Gospel of Jesus Christ according to Saint Matthew

At that time, Jesus came to the Sea of Galilee. He went up on a mountainside and sat down. Large crowds came to him, bringing the lame, the blind, the disabled, the mute, and many others; they placed them before him, and he healed them. The crowds were amazed when they saw the mute speaking, the disabled made whole, the lame walking, and the blind seeing; and they glorified the God of Israel.

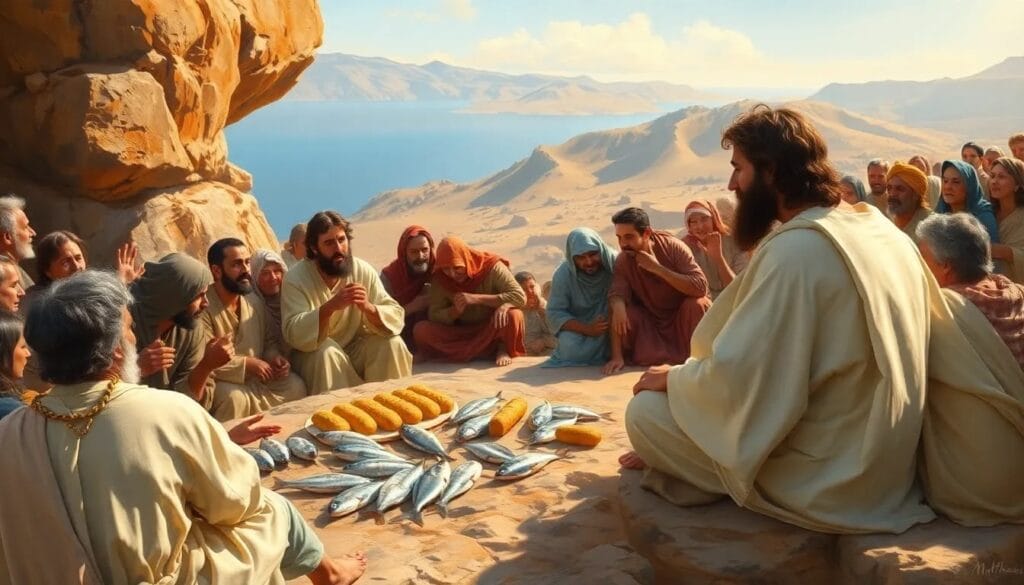

Jesus called his disciples to him and said, «My heart goes out to these people, because they have already been with me three days and have nothing to eat. I do not want to send them away without them eating, or they will become weak on the way.» The disciples answered him, «Where could we get enough bread in this remote place to feed such a crowd?» «How many loaves do you have?» he asked. «Seven,» they replied, “and a few small fish.”

Then he invited the crowd to sit down on the ground. He took the seven loaves and the fish, and after giving thanks, he broke them and distributed them to the disciples, and the disciples to the crowd. They all ate and were satisfied. The disciples gathered up seven baskets full of leftovers.

When Jesus restores the whole human being: healing and shared bread

How compassion Divine responds to our physical and spiritual needs by inviting us to participate in its work of complete restoration..

On a mountaintop near the Sea of Galilee, Jesus performed acts that revealed the very heart of God: he healed broken bodies and fed hungry stomachs. This passage from Matthew shows us a Savior who never separates body from soul, who sees the person in their entirety. It invites us to discover how compassion The divine is concretely embodied in our lives and how we are called, like the disciples, to actively participate in this work of restoration.

The fundamental nature of compassion of Christ who embraces all our human dimensions • The stages by which Jesus restores us and leads us from mere survival to abundance • How to become active agents of this transformative compassion in our daily lives • Concrete practices for cultivating an integral vision of the human person

When the mountain becomes a place of grace

The geographical and liturgical setting of the narrative

Matthew places this scene near the Sea of Galilee, on a mountain. This geographical detail is never insignificant in the Gospel. The mountain immediately evokes other key moments: Mount Sinai where Moses received the Law, the Mount of Beatitudes where Jesus proclaimed the new order of the Kingdom. Here, Jesus sits, in the posture of a teacher, but his teaching will not be merely words.

