Reading from the Book of Genesis

When he created the heavens and the earth,

God said again:

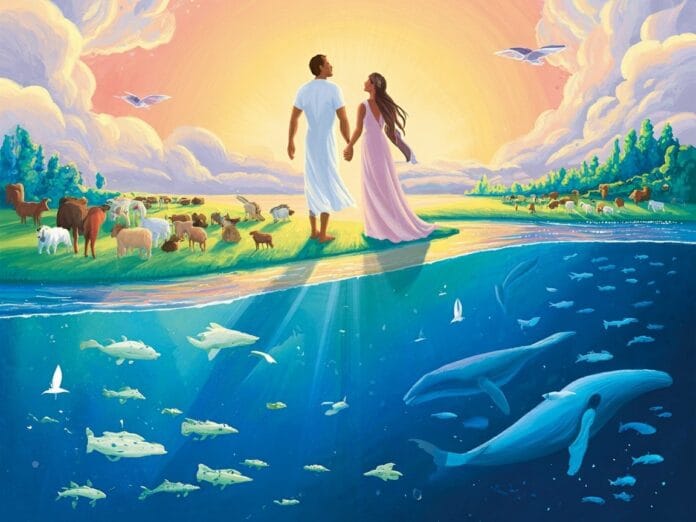

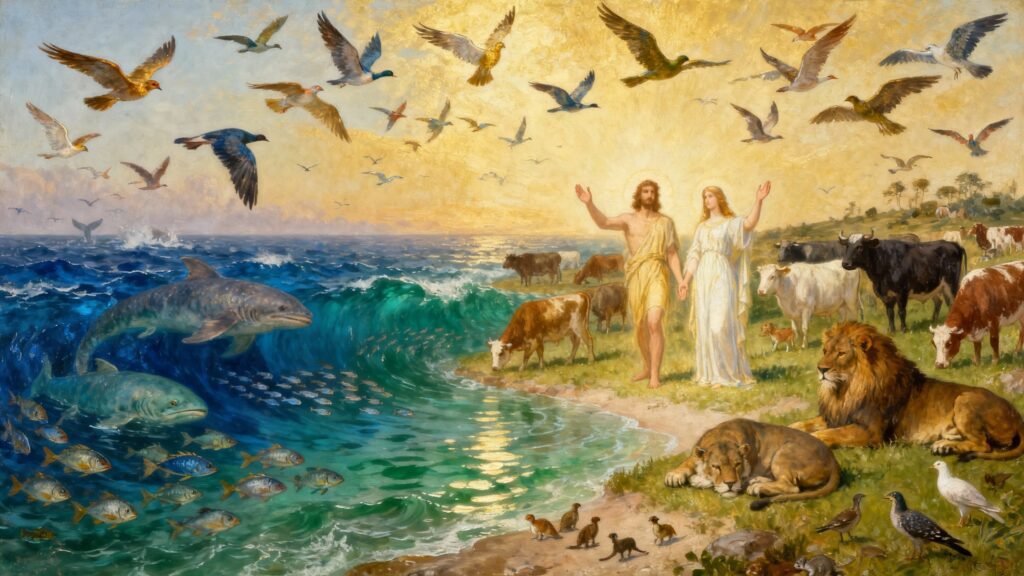

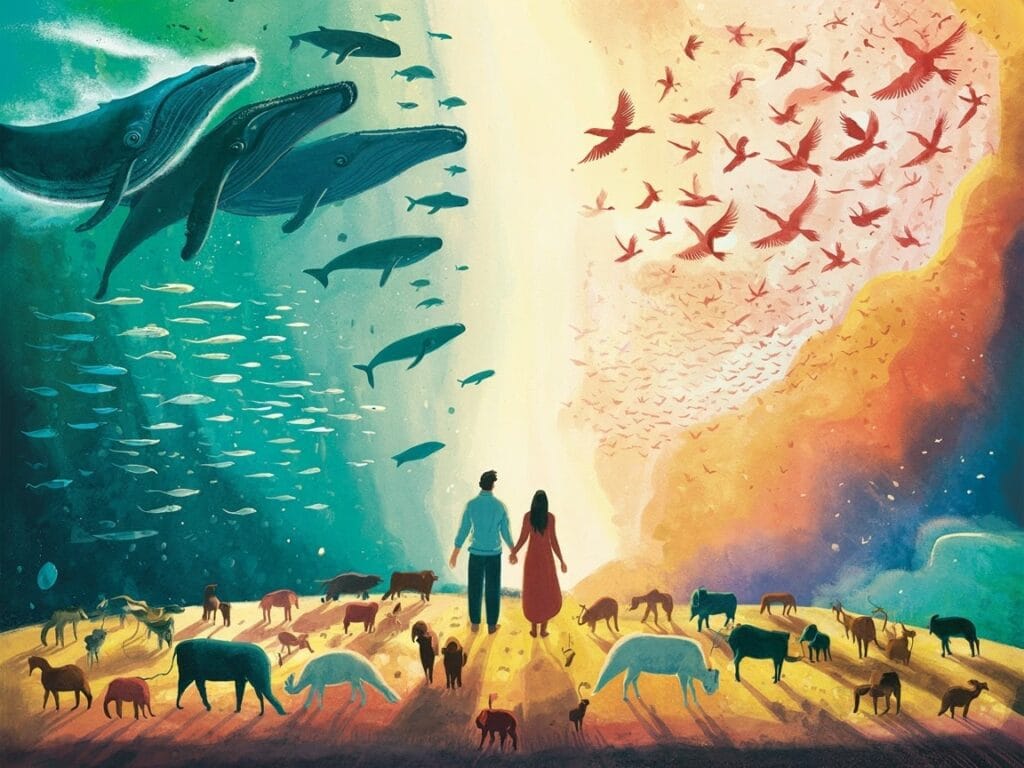

"Let the waters abound

of a profusion of living beings,

and birds fly above the earth,

under the firmament of the sky.

God created them according to their kind,

the great sea monsters,

all living beings that come and go

and abound in the waters,

and also, according to their kind,

all the birds that fly.

And God saw that it was good.

God blessed them with these words:

“Be fruitful and multiply,

fill the seas,

let birds multiply on the earth.

There was evening, there was morning:

fifth day.

And God said:

“Let the earth bring forth living beings

according to their kind,

cattle, creatures and wild beasts

according to their kind.

And so it was.

God made the wild beasts according to their kinds,

livestock according to their kind,

and every creeping thing of the earth according to its kind.

And God saw that it was good.

God says:

“Let us make man in our image,

according to our likeness.

May he have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the air,

of cattle, of all wild beasts,

and all the critters

who come and go on earth."

God created man in his own image,

in the image of God he created him,

He created them male and female.

God blessed them and said to them:

“Be fruitful and multiply,

fill the earth and subdue it.

Be the masters

fish of the sea, birds of the air,

and all the animals that come and go on the earth."

God said again:

“I give you every plant that bears its seed

over the whole surface of the earth,

and every tree whose fruit bears its seed:

such shall be your food.

To all the animals of the earth,

to all the birds of the air,

to everything that comes and goes on earth

and who has the breath of life,

I give every green herb as food.

And so it was.

And God saw everything that he had made;

and behold: it was very good.

There was evening, there was morning:

sixth day.

Thus heaven and earth were finished,

and all their deployment.

On the seventh day,

God had completed the work he had done.

He rested on the seventh day,

of all the work he had done.

And God blessed the seventh day:

he sanctified it

since, on that day, he rested

of all the work of creation that he had done.

Such was the origin of heaven and earth

when they were created.

– Word of the Lord.

Created in the Image of God: The Revolutionary Dignity of Humanity

Discover how the Creation story transforms our vision of ourselves and our vocation in the world.

The first chapter of Genesis doesn't simply tell a cosmic creation story: it reveals a shattering truth about human identity. By proclaiming that man and woman are created "in the image of God," this foundational text establishes a universal dignity that transcends all boundaries. For believers today, faced with ecological, social, and existential challenges, this account offers an unshakeable foundation: each person carries within them a divine imprint that calls them to responsibility, creativity, and connection.

