquam locutus est eis, receptus est in coelos, et sedet ad dexteram Dei)”. cf. Mark. 1, et seq. ; 16, 19.)”.

Clement of Alexandria: «This is the occasion for the composition of the Gospel according to St. Mark. Peter having publicly taught the word (τὸν λόγον) in Rome, and having expressed the good news in the Holy Spirit, a great number of his listeners asked Mark to commit to writing the things he had said, for he had accompanied him from afar and remembered his preaching. Having therefore composed the Gospel, he delivered it to those who had asked him for it. When St. Peter learned of it, he neither hindered nor encouraged it (Apud Euseb. Hist. Eccl. 6, 14.).»

Origen (Ibid. 6, 25): «The second Gospel is that of St. Mark, who wrote it under the direction of St. Peter.» Tertullian: «Marcus quod edidit Evangelium Petri affirmatur, cujus interpres Marcus (Contr. Marcion 4, 5).» Translation: «The Gospel that Mark published is in accordance with that of Peter.»

Eusebius of Caesarea does not merely point out the assertions of his predecessors; on several occasions he speaks in his own name, and entirely in the same vein. In his Evangelical demonstration, 3, 3, 38 et seq., he says that without doubt the Prince of the Apostles did not compose a Gospel, but that on the other hand S. Mark wrote τὰς τοῦ Πέτρου περὶ τῶν πράξεων τοῦ Ἰησοῦ διαλέξεις. Then he adds: πὰντα τὰ παρὰ Μαρϰὸν τοῦ Πέτρου διαλεξέων εἶναι λέγεται ἀπομνη μονεύματα. «They made all kinds of entreaties to Mark, the author of the Gospel which has come down to us and the companion of Peter, so that he would leave them a book which would be a memorial of the teaching given orally by the apostle, and they did not cease their requests until after having been granted. They were thus the cause of the writing of the Gospel according to Mark. » (cf. Ecclesiastical History book 2, ch. 15).

S. Jerome: «at the request of the brothers of Rome, Mark, disciple and interpreter of Peter, briefly wrote a gospel, according to what he had heard of Peter's preaching» [«Marcus discipulus et interpres Petri, juxta quod Petrum referentem audierat, rogatus Romæ a fratribus, breve scripsit Evangelium». De viris illustr. c. 8.] «Mark, whose gospel had been composed by writing from the stories of Peter» [«Marcus,.. cujus Evangelium, Petro narrante et illo scribente, compositum est»] letter 120, 10, ad Hedib.

We could cite further identical statements from St. Epiphanius, St. John Chrysostom, and St. Augustine; but the preceding testimonies sufficiently show that there was only one voice in the early Church to attribute to St. Mark the composition of the second of our Gospels.

2. Indirect testimonies are less numerous than for the other three biographies of Jesus, and this is not surprising. The work of St. Mark is indeed the shortest of all. Moreover, it deals almost exclusively with history and facts: it has almost nothing didactic about it. Finally, most of the details it contains are found in the Gospel according to St. Matthew. For all these reasons, ancient writers cited it less frequently than the others. Nevertheless, it has not been forgotten. St. Justin (Dialogue with Tryphon (c. 56) reports that the Savior gave two of his Apostles the name "Sons of Thunder" (Βοανεργές, ὅ ἔστιν υἱοὶ βροντῆς). Now, only St. Mark recounts this event, 3:17. The same author (ibid., c. 103) also says that the Gospels were composed by Apostles or by disciples of the Apostles: this latter characteristic necessarily applies to St. Mark and St. Luke. Compare also Apolog. 1, c. 52, and Mark. 9:44, 46, 48; Apolog. 1, c. 16, and Mark. 12, 30. The Valentinians also prove, through indirect quotations, that there existed in their time a Gospel quite similar to the one we now possess under the name of St. Mark. Cf. Irenaeus, Against Heresies, 1, 3; Epiphanius, Apostles 33; Theodoti, Eclogue, c. 9. Similar allusions are found in the writings of Porphyry. Finally, we know that the Docetists preferred this Gospel to the other three (“They were the ones who separated Jesus from Christ, who said that Christ remained the one who cannot be born, and that it is Jesus who was truly born. They prefer theGospel according to Saint MarkBut, if they read it with love of the truth, they can be corrected.” “Qui Jesum separant a Christo et impassibilem perseverasse Christum, passum vero Jesum dicunt, id quod secundum Marcum est præferentes Evangelium, cum amore veritatis legentes illud, corrigi possunt. » S. Irenaeus, Against Heresies, 3, 11, 17; cf. Philosophum 8, 8. On the contrary, the Ebionites gave their preferences to the first Gospel and the disciples of Marcion to the third).

Moreover, in the absence of all these direct and indirect testimonies, its mere presence in the Syriac and Italic versions, composed in the second century, would be sufficient guarantee of its authenticity. Thus, to deny that it was the work of St. Mark, one needed the audacity of rationalism (M. Renan, in his work the Gospels and the second generation of Christians, admits the authenticity of our Gospel (cf. p. 114). A remark by Papias had led our modern hypercritics to maintain that the first Gospel was much later than the apostolic era (cf. our Commentary on the Gospel according to St. Matthew, Preface, § 2); a remark by the same Father also led them to say that the second Gospel, in its present form, could not have been written by St. Mark. In the text we quoted above, Papias, describing the composition of St. Mark, pointed out this particular feature: ἔγραψεν οὐ μέντοι τάξει. Now, object Schleiermacher, Credner, and the followers of the Tübingen school, there is a remarkable order in the second Gospel as we read it today; everything is generally well arranged. Consequently, the book originally written by St. Mark has been lost, and the biography of Jesus that has been transmitted to us under his name has been falsely attributed to him, for it is of a much more recent date. — If one reads Papias's text carefully, one sees that he does not attribute an absolute lack of order to St. Mark's writing. Here is the true thought of the holy bishop: Mark wrote with great accuracy what Jesus Christ did and taught; but it was not possible for him to impose a rigorous historical order on his account since he had not been an eyewitness. He confined himself to recounting from memory what he had learned from St. Peter. But when the Prince of the Apostles had to speak of the actions or teachings of Jesus, he did not adhere to a fixed order; he adapted each time to the needs of his listeners. Understood in this way, and this is their true meaning, Papias's words prove absolutely nothing against the authenticity of the second Gospel. It is quite certain, in fact, that St. Mark's narrative does not always adhere to chronological order. St. Jerome already affirmed this, "juxta fidem magis gestorum narravit quam ordinem" "Rather according to the historical truth of the events than according to their chronological order."Comm. in Matth. Proœm.), and negative criticism is itself forced to admit that the second Gospel reverses the actual sequence of events more than once. The words οὐ μέντοι τάξει of the priest John and Papias therefore mean "not in the actual order," and they are sufficiently justified even by the present state of the writing of Saint Mark. (Others translate them as "incomplete series," alluding to the gaps found in the second Gospel even more than in the other three; but this interpretation is less natural, although it also resolves the difficulty very well.)