The liturgical context of this text is also revealing. It is proclaimed during Advent, This period of waiting and preparation for the coming of the Messiah is called the Alleluia antiphon. It tells us: «The Lord will come to save his people. Blessed are those who are ready to go out to meet him.» These words create a framework for active waiting. They remind us that salvation is not a distant abstraction but a presence that comes to us, that draws near to our concrete human condition.

The Sea of Galilee, with its shores familiar to the first disciples, becomes the setting for a gradual revelation. Jesus does not hide in a temple or an institutional sacred place. He makes himself accessible on a mountain near a place of everyday life. This geographical accessibility reflects a fundamental spiritual accessibility: the Kingdom of God is not reserved for the initiated but is open to all who come with their misery.

The large crowds mentioned by Matthew suggest a rumor spreading, a hope taking root. They speak of a man who heals, who listens, who turns no one away. This reputation attracts not only isolated individuals but entire groups bringing their sick. One can imagine the dusty roads, the makeshift stretchers, the hope mingled with exhaustion. These crowds represent humanity in its universal quest for healing and meaning.

This story takes place after several controversies with the Pharisees concerning traditions and ritual purity. Jesus has just proclaimed that what makes someone impure comes not from the outside but from the heart. Now, he demonstrates by his actions that true purity consists of touching the untouchable, restoring the outcast, and feeding the hungry. Teaching and action are one.

The divine logic of complete restoration

Deciphering the structure and central message of the passage

This biblical text unfolds according to a precise theological architecture in two complementary movements which reveal Jesus' holistic vision concerning human salvation.

The first movement presents a scene of mass healings. Large crowds "approach" Jesus, a verb which in the Gospel of Matthew often evokes an act of faith. People do not come to Jesus by chance or out of idle curiosity, but driven by expectation, by a thirst. These crowds bring "the lame, the blind, the crippled, the mute, and many others." This list is not simply a medical inventory: it evokes the prophecies of Isaiah concerning the Messianic era. "Then the eyes of the blind will be opened, and the ears of the deaf unstopped. Then the lame will leap like a deer, and the tongue of the mute will shout for joy" (Isaiah 35:5-6).

The detail "they were laid at his feet" reveals a posture of«humility and complete trust. These sick people are supported by others, a sign of community solidarity in times of hardship. Jesus doesn't ask for any prior act of faith, doesn't impose any conditions: "he healed them," period. The action is as simple as it is radical. Compassion Divine does not negotiate, it acts.

The reaction of the crowd, which "gave glory to the God of Israel," is theologically crucial. The miracles of Jesus These are not spectacles intended for his own glorification, but signs pointing toward the Father. This spontaneous doxology shows that creation, freed from its constraints, naturally resumes its movement toward the Creator. Healing is not an end in itself, but a means of restoring the primal relationship between humanity and God.

The second movement introduces a shift in perspective. After three days spent with Jesus, the crowd finds itself in a precarious situation: no food in the desert. Jesus then takes the initiative: «I am filled with compassion.» The Greek uses the verb «splanchnizomai,» which literally evokes a profound upheaval of the innermost being, a visceral emotion. This compassion is not a superficial feeling but a deep stirring of Jesus’ entire being in the face of human suffering.

The disciples' protest ("Where in this desert can we find enough bread?") expresses a reasonable human logic: in a place of scarcity, how can such a crowd be fed? But Jesus doesn't start with what is lacking; he starts with what is available: "How many loaves do you have?" Seven loaves and a few fish. A paltry portion compared to the needs, but sufficient in the hands of Christ.

The gestures that follow – taking, giving thanks, breaking, giving – anticipate the Last Supper and the Eucharist. It is no coincidence that Matthew uses this precise liturgical vocabulary. The multiplication of the loaves is not merely a social miracle but a sacramental sign. It proclaims that Jesus is the living bread that nourishes deeply, that satisfies beyond measure. hunger physical.

The result exceeded expectations: «They all ate and were satisfied,» and seven baskets were left over. The number seven symbolizes fullness in Jewish culture. God's abundance cannot be measured by our calculations of scarcity. Where we see insufficiency, God sees potential abundance.

Three dimensions of compassion in action

Physical restoration as the first act of love

The first dimension revealed by this text is Jesus' attention to immediate bodily suffering. Too often in the history of Christian spirituality, the soul and the body have been opposed, one valued at the expense of the other. This Gospel account dismantles this false dichotomy.

