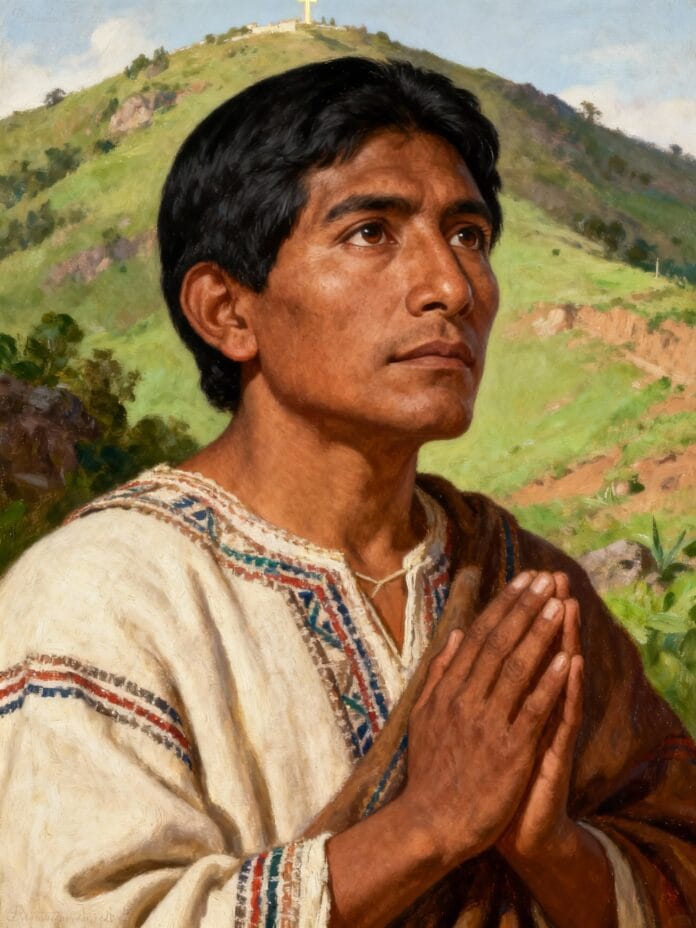

Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin (1474-1548), Chichimec Indian converted to Christianity, In Mexico City, he received four apparitions of the Virgin Mary. Married In December 1531, she asked him to build a sanctuary in Tepeyac. Faced with the bishop's skepticism, Juan Diego brought back miraculous roses in his cloak, imprinted with the image of Our Lady of Guadalupe. This humble peasant became the first indigenous saint of the Americas, canonized in 2002. His testimony reconciled the Catholic faith and Aztec culture, making Guadalupe the most visited Marian shrine in the world.

One morning in December 1531, an Indian peasant walked to Mass in the hills of Mexico City. The Virgin Married He appeared to her and revolutionized the religious history of the Americas. Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin became the messenger of reconciliation between two worlds: the Christian faith and the Aztec culture shattered by the Spanish conquest. His miraculous cloak, preserved intact for nearly five centuries, now attracts twenty million pilgrims a year. His memory reminds us that God chooses the humble to accomplish great works.

An Indian between two worlds

He was born in 1474 in Cuautlitlán, a village near present-day Mexico City. His family belonged to the Chichimec tribe, an indigenous people marginalized within the Aztec empire. The Aztecs then dominated central Mexico, with Tenochtitlan as their dazzling capital. Juan Diego grew up under their rule, witnessing their pyramidal temples and their bloody rituals. His name, Cuauhtlatoatzin, means "the talking eagle," evoking strength and wisdom in his culture.

In 1519, Hernán Cortés landed on the Mexican coast with five hundred Spanish soldiers. The conquest destroyed the Aztec empire in two years. Tenochtitlan fell in 1521 after a terrible siege. Temples were razed, idols smashed, and the nobility decimated. The Franciscans arrived in 1524 to evangelize this traumatized people. Juan Diego was fifty years old at the time and living in a shattered world.

He listened to Franciscan preaching with his wife, María Lucía. The Christian message resonated differently in his wounded heart. Where the conquistadors imposed by the sword, the friars offered a God of love. Juan Diego requested baptism in 1524. He received his new name, abandoned his old practices, and learned Christian prayers. His sincere conversion marked a radical break. Every Saturday, he walked fourteen kilometers to Tlatelolco for Mass and religious instruction.