This article explores the revolutionary significance of the Creation story in Genesis 1. We will first situate this text in its literary and theological context, before analyzing the profound meaning of the expression "image of God." We will then unfold three major themes: the ontological dignity of every human being, the creative and relational vocation, and ecological responsibility. Finally, we will listen to the echoes of this message in the Christian tradition and propose concrete ways to live this truth in our daily lives.

Context

The creation story that opens the book of Genesis belongs to the priestly tradition, probably written during or after the Babylonian exile, in the 6th century BC. This context is crucial: Israel, deported to Babylon, found itself confronted with Mesopotamian mythologies glorifying capricious and violent gods. Faced with these cosmogonic narratives marked by chaos and divine struggles, the biblical authors proposed a radically different vision: a unique God who creates through his word, with order, goodness, and intention.

The structure of the text is masterful. The narrative is organized into six days, followed by a seventh day of rest, thus establishing the Sabbath rhythm at the heart of creation itself. Each day follows a repetitive pattern: God speaks, God does, God sees that it is good. This chanted litany creates cosmic music, a celebration of the order and beauty of the world. The fifth day sees the appearance of aquatic and winged creatures, blessed by God and invited to fertility. The sixth day marks the climax: land animals, then humanity.

The phrase "Let us make man in our image, according to our likeness" introduces a break in the narrative. Until now, God created by simple declaration. Here, he deliberates, as if the creation of humanity required special consideration. The plural "Let us make" has given rise to countless interpretations: some see it as a plural of majesty, others as a deliberation within the heavenly court, still others as a prefiguration of the Trinity. But the essential point lies elsewhere: humanity occupies a unique place in creation.

The text then specifies that God creates man "in his image," then immediately adds, "male and female he created them." This sexual duality is constitutive of the divine image, which is revolutionary in the ancient context where only kings claimed to embody the image of the gods. Here, every human being, man or woman, bears this dignity. Divine blessing accompanies this creation: "Be fruitful and multiply, fill the earth and subdue it." This mission of domination has been terribly misunderstood over the centuries, sometimes justifying the savage exploitation of nature. Yet, the verb "subdue" must be reread in light of the entire text: God entrusts the earth to humanity as a gardener entrusts his garden, with the expectation of responsible care.

The initial diet is vegetarian, for both humans and animals. This original harmony suggests that violence and predation are not part of God's initial plan. Finally, God contemplates the whole of his work and pronounces a definitive judgment: "Behold, it was very good." No longer simply "good," but "very good." Creation reaches its fullness with humanity. On the seventh day, God rests, thus sanctifying the Sabbath and inscribing rest at the heart of the creational order. This divine rest is not fatigue, but satisfied contemplation, an invitation to savor the goodness of what exists.

Analysis: The image of God, an ontological dignity

The phrase "image of God" is one of the most powerful and most debated in the entire biblical tradition. What does it mean to be created in the image of God? This question has spanned centuries and cultures, generating an inexhaustible wealth of theological, philosophical, and spiritual reflections.

Let us first clarify what this expression does not mean. It does not refer to a physical resemblance, because the Bible insists on the transcendence of God, who cannot be represented by any graven image. Nor does it designate a particular capacity, such as reason or moral conscience, that would distinguish humans from animals, even if these dimensions are included in the notion. The image of God is more fundamental: it designates a relational and ontological status.

In the ancient Near East, statues of the gods in temples were considered divine images, allowing the deities to be present and active in the world. Likewise, kings presented themselves as living images of the gods on earth, their authorized representatives. The text of Genesis radically democratizes this notion: every human being, regardless of social status, gender, or abilities, is the image of God. This affirmation is truly revolutionary. It establishes a fundamental equality between all members of the human species and confers on each one an inalienable dignity.