Jesus doesn't tell the sick, "Your physical suffering doesn't matter; only your spiritual salvation counts." On the contrary, he begins by addressing their most painful physical reality. He understands that a suffering body prevents the flourishing of all other dimensions of the person. How can one pray when pain is unbearable? How can one love one's neighbor when trapped in the isolation caused by disability?

The healings performed by Jesus are not magical feats but acts of restoration of the human dignity. In first-century Jewish society, these infirmities often led to social and religious exclusion. The lame could not fully participate in pilgrimages, the mute could not recite communal prayers, and the blind were often considered to be under a divine curse. By healing these people, Jesus did more than simply repair bodies: he reintegrated outcasts into the human and religious community.

For us today, this dimension reminds us that Christian commitment cannot ignore the material and physical needs of people. A Christian who neglects hunger, To prioritize illness and precarious living conditions in the name of a supposed "spiritual" priority would betray the example of Christ. The Gospel is incarnate, or it is not.

In concrete terms, this translates into supporting healthcare systems, accompanying the sick, and involvement in social welfare organizations. But also, on a more personal level, into simply paying attention to the body of another: noticing a colleague's fatigue, offering a meal to an isolated neighbor, taking the time to listen to an elderly person's physical complaints without dismissing them out of hand.

Community catering as a place of shared healing

The second dimension revealed by this passage is the importance of the community dimension in the work of healing. Jesus does not meet these sick people in private and discreet consultations. He heals them in the midst of "large crowds", under the gaze of all.

This publicity surrounding the miracle has several meanings. First, it demonstrates that healing is never just an individual matter. When someone regains their health, it is an entire community that is restored. The lame man who walks again represents a son who can once more work for his family, a father who can reclaim his place, a member who is fully reintegrated into their community. The healing of one person benefits many.

Furthermore, the fact that "they laid them at his feet" underscores the active role of those around them. These sick people do not arrive alone before Jesus. They are carried, accompanied, and presented by others. This narrative detail reveals a profound spiritual truth: we need one another to access the source of healing. Sometimes, when we ourselves are broken, exhausted, and discouraged, it is others who must carry us to Christ. And conversely, we are called to be those who carry those who no longer have the strength to walk alone.

This insight finds a powerful echo in the multiplication of the loaves. Jesus does not make the bread appear directly in the hands of each hungry person. He works through the disciples: "He gave them to the disciples, and the disciples to the crowds." The chain of distribution itself becomes a communal act, a collective participation in the miracle. Each disciple becomes a necessary link in the transmission of the divine gift.

For our contemporary Christian communities, this model challenges our organization and priorities. Are we places where we can "lay down" our burdens, our suffering, our infirmities without being judged? Have we created spaces where solidarity can be expressed concretely? Or have we favored a spirituality so individualized that each person remains alone with their wounds?

The ancient practice of intercession takes on its full meaning here. To pray for a sick person is to "bring" them before Christ, to play this role of benevolent mediator. But intercession cannot remain merely verbal: it must be embodied in visits, services rendered, and faithful presence.

Spiritual restoration as the ultimate goal

The third and deepest dimension concerns the restoration of the relationship between humanity and God. This dimension is evident in the reaction of the crowd, who "glorified the God of Israel." The physical miracle becomes a spiritual revelation.

The prophets of the Old Testament foretold that the Messianic era would be characterized by a comprehensive restoration affecting the body, society, and the relationship with God. Isaiah described a transformed world where "all creation" would participate in this renewal. Jesus fulfills these promises not in some distant and abstract future, but here and now, on this mountain by the Sea of Galilee.

The multiplication of the loaves takes this spiritual dimension to a higher level. By taking the bread, giving thanks, breaking it, and giving it away, Jesus foreshadows the Eucharist. It signifies that his own life will be "broken" and "given" for the multitude. The physical bread becomes a sign of the spiritual bread, of that food which gives eternal life.

Saint John, in his Gospel, elaborates at length on this theology of the bread of life after the parallel account of the multiplication of the loaves: «I am the living bread that came down from heaven. If anyone eats of this bread, he will live forever» (John 6:51). Matthew, more restrained, leaves the connection to the attentive reader, but it is undeniably present.

This spiritual dimension does not come "after" the first two as an optional addition. It permeates and transfigures them from within. Jesus heals bodies because he sees in each person a being called to communion with God. He feeds hungry bellies because he recognizes in each person a deeper hunger, a thirst for the infinite that only God can satisfy.