His wife died in 1529. Juan Diego was left alone, living modestly from his farming. He lived with his uncle, Juan Bernardino, in Tolpetlac. Widowhood deepened his prayer life. Each trip to the church became an inner pilgrimage. He passed by the hill of Tepeyac, an ancient Aztec place of worship dedicated to the goddess Tonantzin. The Spanish had forbidden these pagan devotions. The hill remained deserted, silent, as if waiting.

On the morning of December 9, 1531, Juan Diego crossed Tepeyac to attend mass. Dawn barely illuminated the cacti and stones. Suddenly, a heavenly song stopped him in his tracks. A light flooded the hillside. He climbed and discovered a radiant young woman, dressed like an Aztec princess but speaking her Nahuatl language with gentleness. She introduced herself as the Mother of the true God, the giver of life. She asked for a temple to be built on that spot to demonstrate her love and mercy.

Juan Diego ran to inform Bishop Juan de Zumárraga, a strict Franciscan friar who had been in the village for three years. The bishop listened politely to the Indigenous peasant but didn't believe him. Too many stories were circulating, too many superstitions persisted. He prudently sent Juan Diego away. That same evening, Juan Diego returned to Tepeyac. The Lady reappeared, encouraged him, and asked him to come back to see the bishop the next day.

On December 10, the second episcopal visit took place. Zumárraga questioned Juan Diego at length about the details of the apparition. This time, he demanded tangible proof, that the Lady give a verifiable sign. Juan Diego agreed and promised to bring back this sign. Upon returning home, he found his uncle, Juan Bernardino, gravely ill. He remained at his bedside for the next two days. The fever worsened. On December 12, before dawn, Juan Bernardino requested a priest for the last rites.

Juan Diego hurried towards Tlatelolco. To save time, he bypassed Tepeyac to the east, hoping to avoid the Lady. He didn't want to disappoint her by arriving without the requested proof. But she intercepted him on this new route. Juan Diego explained the urgency, his uncle was dying. The Lady smiled tenderly. "Am I not here, I who am your Mother? Are you not under my protection?" She assured him that his uncle was already healed. She asked Juan Diego to climb to the summit of Tepeyac and pick the flowers that grew there.

Juan Diego climbs, perplexed. It's the middle of a Mexican winter, the hill is barren and rocky. Yet, at the summit, he discovers a garden of Castilian roses in full bloom. These Spanish roses don't grow in Mexico, much less in December. He cuts an armful. The Lady arranges them herself in her tilma, the agave-fiber cloak worn by peasants. She orders him not to open it until the bishop is present.

Juan Diego returns to the bishopric. The servants do it. to wait for Hours in the antechamber. Intrigued, they smelled the scent of roses. Finally admitted before Zumárraga and several witnesses, Juan Diego unfurled his tilma. Roses spilled onto the floor. But all eyes turned to the fabric: an image of the Virgin had miraculously imprinted itself upon it. Zumárraga fell to his knees. The image depicted a young mestizo woman, pregnant, surrounded by intertwined Aztec and Christian cosmic symbols.

The bishop had the image carried in a solemn procession to the cathedral. Juan Diego then guided it to Tolpetlac, where they found Juan Bernardino completely healed. The uncle confirmed that he had received a visit from the same Lady who had instantly cured him. She revealed her name to him: Guadalupe, a Spanish corruption of the Nahuatl Coatlaxopeuh ("she who crushes the serpent"). A first temporary chapel was built at Tepeyac. The image was installed there on December 26, 1531.

Juan Diego received episcopal permission to live as a hermit near the sanctuary. He spent seventeen years there in prayer, welcoming pilgrims, and maintaining the chapel. He tirelessly recounted his story to the thousands of visitors who flocked to the site. Conversions of Indigenous people increased dramatically. In ten years, nine million Indigenous people requested baptism. The cult of Guadalupe became the heart of the’evangelization Pacific Ocean of Mexico.