Eichhorn and de Wette raised another objection. After careful calculation, they discovered that the details specific to St. Mark do not exceed twenty-seven verses: the entire rest of the Gospel bearing his name is found almost word for word in the redaction of St. Matthew or St. Luke. Clearly, they concluded, it is not an original work, but a later fusion of the other two synoptic Gospels. For a response, we refer these two critics to the numerous and clear assertions of tradition, which attribute to St. Mark, disciple and companion of St. Peter, the composition of a Gospel distinct from those of St. Matthew and St. Luke (see also what will be said below, §7, concerning the character of the second Gospel).

INTEGRITY

While some doubts have sometimes been raised regarding the authenticity of the first two chapters of St. Matthew (See our Commentary on the First Gospel, (Preface, p. 9), a veritable storm of protests has been stirred up concerning the last twelve verses of St. Mark, 16, 9-20.

These are the reasons we relied on to reject them as an interpolation.

First, there is extrinsic evidence, which can be reduced to two main sources, one from manuscripts, the other from ancient ecclesiastical writers. — 1° Several Greek manuscripts, among which the Codex Vaticanus and the Codex Sinaiticus, That is to say, the two oldest and two most important ones, completely omit this passage. Similarly, the Codex Veronensis Latin. Among those which contain it, there are some which surround it with asterisks, as doubtful (For example, Codd. 137 and 138.); others are careful to note that it is not found everywhere (see Codd. 6 and 10, where we read the following remark: until the end of verse 8) πληροῦται ὁ εὐαγγελιστής). Furthermore, the text is in rather poor condition in this passage: variants abound, which, we are told, is far from favorable to its authenticity. — 2° St. Gregory of Nyssa (Oration on Resurrection), Eusebius (Ad Marin, Quaest. 1), St. Jerome (Ad Hedibus 4, 172), and a considerable number of other ancient writers, assert that, even in their time, the passage in question was missing from most manuscripts, so that it was regarded by many as a relatively recent addition. The first Chains Greeks do not comment beyond verse 8, and it is also at this verse that the famous canons of Eusebius stop.

To the extrinsic evidence, we add an intrinsic argument, supported by the extraordinary change of style that is noticeable from verse 9 onwards. 1° In these few lines that conclude the second Gospel, we encounter no fewer than twenty-one expressions that St. Mark had never used before (For example, verse 10, πορευθεῖσα, τοῖς μετʹ αὐτοῦ γενομένοις; verse 11, ἐθεάθη, ἠπίστησαν; verse 12, μετὰ ταῦτα; verse 17, παραϰολουθήσει; verse 20, ἐπαϰολουθούντων, etc.). 2. The picturesque details, the formulas of rapid transition which characterize, as we will say later, the narration of our evangelist, disappear abruptly after verse 8. This new style would therefore presuppose, even require, an author distinct from the first.

This is the conclusion that most Protestant exegetes draw from this twofold argument: according to them, the original work of St. Mark ends at verse 8 (others are an exception and declare themselves in favor of the authenticity of verses 9-10). They generally admit, however, that the last verses date back to the end of the first century. We, on the contrary, maintain, along with all Catholic commentators, that the passage in question is from St. Mark as well as the rest of the Gospel, and it seems to us quite easy to demonstrate this. 1. While two or three manuscripts omit it (it should be noted that Codex B leaves a sufficient gap between verse 8 and the beginning of the Gospel according to St. Luke to accommodate the omitted verses if necessary. This proves that the scribe had doubts about the legitimacy of his omission.), all the others contain it, in particular the famous Codex. ACD, to whose testimony critics attach so much importance (See the nomenclature of the principal manuscripts of the Bible in M. Drach, Epistles of St. Paul, p. 87 ff.). 2° It is found in most of the ancient versions, especially in the Itala, the Vulgate, the Peschito, the Memphis, Theban, Ulphilas, etc. translations. The Syriac version, of which Dr. Cureton discovered important fragments, contains the last four verses (cf. Cureton, Remains of a very ancient recension of the four gospels in Syriac, hitherto unknown in Europe, London, 1858; Le Hir, A study of an ancient Syriac version of the Gospels, Paris 1859.) 3. Several writers of the apostolic age make clear allusions to it (for example, the letter of St. Barnabas, § 45; the Shepherd of Hermas, 9, 25). St. Irenaeus quotes it (see § 2, p. 4, note 5. Compare St. Justin Martyr, Apol. 1, 45); St. Hippolytus, Tertullian, St. John Chrysostom, St. Augustine, St. Ambrose, St. Athanasius, and other Fathers know it and also mention it. Theophylact made it the subject of a special commentary. How is it possible, we might ask those who oppose its authenticity, that an apocryphal passage should have been accepted so widely? 4. Would one understand, we might ask again, that St. Mark ended his Gospel with the words ἐφοϐοῦντο γάρ (16:8), in the most abrupt manner? «Without these verses» (verses 9–20), as Bengel (Gnomon, hoc loco) aptly puts it. «One can hardly admit that the original text ends in such an abrupt way.» Renan, the Gospels, 1878, p. 121), “The story of Christ, especially of the resurrection, ends abruptly, without having had a conclusion.” 5° The substance of this passage, whatever one may say, “has nothing that is not in the rapid and brief style of the evangelist (St. Mark); it also summarizes St. Matthew, and adds to it some details, 16:13, which St. Luke will take up again to expand upon” (Wallon, From the belief due to the Gospel, p. 223). 6° As for the «extraordinary» expressions used here by the narrator, most of them are very common, or else they stem from the particular nature of the subject. Their significance has therefore been singularly exaggerated (cf. Langon, General description of the instructions in the NT. 1868, p. 40. Let us add that verses 9-20 of chapter 16 contain several phrases considered characteristic of St. Mark's style (e.g., verse 12, ἐφανερώθη; verse 15, ϰτίσει; etc. See the commentary). Several authors have conjectured that the death of St. Peter or the persecution of Nero may well have suddenly interrupted St. Mark before he had put the finishing touches on his Gospel, so that the ending would have been written a little later, which would explain the change in style; but this hypothesis seems rather strange (We will say the same of that of Mr. Schegg, Gospel according to Markus, (vol. 2, p. 230, according to which verses 9-20 are a fragment of ancient catechesis inserted by St. Mark himself at the end of his narrative). In any case, it is devoid of any external basis. 7. Finally, two main reasons can account for the disappearance of our twelve verses in a number of manuscripts. 1. Some copyist may have inadvertently omitted them from an earlier manuscript, which led to their subsequent omission in the copies for which this manuscript later served as a model: when they had thus disappeared from a number of codices, it is understandable that a period of hesitation arose regarding them; 2. the difficulty of reconciling verse 9 with the parallel lines of St. Matthew 28:1 must have contributed to casting doubt on the authenticity of the entire passage it begins. These proofs seem to us to be more than sufficient for us to be justified in admitting the perfect integrity of the Gospel according to St. Mark.