For the modern believer, this threefold dimension of compassion Christ's faith becomes a way of life. Our faith cannot be limited to pious sentiments or ritual practices disconnected from reality. It must be embodied in attentiveness to suffering bodies, in effective community solidarity, and in a constant openness to the transcendent dimension of human existence.

How to experience this restoration in our different spheres of existence

The teaching of this Gospel passage begins by transforming our view of ourselves. Too often, we internalize a form of dualism that leads us to despise our bodies, ignore our material needs, or, conversely, to become trapped by them, forgetting our spiritual dimension.

Jesus invites us to reconcile with ourselves. Accepting that we have physical needs is not a sign of spiritual weakness but a humble acknowledgment of our created condition. We are not disembodied angels, and to claim otherwise is pride rather than holiness. Taking care of our health, our food, and our rest is to respect the temple God has entrusted to us.

At the same time, recognizing that we also have a spiritual hunger, a need for meaning, beauty, and transcendence, is to honor the divine dimension within us, this image of God that we carry within us. Neglecting this dimension under the pretext of "realism" or "pragmatism" condemns us to an impoverished life, reduced to its mere horizontal dimension.

In practical terms, this means building a rhythm of life that integrates these different dimensions. Daily prayer times that nourish our souls. Meals eaten calmly and mindfully, honoring our bodies. Moments of rest that acknowledge our limits. Authentic relationships that build our sense of community.

When we face health challenges, this passage encourages us not to excessively spiritualize our suffering («God sends me this cross to purify me») nor to despair over it («my body betrays me, I am worthless»). Jesus shows us a third way: to compassionately embrace our own fragility, to seek the necessary care while remaining open to what this ordeal may reveal about our deepest selves.

In our families and close relationships

Within our families, the central lesson of this gospel is learning to compassion concrete. Jesus doesn't just say "I sympathize with you," he acts. In our homes, how often do we remain at the level of good intentions without taking action?

A sick spouse needs actual medical care, not just attention. A child tired from a week of school needs their favorite meal prepared and time to relax, not just abstract acknowledgment of their stress. An elderly parent needs to be accompanied to medical appointments, not just receive sympathetic phone calls.

But the multiplication of the loaves also teaches us something about managing our family resources. The disciples saw the shortage: seven loaves for thousands of people. How often, in our families, do we start with what we lack rather than what we have? "We don't have enough money," "we don't have enough time," "we don't have enough patience.".

Jesus invites us to a change of perspective: to start with what is available, however little, and to place it at the service of all in trust. This limited availability, offered with generosity and trust in God, becomes a source of abundance. In concrete terms, this can mean opening one's table to a lonely neighbor even if the meal is simple, offering a few hours of babysitting to an exhausted couple even if one has little free time, sharing clothes that have become too small rather than accumulating them.

The model of the distribution chain is also valuable for family life. Jesus doesn't do everything alone; he involves his disciples. In a family, solidarity is built when each person, according to their abilities, participates in caring for others. Children can be introduced to this practice very early: bringing water to their grandmother, helping to set the table, comforting a crying brother or sister.

In our professional and social commitments

The world of work and social engagement is often perceived as a purely secular realm, disconnected from any spiritual concerns. This passage from the Gospel challenges this artificial separation.

If Jesus attends to the concrete physical needs of the crowds, it means that all work that contributes to people's material well-being has theological dignity. The doctor who heals, the teacher who educates, the baker who feeds, the craftsman who builds, the farmer who cultivates: all participate in their own way in this work of restoration begun by Christ.

This vision sanctifies the work daily life. It's not just about "earning a living" in a utilitarian sense, but about contributing to the common good, participating in God's creative and restorative work. This radically changes our motivation for work and the way we carry it out.

In the social and political sphere, this text establishes an ethic of solidarity. Public health systems, food aid policies, and support programs for people with disabilities are not simply "nice" options but expressions of this Christ-like compassion within the social order. A Christian cannot remain indifferent to structures that exclude, impoverish, or dehumanize.