Juan Diego died on May 30, 1548, at the age of seventy-four. He was buried near the sanctuary he served. His tomb quickly became a place of veneration. Contemporary Nahuatl documents, notably the Nican Mopohua written in 1556 by Antonio Valeriano, preserve his direct testimony. These texts in the indigenous language lend historical credibility to the events.

The image that defies science

The tilma of Juan Diego still resides in the Basilica of Guadalupe in Mexico City. This agave fabric should have disintegrated long ago. Agave fibers typically last no more than twenty years. Yet, nearly five centuries later, the image remains intact without any protective varnish. This fact has intrigued scientists for decades.

In 1666, a clumsy cleaning spilled nitric acid on the upper right corner of the tilma. The fabric should have dissolved immediately. Instead, the acid left only a faint mark that gradually faded. Today, this stain has almost disappeared. The fabric seems to have self-repaired, an unexplained phenomenon. In 1791, a goldsmith was cleaning the gilded frame. He accidentally spilled etching solution on the tilma. No permanent damage occurred.

On November 14, 1921, an anarchist concealed a bomb in a bouquet of flowers placed at the foot of the image. The explosion destroyed the metal crucifix and shattered the surrounding stained-glass windows. The tilma, protected only by a thin pane of glass, remained intact. The faithful saw this as a direct, miraculous protection. These events fueled the legend of the image's invulnerability.

Tradition holds that the Virgin's eyes reflect the scene of December 12, 1531. In 1929, a photographer discovered a silhouette in the right iris. In 1951, an artist confirmed seeing a bearded man reflected in both eyes. In the 1980s, ophthalmologists analyzed the eyes using computer magnification techniques. They claimed to distinguish up to thirteen figures: Juan Diego opening his tilma, the kneeling bishop, and Spanish and Indigenous witnesses.

This discovery is captivating. How could a 16th-century artist have painted microscopic reflections invisible to the naked eye? Skeptics reply that the collective imagination projects shapes onto irregularities in the fabric. The debate between science and faith flares up regularly. Official studies commissioned by the Church remain cautious. They note anomalies without determining their miraculous origin.

In 1936, Nobel laureate chemist Richard Kuhn analyzed two fibers of the tilma. He concluded that the pigments were of no known origin: neither plant, nor mineral, nor animal. His report remains contested. Subsequent analyses have identified conventional pigments. The scientific controversy persists. Some researchers claim that the image has no preparatory sketches, no visible brushstrokes. Others detect later retouching of certain parts, such as the golden rays and the moon.

Biophysicist Philip Callahan studied the image in 1979 using infrared techniques. His report distinguished between the original, unexplained image and the later, conventionally painted additions. He noted that the original image showed no brushstroke direction and appeared to be embedded in the fibers rather than deposited on the surface. His findings, published in specialized journals, revived the miraculous hypothesis.

The symbolism of the image fascinates theologians. The Virgin wears a black sash characteristic of pregnant Aztec women. She is depicted before the sun, on the moon, carried by an angel. These symbols represent the Apocalypse 12: «A great sign appeared in heaven: a woman clothed with the sun, with the moon under her feet.» The Aztecs worshipped the sun and moon as major deities. The image shows the Virgin Mary dominating these celestial bodies, affirming the supremacy of the Christian God.

The forty-six stars visible on the blue mantle correspond exactly to the position of the constellations in the sky over Mexico City on December 12, 1531, the winter solstice. This astronomical accuracy is astounding. It suggests a level of scientific knowledge impossible for a 16th-century Indian painter. Skeptics object that this correspondence remains approximate and that later additions altered the original drawing.

The four-petaled flower repeated on the pink dress is the nahui ollin, the Aztec symbol of the center of the universe and cosmic movement. The Aztecs believed they were living in the fifth age of the world. This flower signifies that the Virgin Mary brings a new spiritual center. She does not destroy Indigenous culture but rather fulfills and purifies it. This symbolic inculturation explains the mass conversion of Indigenous people.

The Virgin's face displays mixed features, neither purely European nor purely Aztec. This visual synthesis reconciles the two warring peoples. The conquistadors and missionaries see in her the Mother of God. The Indigenous people recognize a compassionate mother who speaks their language and respects their symbols. Guadalupe becomes the bridge between two antagonistic worlds. She inaugurates a unique Mexican identity, founded on cultural and religious fusion.