Being the image of God means first and foremost being God's representative on earth. Humanity is given a mission: to manage creation, cultivate it, and care for it in the name of God. This vocation entails immense responsibility but also joyful creativity. Just as God creates and orders, human beings are called to extend this creative work, not out of pride, but by participating in divine action. Every act of human creation—artistic, technical, social—can be understood as an echo of this primary vocation.

Being the image of God then means being capable of relationship. God says, "Let us make," and creates humanity as "male and female." Relationship, otherness, and dialogue are inscribed in the heart of the human being. We are not isolated monads, but beings-in-relation. This relational dimension reflects something of God himself, who, even in the Old Testament, reveals himself in dialogue with his creation. The Fathers of the Church will develop this intuition by contemplating the Trinity: God himself is communion, a relationship of love between Father, Son, and Spirit. Humanity, created in his image, is therefore fundamentally called to communion.

Being the image of God finally implies an orientation toward the transcendent. Unlike animals who live in the immediacy of the present, human beings can turn toward eternity, question meaning, and seek God. This spiritual quest is not a superfluous luxury, but the very expression of our image-like nature. We are made for God, and our heart remains restless until it rests in Him, Saint Augustine wrote.

The magnificent paradox of this doctrine is that it is the foundation of both human humility and greatness. Humility: we are not God, we are only his image, fragile, limited, sometimes disfigured by sin. Greatness: this image elevates us above all creation, gives us infinite value, and prohibits any instrumentalization or reduction of the human person.

The universal and inalienable dignity of every person

If every human being is created in the image of God, then human dignity is not a social conquest, a privilege granted by law, or a status that can be lost. It is an ontological given, inscribed in the creative act itself. This truth, proclaimed at the very beginning of the Bible, has staggering implications for our understanding of justice, ethics, and social relations.

First, this dignity is universal. It knows no distinction of race, sex, age, intellectual or physical ability, social or economic status. The text insists: "male and female he created them." Fundamental equality between the sexes has been affirmed from the beginning, even if biblical and human history will show how much this equality has been flouted. But the principle remains, unshakeable, the foundation of every struggle for equality and human rights. Every emancipation movement, whether the abolition of slavery, the fight for civil rights, or the recognition of the equality of men and women, finds its profound theological legitimacy here.

Second, this dignity is inalienable. We cannot lose it, whatever our actions. Even the most hardened criminal, even the person in the deepest coma, even the microscopic embryo retains this divine imprint. This does not mean that all actions are equal or that justice has no place. But it does prohibit reducing a person to their actions, dehumanizing them, or stripping them of their intrinsic value. This conviction is the basis of Christian opposition to the death penalty, defense of the most vulnerable, and respect for all human life from conception to natural death.

Third, this dignity calls for radical respect for others. To see the face of another is to contemplate a living icon of God. An offense against a human being becomes, in a sense, an offense against God himself. This perspective transforms our daily relationships: the stranger encountered on the street, the annoying colleague, the ignored beggar, the forgotten prisoner—all carry within them this divine light that demands recognition and respect. The constant temptation to rank human beings according to criteria of performance, usefulness, or social conformity runs up against the insurmountable wall of this theological truth.

Christian history, we must humbly admit, has not always honored this truth. Slavery was practiced and even justified by Christians. Women were relegated to subordinate positions. Colonized peoples were treated as inferior. But each time, prophetic voices arose to recall the founding principle: all, absolutely all, are created in the image of God. These voices drew their strength from this Genesis account, demonstrating that the Word of God possesses a permanent critical force against all forms of oppression and dehumanization.

Today, this truth remains entirely relevant. In the face of new forms of exclusion—discrimination against migrants, contempt for the poor, soft eugenics through prenatal diagnosis, the transhumanist temptation to “perfect” humanity—the story of Genesis reminds us that human value is measured neither by performance nor conformity, but is received as a free gift from God. This perspective establishes an ethic of welcome, care, and attention to the most vulnerable. It inspires a policy of solidarity rather than competition, an economy of sharing rather than accumulation.