ORIGIN AND COMPOSITION OF THE SECOND GOSPEL

Under this heading, we will briefly discuss the following four points: the occasion, the purpose, the recipients, and the sources of the Gospel according to St. Mark.

1. In texts cited above (§ 2, pp. 4 and 5), Clement of Alexandria and St. Jerome clearly indicated, according to tradition, the occasion which inspired the second evangelist to think of writing in turn the biography of Jesus. Christians Having been urged by Rome to compose for them an abridgment of the preaching of the Prince of the Apostles, he yielded to their desire and published his Gospel.

2. His aim as a writer was therefore both catechetical and historical. He wished to help preserve the memory of these pious petitioners and thus continue Christian teaching among them, and it was through a brief summary of the events that make up the Savior's story that he undertook to render them this twofold service. In reality, "the character of the second Gospel is perfectly consistent with this fact, for one perceives no other intention than that of the narrative itself; it presents no didactic section of disproportionate length compared to the rest of the narrative" (Wetzer and Welte, Encyclopedic Dictionary of Catholic Theology, s.v. Gospels). To this catechetical and, above all, historical aim, did St. Mark not add a slight dogmatic tendency? Several authors have thought so, and there is nothing to prevent us from seeing with them the first words of the second Gospel, "The beginning of the gospel of Jesus Christ, the Son of God." », an indication of this tendency. According to this, St. Mark would have intended to demonstrate to his readers the divine sonship of Our Lord Jesus Christ. But this intention is nowhere emphasized: the Evangelist lets the facts speak for themselves; he does not support a direct thesis in the manner of St. Matthew or St. John (See our Commentary on the Gospels of St. Matthew and St. John, Preface). There is a long way from such a simple tendency to the strange aim that several rationalists have attributed to St. Mark. According to them, while the Gospels according to St. Matthew and St. Luke are partisan writings, intended, in the minds of their authors, to support, the former the Judaizing faction (Petrinism), the latter the liberal faction (Paulinism), between which, we are assured, the members of the Christianity In his early work, St. Mark supposedly adopted an intermediate position in his narrative, deliberately placing himself on neutral ground in order to effect a successful reconciliation. On the other hand, Hilgenfeld classifies St. Mark among the Pauline theologians. As we can see, we need not refute these fanciful hypotheses, since they contradict each other.

3. St. Matthew wrote for Christians who had come from the ranks of Judaism, while St. Mark addresses converts from paganism. Apart from the testimonies of tradition (see above, no. 1), according to which the first recipients of the second Gospel were the faithful of Rome, who had largely belonged to paganism (see Drach, Epistles of St. Paul, p. 375), a simple examination of St. Mark's account would allow us to conclude this with a very high degree of probability. 1. The evangelist takes care to translate the Hebrew or Aramaic words inserted in his narrative, for example Boanerges, 3, 17, Talitha cumi, 5, 41; Qorban, 7, 11; Bartimaeus, 10, 46; Abba, 14, 36; Eloï, Eloï, lamma sabachtani, 15, 34: he was therefore not addressing Jews. 2° He gives explanations on several Jewish customs, or on other points that people outside Judaism could hardly know. Thus, he tells us that "Jews do not eat unless they have frequently washed their hands," 7, 3, cf. 4; that "the Passover lamb was sacrificed on the first day of unleavened bread," 14, 12; that "Paraskev" was "the day before the Sabbath," 15, 42; that the Mount of Olives is located ϰατέναντι τοῦ ἱεροῦ, 13, 3, etc. 3° He does not even mention the name of Jewish Law; Nowhere does he, like St. Matthew, make arguments based on texts from the Old Testament. Only twice, in 1, 2, 3 and 15, 26 (assuming this second passage is authentic; see the commentary), does he quote the writings of the Old Covenant in his own name. These are again significant features regarding the purpose of the second Gospel. 4. The style of St. Mark has a great deal of affinity with Latin. «It would seem,» says Mr. Schegg (Evangel. Nach Markus, p. 12), that it was a Roman mouth who taught Greek to our evangelist.» Greekized Latin words frequently recur under his pen, vg σπεϰουλάτωρ, 6, 27; ξέστης (sextarius), 7, 4, 8; πραιτώριον, 15, 16; φραγελλόω (flagello), 15, 15; ϰῆνσος, 12, l4; λεγεών, 5, 9.15; κεντύριων, 15, 39, 44, 45; κοδράντης (quadrans), 12, 42; etc. (Other New Testament writers sometimes use some of these expressions; but they do not use them consistently, like St. Mark.) After mentioning a Greek coin, λεπτὰ δύο, he adds that it was equivalent to the Roman «quadrans»; 12, 42. Further on, 15, 21, he mentions a circumstance of little importance in itself « Simon of Cyrene, the father of Alexander and Rufus» but this is immediately explained if we remember that Rufus lived in Rome. cf. Romans 1626. Do not these last details prove that St. Mark wrote among Romans and for Romans?