Pilgrimages to Tepeyac began to flourish in 1531. Successive chapels replaced the first hermitage. In 1695, an imposing colonial basilica was consecrated, welcoming millions of visitors annually. In the 20th century, the influx of pilgrims necessitated a new, modern basilica, inaugurated in 1976. The old sanctuary was in danger of collapsing due to ground subsidence. The image was transferred to the contemporary building, where it is enthroned above the altar, visible from all angles.

Successive popes have honored Our Lady of Guadalupe. Benedict XIV proclaimed her patron saint of New Spain in 1754. Pius X declared her patron saint of Latin America in 1910. Pius XII patron saint of the Americas in 1945. John Paul II visited the shrine five times. He beatified Juan Diego there in 1990, and then canonized him in 2002 during a Mass attended by twelve million faithful. François visited in 2016, highlighting the importance of Guadalupe for the’Universal Church.

When God chooses the humble

Juan Diego embodies the paradox of the Gospel: God entrusts his plans to the humblest. This widowed peasant, uneducated and newly converted, becomes the instrument of a spiritual revolution. He has no social authority, no eloquence, no influence. Yet, the Virgin prefers him to bishops, theologians, and the powerful. She thus echoes the logic of the Magnificat: "He has brought down the powerful from their thrones and lifted up the humble."«

The first spiritual lesson concerns trusting obedience. Juan Diego doubts his mission. When the bishop sends him away, he could give up. When the Lady sends him to the summit to find impossible roses, he could protest. He simply obeys, without calculation. This docility is not passivity but active faith. He acts despite incomprehension, apparent failure, the absurdity of the request. His quiet perseverance moves mountains of skepticism.

The second lesson concerns availability at the crucial moment. Juan Diego happened to be passing through Tepeyac on December 9th. He wasn't looking for anything in particular. God intervened in the ordinariness of a daily commute. Great vocations are rarely born in the extraordinary, but in loyalty to the little things. Juan Diego walked towards Mass, fulfilling his modest religious duty. This regularity prepares him to receive the exceptional.

The third lesson teaches the priority of family ties. On December 12, Juan Diego avoids the Lady because his uncle is dying. He puts his loved one's service before his supernatural mission. The Virgin approves of this hierarchy. She doesn't reproach him, doesn't delay his uncle. She heals Juan Bernardino instantly and sends Juan Diego to accomplish both tasks. Love of God and neighbor are never truly opposed. service to the poor and illness take precedence over spectacular appearances.

The fourth lesson reveals the importance of cultural embodiment. The Virgin appears as a young Aztec woman, speaks Nahuatl, uses their cosmic symbols, and calls herself "She Who Crushes the Serpent"—a reference to the Aztec founding myth as much as to Genesis 3,15. It does not ask the Indians to renounce their culture but to purify it and fulfill it in Christ. This divine pedagogy respects the identity of peoples while raising them towards the universal.

Today's Gospel resonates deeply: "I praise you, Father, because you have hidden these things from the wise and learned, and revealed them to little children." Juan Diego perfectly illustrates this verse. Spanish theologians are debating methods of«evangelization complex. God chose an illiterate Indian to accomplish in ten years what missions could not have achieved in centuries. Divine wisdom scoffs at our human strategies. It prefers a humble heart to a thousand degrees.

This divine preference challenges our age, obsessed as it is with skills and performance. We value expertise, visibility, and measurable efficiency. Juan Diego reminds us that God first seeks the docility of the heart. He can accomplish more with a humble, willing person than with a proud genius. This truth disturbs our modern meritocracy but liberates those who believe themselves useless.

The message of Guadalupe transcends Mexican Catholicism. It speaks to all the colonized, dominated, and despised of history. The Virgin does not address the Spanish conquistadors but the vanquished Aztecs. She comes to console those whom history has crushed. She affirms their dignity when the world reduces them to slavery. She adopts their language, their features, their symbols. This preferential choice for the poor anticipates liberation theology by five centuries.