Concretely, recognizing the image dignity of every human being should transform our daily attitudes. This means rejecting hasty judgments and the backbiting that reduces others to caricatures. It involves seeking the good in everyone, even in those who have hurt us. It requires defending the rights of those who have no voice, opposing all forms of discrimination. This demand may seem overwhelming, but it flows naturally from our faith in a God who has seen fit to confer on every human person the extraordinary title of divine image.

Creative and relational vocation of humanity

The creation of humanity in God's image is not limited to a passive status. It implies an active vocation: to extend God's creative work and to live in relationship. These two dimensions—creativity and relationality—are intimately linked and define the human mission in the world.

God creates through his word: he speaks, and things happen. This creative power is expressed in the order, beauty, and diversity of creation. Human beings, in his image, are also called to create. Not from nothing—only God creates ex nihilo—but from what is given to him. This human creativity is manifest in all areas: art and culture, science and technology, social and political organization, work and the economy. Each time human beings transform matter, order chaos, or bring beauty or utility into being, they extend, in their own way, the divine creative act.

This vision gives human work a spiritual dignity. Far from being a curse or a mere economic necessity, work becomes participation in God's work. The peasant who cultivates the land, the craftsman who shapes matter, the teacher who awakens consciences, the scientist who unravels the mysteries of the universe—all fulfill, each in their own way, this creative vocation. Even the most humble tasks, when carried out with care and attention, reflect this collaboration in the divine work. Saint Paul would later write that we are "co-workers with God" (1 Cor 3:9), thus giving explicit formulation to what was already implicit in the Genesis account.

But beware: this creative vocation is not a carte blanche for exploitation. The command to "subdue" the earth and "dominate" animals must be reread in light of the entire divine plan. It is a domination of service, not arbitrary or violent domination. God entrusts creation to humanity like a precious garden to be cultivated and guarded. Technical mastery does not exempt us from moral responsibility. On the contrary, the more our capacity to intervene in nature increases, the greater our responsibility. The current ecological crisis is a painful reminder that we have betrayed this vocation by exploiting the earth as an infinite resource to be plundered rather than a sacred gift to be preserved.

The relational dimension of the divine image is just as fundamental. “He created them male and female”: sexual duality is not a biological detail, but an essential structure of human existence. We are beings-for-relationship, turned toward the other, incomplete in solitude. The parallel narrative in chapter 2 of Genesis will develop this intuition: “It is not good for the man to be alone” (Gen 2:18). Sexual otherness is the primary, but not exclusive, form of this relational openness. It extends into all forms of human communion: friendship, family, community, society.

This relational vocation finds its ultimate foundation in the very nature of God. If God is love, as Saint John affirms (1 Jn 4:8), then the human being created in his image is made to love. Love is not an optional sentiment or a moral luxury, but the fundamental law of our existence. We are fulfilled in the gift of ourselves, in the recognition of others, in the building of authentic bonds. Conversely, isolation, selfishness, and the instrumentalization of others disfigure us and distance us from our deepest truth.

Concretely, living this creative and relational vocation requires integrating several dimensions into our daily lives. First, viewing our work, whatever it may be, as a participation in God's work, seeking to accomplish it with excellence and conscientiousness. Second, cultivating our creative talents—artistic, intellectual, manual—not out of pride, but as a response to the divine call inscribed within us. Third, investing in relationships: devoting time and energy to our loved ones, cultivating friendships, and engaging in communities where we can give and receive. Fourth, resisting the temptation of self-sufficient solitude or the exploitation of others, two symmetrical temptations that negate our relational vocation.

Ecological responsibility and guardianship of creation

The Genesis account places humanity at the apex of creation, entrusting it with a mission of dominion over animals and subjugation of the earth. This statement has historically been interpreted, especially in the modern Western world, as a license to unlimited exploitation of natural resources. This reading has contributed to the ecological catastrophe we are experiencing today. Yet a careful rereading of the text reveals a completely different perspective: that of ecological responsibility at the heart of human vocation.

Let's review the vocabulary used. The Hebrew verb "radah," translated as "to dominate," does indeed designate the exercise of authority. But in the biblical context, this authority is always understood as a responsibility of service. The ideal king, in the Bible, is not a capricious tyrant but a shepherd who cares for his flock, a judge who defends the weak. Likewise, human dominion over creation must be exercised according to the model of God himself, who creates with kindness, order, and care. Humanity is called to be the faithful steward of creation, not its absolute owner.