4. In our General Introduction to the Holy Gospels, we studied the delicate question of the common source from which the first three evangelists drew in turn: it can therefore only be a source specific to St. Mark. Now, we have heard the Fathers affirm unanimously (See the texts cited in favor of the authenticity of the second Gospel, § 2) that the catechesis of the Prince of the Apostles served as the basis for St. Mark in the composition of his narrative. «Omit nothing of what he had heard, admit nothing that he had not learned from the mouth of Peter»: thus expressed Papias (Loc. Cit.: ἑνὸς γὰρ ἐπὸιήσατο πρόνοιαν, τοῦ μηδὲν ὦν ἤϰουσε παράλιπεῖν, ἢ ψεὐσασθαί τι ἐν αὐτοῖς). Hence the title of ἑρμηνευτὴς Πέτρου, «interpres Petri», which our evangelist has carried since the time of the priest John: hence the name «Memoirs of Peter» applied by S. Justin to his composition (Dialog. c. 106: ἑνὸς γὰρ ἐπὸιἡσατο πρόνοιαν, τοῦ μηδὲν ὦν ἤϰουσε παράλιπεῖν, ἤφεὐσασθαί τι ἐν αὐτοῖς). Not, certainly, that these expressions should be understood too literally, and that St. Mark should be made into a mere "Amanuensis" to whom St. Peter dictated the second Gospel, just as Jeremiah had once dictated his Prophecies to Baruch (According to Reithmayr, the word "interpreter" would mean that St. Mark translated St. Peter's Greek instructions into Latin. According to others, it is the text Aramaic of St. Peter, which Mark would have translated into Greek. (Explanations that are certainly very improbable.) The influence of St. Peter, in all likelihood, was not direct, but only indirect, and it did not prevent the disciple from remaining a very independent historian. It was considerable, however, since it has been so frequently noted by ancient writers. Moreover, it has left numerous and distinct traces in the writing of St. Mark. Yes, the second Gospel is clearly marked with the image of the Chief of the Apostles: all commentators repeat this ad nauseam (See on this point some astute observations in M. Bougaud, THE Christianity and the present times, (vol. 2, pp. 69 ff., 2nd ed.). Since Mark was not an eyewitness to the events he recounts, who could have given his Gospel this freshness of narrative, this meticulousness of detail, which we will soon have to mention? He had not contemplated the work of Jesus with his own eyes, but he had seen it, so to speak, through the eyes of St. Peter ("It is said that everything one reads in Mark is a commentary on the accounts and preachings of Peter." Eusebius). Dem. Evang. l. 3, c. 5. «St. Mark,” said Mr. Renan, Life of Jesus, 1863, p. 39, is full of meticulous observations undoubtedly from an eyewitness. There is nothing to prevent this eyewitness, who evidently had followed Jesus, loved him, and observed him very closely, retaining a vivid image of him, from being the apostle Peter himself, as Papias suggests."). Why is the information concerning Simon Peter more abundant in his work than anywhere else? He alone tells us that Peter went in search of Jesus the day after the miraculous healings performed in Capernaum, 1:56; cf. Luke 4:42. He alone recalls that it was Peter who drew the attention of the other Apostles to the rapid withering of the fig tree, 11:21; cf. Matthew 21:17 ff. He alone shows St. Peter questioning Our Lord Jesus Christ on the Mount of Olives concerning the destruction of Jerusalem, 13:3; cf. Matthew 24:1; Luke 21:5. He alone has the good news delivered directly to Peter by the Angel. the resurrection of Jesus, 16:7; cf. Matthew 28:7. Finally, he describes with particular precision the threefold denial of St. Peter; cf. Especially 14:68, 72. Did he not derive these various traits from Simon Peter himself? It is true, on the other hand, that several important or honorable details of St. Peter's Gospel life are completely passed over in silence in the second Gospel, for example, his walking on water, Matthew 14:28-34; cf. Mark 6:50-51; his prominent role in the miracle of the didrachm, Matthew 17:24-27; cf. Mark 9:33; his designation as the unshakeable rock upon which the Church would be built, Matthew 16:17-19; Mark. 8, 29, 30; the special prayer that Jesus Christ offered for him so that his faith might never fail; Luke 22:31-32 (Compare also Mark 7:17 and Matthew 15:45; Mark 14:13 and Luke 22:8). But do not these remarkable omissions prove once again, as Eusebius of Caesarea already conjectured (Dem. Evang. 3, 3, 89) and St. John Chrysostom (Hom. in Matth.), the participation of St. Peter in the composition of the second Gospel, this great Apostle having wished out of modesty that events which were so precious to his person should be left in oblivion? We readily admit this, following the majority of exegetes (We do not believe that one can draw a peremptory proof from certain coincidences of thoughts and expressions which exist between the Letters of St. Peter and various passages of the second Gospel (V. g. 2 Peter 2, 1, cf. Mark 13, 22; 2 Peter 3, 17, cf. Mark 13, 23; 1 Peter 1, 25, cf. Mark 13, 21; 1 Peter 2, 9, cf. Mark 13, 20; 1 Peter 2, 17, cf. Mark 12, 17; 1 Peter 2, 25, cf. Mark 6, 34; 2 Peter 3, 41, cf. Mark 13, 19; etc.): these coincidences are in fact not characteristic.).

What then should we think of St. Augustine's opinion, quite isolated in antiquity but often accepted since, that the Gospel according to St. Mark is merely an abridgment modeled on that of St. Matthew? «Marcus Matthæum subsecutus tanquam pedissequus et breviator ejus» «Mark followed Matthew step by step, and is the one who abridgmented him (De consens. Evang. l. 1, c. 2)?» It is correct if it simply affirms that there is a great resemblance, either in content or in form, between the first two Gospel narratives; it is false, on the contrary, if it claims that St. Mark merely published a reduction of his predecessor's work. The facts he reports are indeed the same for the most part (However, significant omissions should be noted, particularly Matthew 3:7-40; 8:5-13, etc.; 10:15-42; 11; 12:38-45; 14:34-36; 17:24-27; 18:10-35; 20:1-16; 21:14-16, 28-32; 22:1-14; 23; 27:3-40, 62-67; 28:11-15, 16-20; etc., etc. A person who had simply abridged the text would not have behaved in this way), but he He almost always presents them in a very new way, which proves his complete freedom as a writer. (If, with Mr. Reuss, we divide the material contained in the first three Gospels into 100 sections or paragraphs, we find only 63 of these sections in St. Mark, while St. Matthew has 73, and St. Luke 82. 49 sections are common to the three Evangelists, 9 to St. Matthew and St. Mark, 3 to St. Mark and St. Luke; St. Mark has only two that are entirely unique to him. But how many features are found only in his narrative! Cf. 2:25; 3:20-21; 4:26-29; 5:4-5 ff.; 8:22-26; 9:49; 11:11-14; 14:51-52) ; 16, 9-11, and a hundred other passages which we will point out in the commentary). Moreover, this sentiment is now almost abandoned.