For contemporary Catholics, Juan Diego proposes a model of holiness Accessible. No spectacular martyrdom, no thaumaturgical miracles, no doctorate in theology. Just a peasant who prays regularly, serves humbly, and simply obeys. He lives his faith in the ordinary, walks to Mass every Saturday, cares for his sick uncle, and welcomes visitors for seventeen years. This holiness everyday life is within everyone's reach.

To you, Mother of the humble

Virgin Married, You chose Juan Diego from among the little ones of this world to reveal your maternal tenderness. You didn't look at his poverty, his lack of education, his despised origins. You saw his open and docile heart. Teach us to recognize that God prefers the’humility to human glory, simplicity to learned eloquence, loyalty hidden from spectacular works.

Mother of Guadalupe, you drew close to peoples wounded by history. You spoke the language of the vanquished, bore their symbols, and shared their features. You restored their dignity when the world crushed them. Grant us that same compassionate gaze for all those whom our society marginalizes. migrants, The poor, the excluded, the forgotten. May we, like you, know how to draw near to them without condescension or paternalism.

Our Lady, who crushed the serpent, you fulfilled the promise made to Eve in the Garden of Eden. You are the new Eve, the one who atoned for the first act of disobedience through her total "yes" to God. Help us to fight the evil that creeps into our lives: the pride that imprisons us, the selfishness that isolates us, the fear that paralyzes us. Strengthen our will to choose good daily, humbly, and perseveringly.

You who bear Christ in your womb in the miraculous image, you remind us that every baptized person carries Jesus within them. We are the living temple of the Trinity. Awaken in us this awareness of being bearers of God. May this extraordinary dignity transform our view of ourselves and others. May we treat each person as the sacred sanctuary they are, regardless of their social standing.

Mother who healed Juan Bernardino from afar, you show us that nothing is impossible for God. Our sick, our suffering, our human dead ends never discourage you. Intercede for all those who are dying today without consolation, who despair without hope, who suffer without relief. Remind everyone of your words to Juan Diego: «Am I not here, I who am your Mother? Are you not under my protection?»

Lady of the indestructible tilma, your image traverses the centuries uncorrupted. It testifies that God's work withstands time and destruction. Protect the Church, strengthen vocations, and revive discouraged communities. May your maternal presence sustain all those who serve faithfully in obscurity, without recognition or visible results. Their hidden faithfulness bears eternal fruit.

Queen of the Americas, you reconciled warring peoples through your peacemaking presence. Even today, so many divisions tear apart our families, our churches, our nations. Be the architect of reconciliation between those whom history, politics, or religion have set against each other. Teach us to build bridges rather than walls, to seek what unites rather than what divides.

Mother, who asks for a sanctuary at Tepeyac, you desire a place to pour out your graces upon all who call upon you. Make our hearts living sanctuaries where you dwell permanently. May our daily lives become this temple where you distribute mercy, consolation, strength, and hope. May each of our acts of love be another stone in the spiritual edifice you are building.

Grant us the grace of Juan Diego: that quiet perseverance in the mission received, that unwavering confidence despite the obstacles, that humility who seeks neither glory nor recognition. May we serve to the end with the same faithfulness he showed for seventeen years near your image. Amen.

To live

- Read Luke 1,46-55, the Magnificat of Married, and note down a phrase that resonates personally today as a call to action.’humility or to trust.

- Identify a marginalized person in your circle and take a concrete step of recognition: greet warmly, really listen, offer a simple service.

- Pray for ten minutes before a Marian image, confiding a situation where you feel small, powerless, or misunderstood, while whispering the words of Married To Juan Diego: "Am I not here, I who am your Mother?"«

Tepeyac, hill of all graces

The Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe stands at the foot of Tepeyac Hill in Mexico City's northern district. The religious complex comprises the old colonial basilica, built in 1695 and now closed for worship due to subsidence, and the newer, modern basilica, built in 1976 and designed by architect Pedro Ramírez Vázquez. The latter can accommodate ten thousand worshippers at a time. Its circular plan allows all pilgrims to see the miraculous image displayed behind the main altar under a glass canopy.