The narrative emphasizes the goodness of creation. At each stage, God contemplates his work and declares, "This was good." After the creation of humanity, the judgment becomes, "This was very good." This intrinsic goodness of creation precedes any usefulness for human beings. Creatures have value in themselves, because they are willed and loved by God. This perspective establishes a theological ecology that recognizes the inherent dignity of nature, independent of its human use. Oceans, forests, animals are not mere resources to be exploited, but creatures bearing the seal of their Creator.

The initial vegetarian diet, for both humans and animals, suggests an original harmony free from violence. Of course, this idyllic regime will be quickly modified after the Flood (Gen 9:3), thus recognizing the realism of a world marked by sin. But the ideal remains as an eschatological horizon: the prophet Isaiah will evoke a time when "the wolf will dwell with the lamb" (Is 11:6), thus regaining the lost harmony of the Garden of Eden. This vision reminds us that predation and exploitation are not the last word in history.

Ecological responsibility also stems from the commandment to cultivate and keep the garden (Gen 2:15). These two verbs—to cultivate and to keep—admirably define the right relationship with nature. To cultivate is to transform, improve, and make fruitful. Human beings are not called to leave nature completely wild, but to cooperate with it to derive sustenance and beauty from it. To keep is to protect, preserve, and transmit. The earth does not belong to us as absolute property; we receive it as an inheritance and must transmit it to future generations. This dual requirement—creative transformation and responsible preservation—defines an integral ecology that rejects both paralyzing conservationism and destructive productivism.

Pope Francis, in his encyclical Laudato si', masterfully developed this ecological theology rooted in Genesis. He denounces the "throwaway culture" and the "technocratic paradigm" that reduce nature to a set of exploitable resources. He calls for an "integral ecology" that recognizes the interconnectedness between environmental and social crises. The poorest are the first victims of ecological degradation: they suffer pollution, climate disasters, and the scarcity of resources. Ecological responsibility is therefore inseparable from social justice.

Concretely, living this responsibility involves conversions on several levels. On a personal level: adopting a sober lifestyle, reducing our consumption, favoring environmentally friendly products, limiting our waste. On a community level: supporting local ecological initiatives, participating in conservation or restoration projects, raising awareness among those around us. On a political level: campaigning for ambitious environmental policies, supporting environmental organizations, voting for committed representatives. On a spiritual level: cultivating an admiring contemplation of nature, recognizing in it the work of God, developing gratitude for the gift of creation.

This ecological responsibility is not a gloomy burden, but a joyful participation in God's creative work. By caring for the earth, we honor its Creator. By protecting biodiversity, we preserve the richness of God's handiwork. By passing on a habitable planet to future generations, we fulfill our calling as faithful stewards.

Tradition and liturgy

The theme of the image of God has pervaded the entire Christian tradition, provoking uninterrupted theological reflection and nourishing the spirituality of believers. The Fathers of the Church, in particular, meditated deeply on this notion, enriching it with new perspectives in the light of the mystery of Christ.

In the 2nd century, Irenaeus of Lyons distinguished between "image" and "likeness." According to him, the image (eikôn) refers to the natural capacities of human beings—reason, freedom, the capacity for relationship—which are never completely lost. Likeness (homoiosis), on the other hand, refers to holiness, conformity to God, which can be lost through sin but restored by grace. This distinction would profoundly influence both Eastern and Western theology.

The Greek Fathers, notably Gregory of Nyssa and Maximus the Confessor, developed a theology of divinization (theosis). Human beings, created in the image of God, are called to become participants in the divine nature (2 Pet 1:4). This participation does not abolish the difference between Creator and creature, but elevates humanity to an intimate communion with God. The spiritual life thus becomes a path of progressive restoration of the image disfigured by sin and of growth in the divine likeness.