THE PRIMITIVE LANGUAGE OF THE SECOND GOSPEL

Since St. Mark composed his Gospel for Romans, it seemed natural to several critics that he originally wrote it in Latin. This was particularly the opinion of the learned Baronius (Annals, ad ann. 45, § 39 ff. See Tillemont's refutation, Mémoires pour servir à l'Hist. eccl., St. Mark, note 4). The Syriac Peshitta and the superscriptions of several Greek manuscripts undoubtedly affirm that the second Gospel ἐγράφη ῥωμαΐστι; but these anonymous assertions lose all authority in the face of the explicit testimonies of St. Jerome and St. Augustine. "I am speaking of the New Testament," says the first of the two Fathers. (preface to the 4th Gospel at Damasus) which is Greek, without a doubt, with the exception of Matthew who, first in Judea, edited the Gospel of Christ in Hebrew letters.« St. Augustine is no less clear: »Of the four (Evangelists) only Matthew wrote in Hebrew, the others in Greek.«By Consensus. Evangel. l. l, c. 4.)

Why would St. Mark, addressing Romans, not have written in Greek? Was it not in this language that the historian Josephus composed his works, precisely to be understood by the Romans? Did not St. Paul (See Drach, Epistles of St. Paul, p. 7.) and St. Ignatius also write their letters to the Church of Rome in Greek? «For a considerable part of the first centuries,» says Mr. Milman (Latin Christianity, 1, p. 34.), “the Church of Rome and almost all the Churches of the West were, in a sense, Hellenic religious colonies.” Their language was Greek, their writers were Greek, their sacred books were Greek, and many traditions, like many remains, prove that their ritual and liturgy were Greek… All the Christian writings known to us that went to Rome or the West are Greek, or were originally so: the Letters of St. Clement, the Shepherd of Hermas, the Clementine homilies, and the works of St. Justin Martyr, up to Gaius, up to Hippolytus, author of the refutation of all heresies.” Nothing, therefore, prevented St. Mark from writing in Greek, even though he intended his narrative for Latins (See Richard Simon, Histoire critiq. du Nouv. Test. ch. 11; cf. Juven. Sat. 6, 2.).

Wahl's hypothesis, according to which the second Gospel was composed in the Coptic language, hardly deserves a mention (cf. Magazin für alte, besond. oriental. und bibl. Literatur, 1790, 3, 2, p. 8. Wahl cites as a reason the founding of several Egyptian Christian communities by St. Mark.)

TIME AND PLACE OF THE COMPOSITION OF THE SECOND GOSPEL

1° Tradition does not provide us with certain data regarding the time when St. Mark wrote his Gospel; its information is even contradictory. Thus, according to Clement of Alexandria (Hypotyp. 6, ap. Euseb. Hist. Eccl. 6, 44), the second Gospel was published during the lifetime of St. Peter; Whereas, according to St. Irenaeus (Against Heresies, 3, 1: μετὰ τούτῶν (scil. Πέτρου ϰαὶ Παύλου) ἔξοδον. See the full quotation in § 2. The word ἔξοδον can reasonably only refer to the death of the two apostles. «After their departure from this world,» Ruffin had already stated. All other interpretations are arbitrary; it would have appeared only after the death of the Prince of the Apostles, therefore after the year 67. Scholars are divided between these two opinions. Messrs. Reithmayr and Gilly adopt the first, and place the composition of our Gospel between the years 42–49 (Some manuscripts, Theophylact and Euthymius place St. Mark's writing ten or twelve years after the Ascension. Messrs. Langen, J.-P. Lange, and most other exegetes side with St. Irenaeus, which does indeed seem more probable. Other authors attempt to reconcile the patristic testimonies by admitting a double publication of St. Mark's work: the first in Rome before the death of St. Peter, the second in Egypt after his martyrdom. "St. Mark," says Richard Simon (Histoire critiq. du Nouv. Test. t. 1, p. 107), "gave the faithful of Rome a Gospel in his capacity as interpreter of St. Peter, who preached the religion of Jesus Christ in that great city; and he also gave it afterward to the first Christians of Egypt, in his capacity as apostle or bishop." But this is merely a subterfuge without solid foundation. Whatever the case may be So, it is clear from chapters 13, 14 and following that the Gospel according to St. Mark must have appeared before the destruction of Jerusalem, since this event is prophesied there by Our Lord, without anything indicating that it had been fulfilled since.

2. No doubt can remain concerning the place of composition. It was Rome, as all the Fathers who have dealt with this question affirm, with one exception. Clement of Alexandria (Ap. Euseb. Hist. Eccl. 6, 14.) links this belief to an ancient tradition, παράδοσιν τῶν ἀνέϰαθεν πρεσϐυτέρων. St. Irenaeus, St. Jerome, and Eusebius of Caesarea report it as an indubitable fact (See the texts cited above, § 2, 1°.). S. Epiphanius speaks in the same sense: Εὐθὺς δὲ μετὰ τὸν Ματθαῖον ἀϰόλουθος γενόμενος δ Μάρϰος (Hær. 51, 6). S. John Chrysostom, on the contrary, assures that the second Gospel was composed in Egypt. Λέγεται, he says in his Homilies on St. Matthew, ϰαὶ Μαρϰος δὲ ἐν Αἰγύπτῳ τῶν μαθητῶν παραϰαλεσάντων αὐτὸν, αὐτὸ τοῦτο ποιῆσαι. But this isolated sentiment cannot counterbalance the very formal testimonies of all the other ancient writers (Hom. 1, 3). Moreover, the Latinate style and Roman expressions we noted above (see § 4, no. 3, 4°) clearly show that St. Mark must have been writing in Roman territory. From a comparison established between St. Mark 15, 21, and Acts of the Apostles 11, 20, Storr concluded that the city of Antioch had been the homeland of our Gospel; but we confess to not understanding this conclusion, which is moreover universally rejected.