But we must be careful not to fall into a purely technocratic approach. Jesus doesn't primarily create an institution; he establishes a personal relationship. Structures are necessary but insufficient. We also need this dimension of closeness, of looking into the other person's face, of listening to their unique story. Volunteers in charitable organizations, caregivers who take the time to listen, social workers who truly consider the individual: all embody this dual requirement of structural efficiency and personal compassion.

When the Church Fathers encounter this word

Patristic readings and their enduring relevance

The Church Fathers, those great thinkers and pastors of the early Christian centuries, meditated extensively on the accounts of healing and the multiplication of the loaves. Their interpretations, far from being mere historical curiosities, still illuminate our understanding of the text.

Saint John Chrysostom, this flamboyant 4th-century preacher, insisted on compassion Jesus as the primary motivation for miracles. For him, Christ does not seek to impress with his power but to bring relief through his love. In his homilies on Matthew, Chrysostom emphasizes that Jesus waited three days before feeding the crowd, not out of negligence, but so that the need would become evident and the solution would clearly appear supernatural. This divine patience is not indifference but pedagogy: God sometimes allows us to experience our poverty so that we may more clearly recognize his providence.

Saint Augustine, He, for his part, develops a more symbolic interpretation. For him, the seven loaves represent the fullness of the Spirit (the number seven symbolizing perfection). The few fish evoke the writings of the prophets (fish being a symbol of the early Christians who were persecuted). The multiplication then signifies that the Holy Spirit unfolds the Word of God through the Scriptures to spiritually nourish the multitude of believers. This allegorical reading does not negate the literal meaning but enriches it with an additional dimension.

Saint Cyril of Alexandria emphasizes the role of the disciples in distributing the bread. He sees in this an image of the Church's mission: to receive from Christ and to transmit to the faithful. The disciples do not create the bread; they only distribute it. Similarly, priests and bishops are not the owners of grace but servants and distributors of gifts that come from elsewhere.

The liturgical and sacramental tradition

Christian liturgy, in its wisdom accumulated over the centuries, has deeply integrated the symbolism of this story. The Eucharist It itself echoes the four gestures of Jesus: taking, giving thanks, breaking, giving. Each Eucharistic celebration re-enacts this initial multiplication.

But more broadly, the sacramental tradition of the Church recognizes in the actions of Christ a model for all the sacraments. Baptism "heals" the soul of original sin. Confirmation "nourishes" the believer with the strength of the Spirit. Reconciliation "restores" the sinner to full communion. The anointing of the sick "heals" the body and soul in the ordeal of illness. Each sacrament, in its own way, participates in this work of the integral restoration of humanity begun by Jesus on that mountain in Galilee.

Monastic tradition has particularly reflected on the desert as a place of multiplication. The great founders of monasticism, from Saint Anthony to Saint Benedict, They went to the desert not to flee the world, but to encounter God in a more radical way. They discovered that where there is nothing according to human standards, God can give everything. Benedictine rule, which still structures the lives of thousands of monks and nuns today, emphasizes the’hospitality : to receive the guest as Christ himself, to share the little that one has in trust.

Contemporary theological scope

Contemporary theologians have explored some of the insights present in this text. Hans Urs von Balthasar, a major 20th-century thinker, developed a theology of love as a response to the need for the other. For him, compassion Christ is not a passing emotion but the very expression of the triune nature of God: a God who is relationship, gift, going out of oneself towards the other.

Liberation theology, which originated in Latin America, has strongly emphasized the social and political dimension of this type of narrative. Gustavo Gutiérrez insists that Jesus does not spiritualize. hunger He provides food. This reading is a timely reminder that the Gospel cannot be reduced to an individualistic message of salvation. It includes a demand for the transformation of the social structures that produce hunger, illness and exclusion.

Jean Vanier, founder of L'Arche and a contemporary prophet of the inclusion of people with disabilities, lived and taught that "disability" can become a privileged place for the revelation of Christ's presence. In the tradition of this Gospel passage, he showed that people with disabilities are not primarily objects of charity but subjects who evangelize us through their embraced vulnerability. They teach us to receive before giving, to be transformed by the relationship before seeking to transform the other.

Concrete steps on the path of compassion

First step: cultivate the gaze that truly sees

Compassion begins with sight. Jesus "sees" the lame, the blind, the cripples. He does not look away, does not minimize their suffering, does not walk on by. This gaze is not that of the voyeur who morbidly dwells on the misery of others, but that of the Good Samaritan who "sees and is moved with compassion.".