Augustine of Hippo explores another dimension: he searches in the human soul for traces of the Trinity. Memory, intelligence, and will, he argues, reflect the Trinitarian structure of God. This psychological analogy will become classic in Western theology, even though it has been criticized for excessively intellectualizing the divine image.

In the 13th century, Thomas Aquinas systematized patristic reflection. He asserted that the image of God resides primarily in the intellect and the will, spiritual faculties through which human beings can know and love God. But he also insisted that this image finds its perfection in Christ, the perfect Image of the Father (Col 1:15). All Christology is therefore also an anthropology: to know Christ is to know what humanity is called to become.

The Protestant Reformation emphasized the disfigurement of the divine image by sin. Luther and Calvin emphasized the radical corruption of human nature after the Fall, while maintaining that the image remains in some way, even if obscured. Only the grace of Christ can restore this image and allow human beings to rediscover their original vocation.

The Second Vatican Council would take up this theme in the constitution Gaudium et Spes, affirming that Christ "fully manifests man to himself" (GS 22). It is by contemplating the incarnate Word that we understand our own dignity and vocation. The mystery of the Incarnation reveals that God wanted to unite himself with humanity in the most intimate way possible, assuming our nature to elevate us to divine participation.

Liturgically, the theme of the image of God resonates particularly in baptismal and Easter celebrations. Baptism is understood as the restoration of the image disfigured by original sin. The catechumen, immersed in the baptismal waters, dies to sin and is resurrected as a new man, in the image of Christ. Easter celebrates this recreation of humanity: Christ, the new Adam, inaugurates a new creation where the divine image shines forth in all its glory.

The Eucharistic prayers also echo this theme. The offertory presents the bread and wine as "fruit of the earth and of human labor," thus recognizing the collaboration between divine creation and human creativity. The epiclesis invokes the Holy Spirit to transform these gifts, but also to transform the assembly into the Body of Christ, the ultimate fulfillment of humanity's image-based vocation.

Meditations

To concretely integrate the message of Genesis into our daily lives and our prayers, here is a spiritual journey in seven stages, inspired by the seven days of creation.

Day One: Contemplation of Personal DignityTake a moment of silence to meditate on your own dignity as God's image. Repeat to yourself, "I am created in the image of God." Let this truth sink into your consciousness, dispelling thoughts of self-deprecation or negative comparison. Accept yourself as you are, with your strengths and weaknesses, as a creature willed and loved by God.

Second day: Recognition of the dignity of others. Choose someone close to you, preferably someone who irritates you or causes you problems. Look mentally at this person and repeat: "They too are created in the image of God." Try to perceive, beyond the flaws or conflicts, this divine presence in them. If possible, make a concrete gesture of recognition: a smile, a kind word, a prayer for them.

Day Three: Gratitude for CreationGo out into nature, or simply look out the window at a tree, the sky, or an animal. Become aware of the goodness of creation, its free beauty. Thank God for this gift. Ask yourself: how can I better respect and protect this creation?

Fourth day: Offering of workAt the beginning of your workday, explicitly offer to God what you are going to accomplish. Consider your work, however humble, as participation in God's creative work. Strive to put your best into it, not out of stressful perfectionism, but out of respect for your creative vocation.

Day Five: Relationship InvestmentIdentify a relationship that needs attention or repair. Spend quality time with that person: a phone call, a visit, a close listening ear. Remember that we are created for relationship, and it is in communion that we become fully human.

Day Six: Commitment to JusticeChoose a social or environmental justice cause that resonates with you. Learn more, support an organization financially, sign a petition, and spread the word. Recognize that defending human rights or creation is about honoring God's image in the world.

Seventh day: Sabbath rest. Give yourself a time of rest, without guilt. The Sabbath is not wasted time, but time dedicated to God and contemplation. Resist the temptation of productivism. Simply savor the fact of existing, of breathing, of being loved by God. This rest is itself an act of faith: it recognizes that we are not the absolute masters of our lives.