CHARACTER OF THE SECOND GOSPEL

It has often been suggested, and quite rightly so, that the following words of St. Peter be placed at the beginning of the Gospel according to St. Mark, which admirably summarize its general character (See M. Bougaud, lcp 76 et seq.): “You know what has happened throughout Judea, beginning in Galilee, after the baptism that John preached; you know how God anointed Jesus of Nazareth with the Holy Spirit and with power, and how he went around doing good and healing all who were oppressed by the devil, because God was with him.” Acts of the Apostles 10, 37, 38. We find there indeed a striking portrait of Jesus of Nazareth. However, this portrait is not, as in the first Gospel, 1, 1, that of "the Son of David and Abraham", that is to say of the Messiah; nor, as in the third Gospel, that of "the Son of Adam who was Son of God", Luke, 3, 38: it is the portrait of the Redeemer God, incarnate for our salvation, doing good, performing many miracles among men, developing his mission much more by works than by words.

This portrait seems at first glance remarkably concise. The Second Gospel is indeed the shortest of all: a “summarized gospel,” as St. Jerome already called it (De viris illustr. c. 8). It has only sixteen chapters, while the Gospel according to St. John contains 21, that of St. Luke 24, and that of St. Matthew up to 28. It tends considerably toward brevity. And yet, how rich it is! But it is not a mere list of incidents dryly enumerated one after the other; these are events that unfold, as it were, before the reader's astonished eyes, so great is the precision of the details, so abundant is the vividness on every page. Thus, we have here a vivid photograph of the Savior. His human and divine personality is characterized in a striking way. Not only do we learn that he shared in all our infirmities, such as hunger, 11, 12, sleep, 4, 38, the desire for rest, 6, 31; that he was accessible to the feelings and passions of ordinary men, for example, that he could be saddened, 7, 34; 8, 12, love, 10, 21, feel pity, 6, 14, be astonished, 6, 61, be seized with indignation, 3, 5; 8, 12, 33; 10, 14; but we see him himself with his posture, 10, 32; 9, 35, his gesture, 8, 33; 9, 36; 10, 16, his looks, 3, 5, 34; 5, 32; 10, 23; 11, 11. We even hear his words spoken in his native tongue, 3, 17; 5, 41; 7, 34; 14, 6; and even the sighs that escaped from his breast, 7, 31; 8, 12. St. Mark also makes us witnesses of the striking expression that Our Lord Jesus Christ produced, whether on the crowd, 1, 22, 27; 2, 12; 6, 2, or on his disciples, 4, 40; 6, 51; 10, 24, 26, 32. He shows us the multitudes pressing around him, 3, 10; 5, 21, 31; 6, 33; sometimes so much so that he did not have time to eat, 3, 20; 6, 31. cf. 2:2; 3:32; 4:1. Among the Evangelists, no one has taken better care than he to note precisely the various circumstances of number, time, place, and people. 1. Circumstances of number: 5:13, "There were about two thousand of them, and they were drowned in the sea"; 6:7, "He began to send them out two by two"; 6:40, "And they sat down in groups of hundreds and fifties"; 14:30, "Before the rooster crows twice, you will deny me three times." 2. Circumstances of time: 1:35, "Early in the morning he got up"; 4:35, "That same day, when evening came, he said to them, 'Let us go over to the other side'"; 6:2, "When the Sabbath day came, he began to teach in the synagogue"; 11:11, "As it was already late, he went to Bethany"; 11:19, "When evening came, he left the city"; cf. 15:25; 16:2, etc. 3. The circumstances of place: 2:13, "Jesus went out again toward the sea"; 3:7, "Jesus withdrew with his disciples to the sea"; 4:1, "He began to teach again by the sea"; 5:20, "He went away and began to preach in the Decapolis"; cf. 7:31. 12:41, "Jesus sat down opposite the treasury"; 13:3, "they were sitting on the Mount of Olives opposite the temple"; 16:5, “And entering the tomb, they saw a young man sitting on the right side”; cf. 7:31; 14:68; 15:39, etc. 4. The circumstances of the persons: 1:29, “they came to the house of Simon and Andrew, with James and John”; 1:36, “Simon followed him, and those who were with him”; 3:22, “the scribes, who had come down from Jerusalem”; 13:3, “Peter, James, John, and Andrew asked him privately”; 15:21, “Simon of Cyrene, father of Alexander and Rufus”; cf. 3:6; 11:11; 11:21; 14:65, etc. We would almost have to transcribe the second Gospel verse by verse if we wanted to note all the details of this kind. If anyone wishes to know a Gospel event, not only its main points and general outlines, but also its most minute and vivid details, it is to St. Mark that they should turn. One can easily imagine the freshness, the interest, the dramatic flair that such a work must possess. We must add that it also has an extraordinary rapidity; for St. Mark does not take much trouble to connect the events he recounts. He does not group them, like St. Matthew, according to a logical order: he simply links them together, most often in historical order, with the formulas καὶ, πάλιν, εύθέως. This last expression recurs in his writing as many as 41 times (Fritzsche, Evangel. Marci, p. 44, is offended by it: "Words repeated to the point of nausea, and without any concern for style." Yet it is generally very effective and equivalent to the "Ecce" of St. Matthew). He flits from one incident to another, without taking the time to make historical reflections. The scene constantly changes in the most abrupt way before the reader's eyes.

Facts, and briefly recounted facts, such is the essence of the second Gospel. St. Mark, who is preeminently the evangelist of action, has not preserved in full any great discourse of the Savior (see in the commentary, the beginning of chapters 4 and 13); those of the words of the divine Master that he has inserted into his narrative are usually the most ardent, the most vivid, and he has been able, in summarizing them, to give them an incisive and energetic turn.

His style is simple, vigorous, precise, and generally full of clarity; yet it sometimes suffers from a certain obscurity, which arises from excessive concision. cf. 1, 13; 9, 5, 6; 4, 10, 34. We note there — 1° the frequent use of the present tense instead of the preterite: 1, 40, «A leper came to him»; 2, 3 (according to the Greek text), «some came, bringing him a paralytic»; 11, 1, «As they approached Jerusalem,… he sent two of his disciples»; 14, 43, «while he was still speaking, Judas Iscariot, one of the twelve, came»; cf. 2, 10, 17; 14, 66, etc.; — 2° Direct language instead of indirect language: 4:39, «He rebuked the wind and said to the sea, »Be still! Be quiet!«»; 5:9, «He asked it, »What is your name?«» 5:12, «And the demons begged him, saying, »Send us into the pigs«»; cf. 5:8; 6:23, 31; 9:25; 12:6; — 3° Emphatic repetition of the same thought: 1:45, «The man went away and began to tell and spread the story»; 3:26, «If Satan is divided against himself, he is divided and cannot stand, but his power will come to an end»; 4:8, «It produced fruit that grew up and increased»; 6, 25, "At once, she hurried back to the king"; 14, 68, "I don't know and I don't understand what you're saying," etc.; — 4° the accumulated negations: "you no longer let him do anything for his father or his mother," 7, 12; 9, 8; 12, 34; 15, 5; οὐϰέτι οὐ μὲ, 14, 25; «Let no one ever eat any fruit from you,» 11:14. — Besides the Latin and Aramaic expressions mentioned above, let us also note the following phrases, which St. Mark uses readily: ἀϰάθαρτον πνεῦμα eleven times, only six times in St. Matthew, three in St. Luke; ἤρξατο λέγειν, ϰράζειν, twenty-five times, the compounds of πορεύεσθαι: εἰσπορ eight times; ἐϰπορ eleven times; παραπορ four times; ἐπερωτάω, twenty‑five times; ϰηρύσσειν, fourteen times; the diminutives, vg θυγατρίον, ϰυνάρια, ϰοράσιον, ὠτάριον; certain little-used words, such as xœyxinohtç, ϰωμόπολις, ἀλαλάζειν, μεγιστᾶνες, νουνεχῶς, πλοιάριον, τρυμαλία, etc.