The tilma of Juan Diego is 1.70 meters high. It is made of two pieces of agave fabric sewn vertically. The image itself measures 1.43 meters by 1.05 meters. A moving walkway passes in front of the image to manage the constant flow of visitors who come to view it. Twenty million pilgrims visit the shrine each year, making Guadalupe the second most visited Catholic pilgrimage site in the world after the Vatican.

Tepeyac Hill overlooks the sanctuary. A monumental Stations of the Cross ascends its slopes. At the summit, a modern chapel marks the exact spot of the apparitions. Pilgrims often climb on their knees in devotion. The view encompasses the vastness of Mexico City, a megalopolis of twenty-two million inhabitants. This striking contrast between the original rural site and the rampant urbanization serves as a reminder that faith transcends historical transformations.

Several secondary shrines dot the esplanade. The Chapel of the Pocito (Little Well) houses a spring reputed to have miraculous properties since the 17th century. The faithful come there to collect holy water. The Chapel of the Indians, built in 1649, was the first permanent place of worship after the original hermitage. It preserves remarkable Mexican Baroque elements. The Basilica Museum displays six hundred years of Mexican religious art and votive offerings given in gratitude for blessings received.

The relics of Juan Diego rest beneath the altar of the old basilica, although their exact location has been debated. The house where he lived with his uncle in Tolpetlac has been converted into a chapel. The site of Juan Bernardino's miraculous healing is also marked. These secondary sites allow us to geographically reconstruct the events of December 1531.

The Feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe, on December 12, draws immense crowds. Millions of pilgrims converge on Tepeyac during the preceding week. Many walk for several days from distant provinces. Groups of traditional dancers in Aztec costumes honor the Virgin in front of the basilica. Mariachis play Marian hymns all night long. The atmosphere blends religious fervor with popular Mexican celebration.

There canonization by Juan Diego in 2002 strengthened the devotion. John Paul II celebrated Mass before twelve million faithful in Azteca Park. He emphasized that Juan Diego "facilitated the fruitful encounter of two worlds" and "contributed powerfully to the«evangelization »This official recognition validated the veneration centuries-old Mexican loyalty to their compatriot.

Guadalupe iconography is ubiquitous in Mexico. The image adorns taxis, restaurants, and the walls of homes. It appears on medals, scapulars, and tattoos. This popularity testifies to a profound appropriation of the symbol. Guadalupe embodies Mexican identity as much as the Catholic faith. She transcends social classes and political orientations. Atheists and believers alike recognize her as part of the national heritage.

The apparitions of Our Lady of Guadalupe have inspired countless works of art. Colonial painters produced numerous copies of the original image. Miguel Cabrera (1695-1768), the greatest Mexican Baroque painter, created several famous versions. In the 20th century, Diego Rivera, despite being an atheist, depicted Juan Diego in his murals as a symbol of indigenous resistance. Frida Kahlo reinterpreted Guadalupe iconography in several paintings.

The devotion spread throughout Latin America. Local shrines dedicated to Guadalupe exist in Argentina, Colombia, Puerto Rico, and Peru. In the United States, the Hispanic community has built dozens of Guadalupe parishes and chapels. The cult accompanies Mexican migrations and maintains the cultural identity of expatriates. The celebrations on December 12th bring together Hispanic communities from Los Angeles to New York.

Liturgy

Bible readings: Zechariah 2:14-17 speaks of God's presence dwelling in Jerusalem. Luke 1,26-38 recounts the Annunciation to Married. These texts parallel the appearance of Juan Diego as a new annunciation for the Americas.

Responsorial Psalm: Judith 13 celebrates the woman blessed above all others, a direct echo of the angelic salutation used for Married and invoked before the image of Guadalupe.

Preface (proper): Famous Married Mother of the Americas, new Eve, Star of the’evangelization, who chose Juan Diego as a messenger of reconciliation.

Prayer: Request to follow the example of docility and’humility by Juan Diego to welcome God's calls in the ordinariness of daily life.

Suggested song: «"La Guadalupana", a traditional Mexican Mariological hymn, or "Magnificat" in its Latin or vernacular versions, emphasizing the divine choice of the humble.

Liturgical color: White, proper to Marian feasts, symbolizing the joy and purity of the Mother of God appearing to the little ones of her people.