Conclusion

The Creation account in Genesis 1 is not a scientific text about the origins of the universe, but a theological proclamation about the identity and vocation of humanity. By affirming that human beings are created in the image of God, this text establishes a universal and inalienable dignity that grounds all authentic ethics. This truth, far from being abstract, has revolutionary implications for our personal, social, and ecological lives.

Recognizing the image of God in every human being transforms our view of ourselves and others. This prohibits all discrimination, all exploitation, all violence. It calls for radical respect for the person, from conception to natural death, regardless of their abilities or status. This perspective is the foundation of the struggle for social justice, human rights, and gender equality.

Embracing our creative and relational vocation gives meaning and dignity to our daily existence. Our work is no longer a chore, but rather a participation in the divine work. Our relationships are no longer optional, but constitutive of our humanity. We are called to create, to beautify, to order, while remaining open to others and cultivating communion.

Taking our ecological responsibility seriously commits us to transforming our relationship with nature. The earth is not a storehouse of resources to be exhausted, but a sacred garden to be cultivated and cared for. This responsibility, far from being a burden, connects with our deepest vocation as faithful stewards of creation. It invites us to joyful sobriety, admiring contemplation, and a concrete commitment to safeguarding our common home.

But let's be honest: fully living this image-based vocation is beyond our strength. Sin has disfigured the divine image within us. We are incapable, on our own, of fully honoring our dignity. This is why the story of Genesis must be reread in the light of Christ. He, the perfect Image of the Father, comes to restore the damaged image within us. By becoming incarnate, by assuming our humanity, he reveals what we are called to become. By dying and rising again, he opens the way to a new creation.

The call addressed to us today is therefore twofold. On the one hand, to gratefully acknowledge the extraordinary dignity bestowed upon us from the beginning. We are images of God! This truth should fill us with wonder and responsibility. On the other hand, to welcome the work of Christ who comes to accomplish in us what we cannot accomplish alone. By baptismal grace, we are configured to Christ, become participants in the divine life, and begin now to live the fullness of our image-based vocation.

May this story from Genesis not remain a dead letter, but become a leaven of transformation in our lives! May it inspire our prayer, guide our choices, and guide our commitments! May it make us joyful witnesses of human dignity, artisans of justice and peace, vigilant guardians of creation! For by honoring the image of God in us and around us, it is God himself that we glorify.

Practical

Daily meditation : Every morning, repeat three times: “I am created in the image of God” to anchor your dignity in your consciousness.

Contemplative gaze : Before judging or criticizing someone, remember: “This person is the image of God.”

Spiritual Ecology : Adopt a concrete ecological practice this week (waste reduction, composting, water saving) by experiencing it as a spiritual act.

Offering of work : As you begin your work, say: “Lord, I offer you what I am going to accomplish today as a participation in your creative work.”

Relationship investment : Spend quality time each day with someone close to you, without distractions (phone off, full presence).

Solidarity commitment : Choose a social or ecological justice cause and support it concretely (donation, volunteering, awareness).

Weekly Sabbath : Set aside half a day a week for rest, prayer, contemplation, without guilt or productivity.

References

Biblical text : Genesis 1,20 – 2,4a (priestly account of creation), Jerusalem Bible or Liturgical Translation of the Bible.

Patristic : Irenaeus of Lyon, Against heresies, Book V (image/resemblance distinction); Gregory of Nyssa, The Creation of Man (theological anthropology).

Medieval Theology : Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, Ia, q. 93 (On the image and likeness of God in man).

Contemporary Magisterium : Vatican Council II, Gaudium et Spes, § 12-22 (dignity of the human person); Pope Francis, Laudato si' (2015), encyclical on the safeguarding of the common home.

Contemporary Theology : Karl Barth, Dogmatic, § 41 (Man created by God); Hans Urs von Balthasar, Glory and the Cross, volume I (theology of the image).

Biblical commentaries : Claus Westermann, Genesis 1-11: A Commentary (in-depth exegetical analysis); André Wénin, From Adam to Abraham or the wanderings of humanity (narrative and theological reading).

Spirituality : Jean-Yves Leloup, Taking care of the being (spirituality of the divine image); Anselm Grün, The image of God in us (practical meditations).