In its content, style, and treatment of subjects, the Gospel of St. Mark is essentially a copy made from a living image. The course and outcome of events are depicted with the most vivid outlines. Even if no other argument could be found to refute what has been said concerning the mythical origin of the Gospels, this lively and simple narrative, marked by the most perfect independence and originality, without connection to the symbolism of the Old Covenant, and devoid of the profound reasoning of the New, would suffice to refute this subversive theory. The details, which were originally intended for the vigorous intellect of Roman readers, are still full of instruction for us (See M. Bougaud, pp. 75, 76, and 82).

PLAN AND DIVISION.

1. St. Mark's plan is simple: it consists of following step by step the historical catechesis which, as we have seen (§ 4, no. 2), was to form the basis of his work. Now, this catechesis generally only encompassed the public life of Our Lord Jesus Christ from his baptism onward, with the preaching of John the Baptist as a preamble, and the Resurrection and the Ascension of the Savior as a conclusion (cf. Acts of the Apostles 1:21-22; 10:37-38; 13:23-25), and these are precisely the main lines followed by our evangelist. He therefore omits entirely the details relating to the Childhood and Hidden Life of Jesus, in order to immediately convey to the reader the voice and the austere precepts of the Forerunner. For him, as for the other Synoptic Gospels, the public Life of Christ is limited to the ministry exercised by Our Lord in Galilee; but, instead of stopping with them at the scenes of the ResurrectionHe follows the divine Master to His Ascension, to the splendors of Heaven, compensating, by this blessed addition to the glorious Life, for what He had omitted in the hidden Life. Jesus, as depicted in the second Gospel, is the Mighty God foretold by Isaiah 9:6, the victorious lion of the tribe of Judah spoken of in Revelation 5:5. In St. Mark's narrative, he finds a perpetual succession of forward and backward movements, of charges and retreats, as he calls them, which are not without analogy to the lion's march. Jesus advances vigorously against his enemies; then suddenly he withdraws to carry off the spoils of war or to prepare for a new charge. In the analytical table that concludes the Preface, we will highlight these varied and fascinating movements.

2. We have divided St. Mark's account into three parts, corresponding to the Public Life, the Suffering Life, and the Glorious Life of Our Lord Jesus Christ. The first part, 1:14–10:52, recounts Jesus' ministry from his messianic consecration until his arrival in Jerusalem for the Last Passover. It is preceded by a short preamble, 1:1–13, in which the Forerunner and the Messiah make their appearances in turn on the Gospel stage. It is subdivided into three sections, which show us Jesus Christ acting first in eastern Galilee, 1:14–7:23, then in northern Galilee, 7:24–9:50, and finally in Perea and on the road to Jerusalem, 10:1–52. In the second part, 11:1–15:57, we follow day by day the events of the last week of the Savior's life. The third, 16:1–20, will present for our admiration the glorious mysteries of his Resurrection and Ascension.

THE PRINCIPAL COMMENTATORS ON THE SECOND GOSPEL

No Latin Father commented on the Gospel according to St. Mark before Bede the Venerable (the commentary published under the name of St. Jerome is not his). In the Greek Church, one must go back to the fifth century to find a writer who explained it; for the fourteen homilies "on Mark," reproduced in Latin among the works of St. John Chrysostom, are not authentic; Victor of Antioch is therefore the oldest interpreter of our Gospel (Βίϰτωρος ϰαί ἄλλων ἐξηγήσεις εὶς τὸ ϰατὰ Μάρϰον εὐαγγέλιον, edid. CF Matthaei, Mosq. Later, Theophylact and Euthymius commented on it in their great works on the New Testament.

In the Middle Ages, as in modern times, it was generally the same exegetes who undertook to comment on St. Mark and St. Matthew: their names will therefore be found at the end of the Preface to our commentary on the first Gospel. Suffice it to recall the names of Maldonat, Fr. Luc of Bruges, Noël Alexandre, Corneille de Lapierre, Dom Calmet, Bishop Mac Evilly, Doctors Reischl, Schegg and Bisping among the Catholics, and of Fritzsche, Meyer, J.P. Lange, Alford, and Abbott among the Protestants.

SYNOPTIC DIVISION OF THE GOSPEL ACCORDING TO ST. MARK

PREAMBLE. 1, 1-13.

1. — The Precursor. 1, 1-8.

2. — The Messiah. 1, 9-13.

a. The baptism of Jesus. 1, 9-11.

b. The temptation of Jesus. 1, 12-13.

PART ONE

PUBLIC LIFE OF OUR LORD JESUS CHRIST, 1, 14-10, 52.

1st SECTION – MINISTRY OF JESUS IN EASTERN GALILEE. 1, 14-7, 23.

1. — The beginnings of the Savior’s preaching. 1, 14-15.

2. — The first disciples of Jesus. 1, 16-20.

3. — A Day in the Life of the Savior. 1, 21-39.

a. Healing of a demoniac. 1, 21-28.

b. Healing of St. Peter's mother-in-law and other sick people. 1, 29-34.

c. Jesus' Retreat on the Shores of the Lake. Apostolic Journey to Galilee. 1, 35-39.

4. — Healing of a leper, Retreat to deserted places. 1, 10-15.