In practical terms, this means slowing down our frantic pace to truly observe our surroundings. On the subway, instead of remaining absorbed by our phones, looking up and noticing the elderly person struggling to stay upright. In our neighborhood, recognizing the face of the man sleeping on the street rather than ignoring him out of embarrassment or habit. At work, perceiving signs of fatigue or distress in a colleague.

This contemplative gaze upon others can be cultivated through prayer. Taking a few minutes each evening to mentally review the faces encountered during the day, offering them to God, and asking for divine blessing for each one. This practice gradually refines our sensitivity and makes us more attentive to daily life.

Second step: allowing oneself to be moved by compassion

Seeing is not enough. Jesus is "moved with compassion," literally "moved to his core." This profound emotion is not a weakness but a strength. It pulls us out of our indifference and sets us in motion.

Many of us have learned to protect ourselves emotionally from the suffering in the world. It's an understandable defense mechanism: we can't bear the weight of all humanity's misery. But there's a difference between protecting ourselves in a healthy way and becoming completely hardened. Jesus shows us that we can be deeply moved by suffering without being crushed by it, because we bear it in trust in the Father.

To cultivate this compassion, we can practice active listening. When someone tells us about their difficulties, resist the temptation to minimize them ("it's not that bad"), to moralize ("you should have done things differently"), or to compare ourselves ("I've been through worse"). Simply welcome the other person's suffering, acknowledge it, and validate it. Sometimes, this compassionate listening is itself an act of healing.

Third step: moving from emotion to concrete action

Compassion Christ's compassion never remains at the level of emotion. It is immediately translated into actions: he heals, he nourishes. Similarly, our compassion must be embodied.

The action can be very simple: preparing a meal for a sick neighbor, offering our seat seat In terms of transportation, we can give a few hours of our time to a local association. It's not about embarking on projects beyond our capabilities, but about doing what's within our reach, with our seven loaves of bread and a few fish.

One pitfall to avoid is excessive activism that compensates for a lack of genuine connection. Jesus doesn't simply organize an efficient distribution of food. He gives thanks, he establishes a relationship with the Father, he involves the disciples in a communal process. Our actions must remain rooted in prayer and a personal relationship with God and others.

Fourth step: learning to receive as much as to give

This passage also shows us the importance of knowing how to receive. The sick They allow themselves to be "placed" at Jesus' feet. The disciples receive the bread from Jesus' hands before distributing it. No one is solely a giver or solely a receiver.

In our lives, accepting that we need help, support, and a listening ear is sometimes harder than giving. It requires acknowledging our vulnerability and our dependence. But it is precisely this acceptance of our poverty which makes us capable of true compassion. Those who never acknowledge their own needs quickly become condescending in their help to others.

In practical terms, this means daring to ask for help when facing a difficult situation, accepting a friend's invitation, and simply saying thank you for services rendered. It allows others to, in turn, adopt the posture of Christ who gives and serves.

When the message encounters our modern resistance

The challenge of efficiency versus the logic of giving

Our modern society is obsessed with efficiency, profitability, and measurable results. In this context, the story of the multiplication of the loaves may seem naive or unrealistic. Seven loaves for thousands of people? No reasonable business plan would validate such an equation.

Yet, the Gospel confronts us with a different logic: that of the free gift which multiplies through sharing. It is not the initial quantity that counts, but the disposition of the heart that offers all it has. This logic defies our rational calculations and invites us to a trust that may seem foolish.

In our everyday lives, this translates into the courage to give even when "it doesn't seem reasonable." It means agreeing to take time for someone when we already have a packed schedule. It means donating financially to a cause when we ourselves are struggling to make ends meet. It means committing to volunteer work when we already feel exhausted.

This logic of giving does not imply recklessness or irresponsibility. Jesus does not ask his disciples to throw themselves into the void. He asks them what they have, and then works from there. It is about putting our limited resources at the service of God and neighbor, with the confidence that this will bear fruit beyond our expectations.

The challenge of immediacy and patience

Our culture of instant gratification demands immediate results and quick solutions. We are accustomed to ordering online and receiving next-day delivery, accessing information with a few clicks, and solving problems with an app.

However, this passage shows us a Jesus who takes his time. The crowds remain with him for "three days" before he feeds them. He doesn't rush. He lets the need deepen., hunger to make itself felt. This divine patience is not insensitivity but a pedagogy: it creates the space for gratitude to emerge, for the miracle to be recognized as such.

In our compassionate commitments, we must accept that healing, restoration, and transformation take time. Accompanying someone through illness, supporting a young person in difficulty, helping someone escape poverty: these are long processes, with progress and setbacks. Patience becomes a cardinal virtue of compassion.

But this patience should not be used as an excuse for inaction. Jesus is patient, but he also acts decisively when the time is right. There is a time to wait and a time to intervene, and discerning between the two requires wisdom and prayer.

The challenge of individualism and the community dimension

Our era values individual autonomy to the point of isolation. Everyone is expected to fend for themselves, manage their own problems, and not "bother" others. This mentality is the complete opposite of what our text demonstrates.

The sick They are "placed" by others. They depend on the solidarity of those around them to access the source of healing. This interdependence is not presented as a weakness but as the normal reality of the human condition. We need each other.

Our challenge is to create or recreate effective networks of solidarity. In our parishes, our neighborhoods, our buildings, do we know our neighbors? Have we forged bonds strong enough that in times of hardship, there is someone to turn to?

In practical terms, it can start very simply: organizing a potluck meal in your building, creating a neighborhood WhatsApp group to help each other, systematically offering help to newcomers. These small gestures gradually build a social fabric that can support everyone through difficult times.

The challenge of the temptation of the spectacular

In a world saturated with sensational images, we risk retaining only... miracles of Jesus than their extraordinary aspect. We marvel at the multiplication, but we forget the simple gesture of taking what is available and giving thanks.

The spectacular is not the essential thing. The essential thing is the quality of the relationship, the attention paid to the other person, in loyalty daily. Miraculous healings are rare. Patiently accompanying a chronically ill person is commonplace but just as precious in the eyes of God.

We must resist the temptation to value only spectacular actions, visible projects, and quantifiable results. True compassion is often found in the shadows, in small gestures repeated day after day, in loyalty discreet, making no noise but weaving a loving and reliable presence.

When our lips meet the heart of God

Lord Jesus, you who on the mountain welcomed the crowds with their sufferings and their needs,

Open my eyes so that I can truly see those around me.,

their tired bodies, their wounded hearts, their thirsty souls.

Give me that gaze that does not judge, that does not look away,

but who contemplates in each person your precious image, even damaged.

Remove from my heart the indifference that protects me from the suffering of others,

the fear that paralyzes me in the face of the magnitude of the needs,

the calculation which first measures what it will cost me to give.

Seize my very core with your divine compassion,

that overwhelming tenderness that drove you to heal, to nourish, to lift up.

Prayer of recognition and gratitude

Heavenly Father, I thank you for all the times you have healed me,

not only in my body, but also in my heart and mind.

To the people you placed in my path who carried me when I no longer had the strength to move forward,

for the hands that cared for me, the voices that comforted me, the presences that supported me.

Thank you for the daily bread you so faithfully provide me.,

this physical nourishment that keeps my body alive,

but above all for the living bread of your Word and of your Eucharist that nourishes my soul.

Thank you for the seven loaves of bread and the few fish I have.,

these limited resources that you can multiply beyond my expectations

when I confidently place them in your hands.

Prayer of intercession for those who suffer

Christ the Savior, I now present to you all those whose bodies suffer:

the sick in hospitals awaiting recovery,

disabled people who struggle every day against obstacles and the way others look at them,

elderly people whose tired bodies limit their autonomy,

children who are malformed or weakened from birth.

Place your compassionate gaze and your healing hand upon them.

Only where physical healing is not possible,

you grant peace inner strength, the strength of the soul, and hope that does not disappoint.

I present to you all those who are hungry:

the starving people in war-torn countries where food has become a weapon,

the vulnerable people in our wealthy cities who don't have enough to eat,

malnourished children whose development is compromised,

lonely people who eat a solitary meal without joy.

Multiply the bread on our tables and in our hearts,

that we learn sharing which creates abundance for all.

Prayer of commitment and sending forth

Holy Spirit, make me an instrument of your compassion.

Show me today one person whom I can "carry" to Christ through my prayer or action.

Give me the courage of my seven loaves, not to wait until I have a lot to start giving.