5. — Jesus’ first conflicts with the Pharisees and the Scribes. 2, 1-3, 6.

a. The paralytic and the power to forgive sins. 2, 1-12.

b. The Calling of St. Matthew. 2:13-22.

c. The apostles violate the Sabbath rest. 2:23-28.

d. Healing of a withered hand. 3, 1-6.

6. — Jesus withdraws again to the shores of the Sea of Galilee. 3, 7-12.

7. — The Twelve Apostles. 3, 13-19.

8. — Men and their various attitudes towards Jesus. 3, 20-35.

a. The parents of Christ according to the flesh. 3, 20 and 21.

b. The Scribes accuse Jesus of colluding with Beelzebub. 3, 22-30.

c. The parents of Christ according to the spirit. 3, 31-35.

9. — The parables of the kingdom of heaven. 4, 1-34.

a. Parable of the Sower. 4:1-9.

b. Why parabolas? 4, 10-12.

c. Explanation of the parable of the sower. 4, 13-20.

d. We must listen carefully to the word of God. 4:21-25.

e. Parable of the Wheat Field. 4, 26-29.

f. Parable of the mustard seed. 4, 30-32.

g. Other parables of Jesus. 4, 33-34.

10. — The storm calmed. 4, 35-40.

11. — The Demoniac of Gadara. 5, 1-20.

12. — Jairus' daughter and the woman with the hemorrhage. 5, 21-43.

13. — Jesus rejected, despised in Nazareth, retreats to the neighboring towns. 6, 1-6.

11. — Mission of the Twelve. 6, 7-13.

15. — The Martyrdom of St. John the Baptist. 6, 14-29.

16. — Retreat in a deserted place, and the first multiplication of the loaves. 6, 30-44.

17. — Jesus walks on water. 6, 45-52.

18. — Miracles of healing in the plain of Gennesaret. 6, 53-56.

19. — Conflict with the Pharisees concerning purity and impurity. 7, 1-23.

2nd SECTION. — MINISTRY OF JESUS IN WESTERN AND NORTHERN GALILEE. 7, 24-10, 49.

1 — Jesus withdrew to the Phoenician region., and healed the Canaanite woman's daughter. 7, 24-30.

2. — Cure of a deaf-mute. 7, 31-37.

3. — Second multiplication of the loaves. 8, 1-9.

4. — The sign from heaven and the leaven of the Pharisees. 8, 10-21.

5. — Healing of a blind man at Bethsaida. 8, 22-26.

6. — Jesus withdrew to Caesarea Philippi. Confession of St. Peter. 8, 27-30.

7. — The cross for Christ and for Christians. 8, 31-39.

8. — The Transfiguration. 9, 1-12.

a. The miracle. 9, 1-7.

b. Memorable conversation which is connected with the miracle. 9, 8-12.

9. — Cure of a lunatic. 9, 13-28.

10. — The Passion predicted for the second time. 9, 29-31.

11. — Some serious lessons. 9, 32-49.

a. Lesson inhumility. 9, 32-36.

b. Lesson in tolerance. 9, 37-40.

c. Lesson concerning the scandal. 9, 41-49.

3rd SECTION. JESUS IN PEREA AND ON THE ROAD TO JERUSALEM. 9, 1-52.

1. — The Christianity and the family. 10, 1-16.

a. Christian marriage, 10, 1-1 2.

b. Young children. 10, 13-16.

2. ‑ The Christianity and riches, 10, 17-31.

a. The Lesson of Facts. 10, 17-22.

b. The lesson in words. 10, 23-31.

3. — The Passion is predicted for the third time. 10, 32-34.

4. — Ambition of the sons of Zebedee. 10, 35-45.

5. — The blind man of Jericho. 10, 46-52.

PART TWO

THE LAST DAYS AND THE PASSION OF JESUS. 11-15.

I. Jesus' triumphant entry into Jerusalem, and retreat to Bethany. 11, 1-11.

II. The Messianic Judge. 11, 12–13, 37.

1. — The cursed fig tree. 11, 12-14.

2. — Expulsion of vendors and retreat in Bethany. 11, 15-19.

3. — The power of faith. 11, 20-26.

4. — Christ victorious over his enemies. 11, 27-12,40.

a. Where did Jesus' powers come from? 11:27-33

b. Parable of the murderous tenants. 12:1-12

c. God and Caesar. 12, 13-17.

d. The resurrection of the dead. 12, 18-27.

e. What is the first commandment? 12:28-34

f. The Messiah and David. 12, 35-37.

g. «Beware of the Scribes.» 12, 38-40.

5. — The widow's mite. 12, 41-44.

6. — The eschatological discourse. 13,1-37.

a. Occasion of the speech. 13, 1-4.

b. First part of the discourse: the Prophecy. 13, 5-31.

c. Second part: Exhortation to virtue. 13, 32-37.

III. «"The Suffering Christ"». 14 and 15.

1. — Conspiracy of the Sanhedrin. 14, 1 and 2.

2. — The meal and the anointing at Bethany. 14, 3-9.

3. — Judas's shameful bargain. 14, 10-11.

4. — The Last Supper. 14, 12-25.

a. Preparations for the Passover feast. 14, 12-16.

b. Legal Last Supper. 14, 17-21.

c. Eucharistic Supper. 14, 22-25.

5. — Three predictions. 14, 26-31.

6. — Gethsemane. 14, 32-42.

7. — The arrest. 14, 43-52.

8. — Jesus before the Sanhedrin. 14, 53-65.

9. — The triple denial of St. Peter. 14, 66-72.

10. — Jesus judged and condemned by Pilate, 15, 1-15.

a. Jesus is handed over to the Romans. 15, 1.

b. Jesus questioned by Pilate. 15. 2-5.

c. Jesus and Barabbas. 15, 6-15.

11. — Jesus outraged in the praetorium. 15, 16-19.

12. — The Stations of the Cross. 15, 20-22.

13.— Crucifixion, agony and death of Jesus. 15, 23-37.

11.— What immediately followed the death of Jesus. 15, 38-41.

15. — The burial of Jesus. 15, 42-47.

PART THREE

1. — The Risen Christ. 16, 1-18.

a. The holy women at the tomb. 16, 1-8.

b. Jesus appears to Mary Magdalene. 16, 9-11.

c. He appears to two disciples. 16, 12-13.

d. He appears to the Apostles. 16, 14.

2. — Christ ascending into heaven. 16, 15-20.

a. Commands given to the Apostles. 16, 15-18.

b. The Ascension of Our Lord Jesus Christ. 16, 19-20.