Teach me to give thanks for what I have rather than lamenting what I lack.

Help me to break away and share, that is, to accept that my resources are fragmented, distributed, multiplied in giving.

Make me understand that I'm just a link in your distribution chain.,

that I receive from above to pass on to those around me.,

that my true wealth lies in this circulation of giving, not in accumulation.

My daily work, however modest,

contribute to this work of restoration that you began in Jesus Christ

and that you continue through your Church and all men and women of goodwill.

May my hands become your hands for healing.,

my voice, your voice, to comfort,

My presence, your presence, to accompany you.

And when I myself am broken, hungry, exhausted,

give me the’humility to allow myself to be laid at the feet of Christ,

supported by my brothers and sisters,

confident that you can lift me up and restore me in turn.

Amen.

Towards a life transformed by compassion

This text from Matthew reveals to us a God who never separates the body from the soul, the social justice of personal holiness, immediate action and profound transformation. Jesus heals and nourishes because he sees in each person a unique being, created in the image of God, called to the fullness of life.

The mountain by the Sea of Galilee is not a distant, mythical place. It is our concrete world, with its real suffering and pressing needs. Jesus continues to sit there, welcoming crowds, healing and feeding. But now he does it through us, his disciples. We have become that distribution chain: receiving from Christ and passing it on to the multitudes.

This vocation is both demanding and liberating. Demanding because it takes us out of our comfort zone, confronts us with the suffering of others, and asks us to give what we have without calculating the cost. Liberating because it takes us beyond ourselves, connects us to something greater than ourselves, and allows us to experience the profound joy that arises from authentic giving.

The world today, with its glaring inequalities, its millions of migrants, The world's epidemics and climate crises may seem overwhelming, the needs too immense. We risk becoming discouraged before we even begin, like the disciples faced with the hungry crowd. But Jesus doesn't ask us to solve all the world's problems. He asks us, "How many loaves do you have?" What is your particular skill? How much time can you offer? What relationship can you cultivate? What gift can you share?

Starting from there, with confidence, giving thanks, and letting God multiply. That's the whole difference between exhausting activism that drains us and action rooted in prayer that nourishes us by nourishing others. Between the social program that treats people like statistics and compassion evangelical, which meets each person in their uniqueness.

Some practices to move forward

• Begin each day with a prayer of availability: "Lord, show me today whom I can serve" and remain attentive to opportunities that arise, often in unexpected ways.

• To engage concretely in at least one regular service action: weekly volunteering in a charitable association, regular visits to an isolated person, participation in a neighborhood mutual aid network.

• Practice’hospitality by opening his table once a month to someone who is lonely, new to the neighborhood, or going through a difficult time, thus creating spaces for sharing and communion.

• Cultivate a contemplative gaze by taking five minutes each evening to mentally review the faces encountered during the day and pray for them, gradually refining our sensitivity to the needs of others.

• Learning to ask for help when you need it yourself, recognizing your own vulnerability and allowing others to exercise compassion towards you.

• Develop one's social judgment by researching the structural causes of poverty, of exclusion and suffering, so that our individual compassion is linked to a commitment to greater justice.

• Actively participate in the Eucharist Sunday, recognizing in it the sacramental extension of this multiplication of the loaves, source and summit of all authentic Christian life.

Some resources for further exploration

Benedict XVI, Deus Caritas Est, encyclical on the’Christian love which develops the relationship between charity and social justice (2005).

François, Fratelli Tutti, encyclical on brotherhood and social friendship, developing an ethic of universal care (2020).

Hans Urs von Balthasar, Love alone is worthy of faith, major theological reflection on divine agape and its implications (Aubier, 1966).

Jean Vanier, The community, a place of forgiveness and celebration, testimony and reflection on community life with disabled people (Fleurus, 1989).

Saint John Chrysostom, Homilies on the Gospel of Matthew, rich patristic commentaries on the miracles of Jesus (4th century, various modern editions).

Gustavo Gutiérrez, Liberation Theology, a foundational work developing the social and political implications of the Gospel (Cerf, 1974).

Timothy Radcliffe, I call you friends, meditations of a Dominican on the Christian life incarnate in the contemporary world (Cerf, 2000).

Catechism of the Catholic Church, sections 2443-2449 on the love of the poor and the social doctrine of the Church.