Gospel of Jesus Christ according to Saint Luke

At that time,

while he was making his way towards Jerusalem,

Jesus went through towns and villages teaching.

Someone asked him:

"Lord, are only a few people saved?"

Jesus said to them:

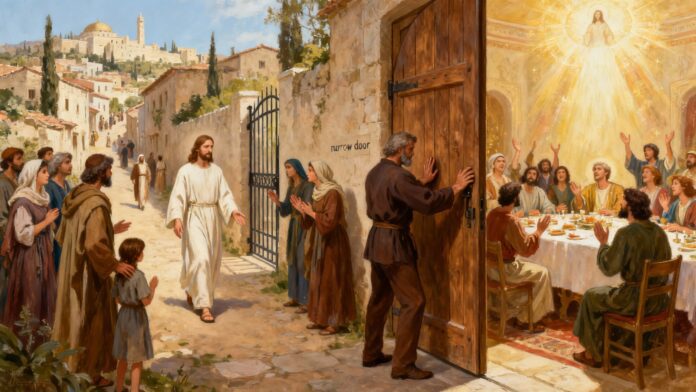

"Strive to enter through the narrow gate,

For, I tell you,

many will seek to enter

and will not succeed.

When the master of the house has gotten up

to close the door,

If you, from the outside, start knocking on the door,

saying:

“Lord, open to us”,

He will answer you:

“I don’t know where you’re from.”

Then you will start saying:

“We ate and drank in your presence,

and you taught in our town squares.”

He will answer you:

“I don’t know where you’re from.

Get away from me,

all of you who commit injustice.”

There will be tears and gnashing of teeth there.

when you see Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, and all the prophets

in the kingdom of God,

and that you yourselves will be thrown out.

So we will come from the east and the west,

from the north and the south,

to take their place at the feast in the kingdom of God.

Yes, there are those who are last who will be first.

and the first will be last.

– Let us acclaim the Word of God.

Enter through the narrow gate and taste God's feast

How to live out today the promise of the Kingdom which welcomes all nations and all personal stories.

In a world at a breakneck pace, saturated with information and moral anxieties, Jesus' call to "enter through the narrow gate" resonates with particular urgency. The Gospel of Luke 13:22-30, initially mystifying, becomes for the believer an invitation to vigilance and joy. Through the image of the feast, it reveals a hospitable, patient, and universal God. This article offers a progressive and embodied reading of this text: its context, spiritual dynamics, concrete consequences, and paths of practice to experience the opening of the Kingdom even now.

- Understanding the context of the crossing and the tension towards Jerusalem.

- Deploying the heart of teaching: effort, openness and reversal.

- Explore the theological, social and inner resonances.

- Connecting the parable to our personal and community practices.

- Conclude with a living prayer and a spiritual action journal.

Context

Luke's Gospel occupies a unique place in the Synoptic Gospels: it is the Gospel of journeying, mercy, and the peripheries. The scene unfolds "as Jesus was traveling toward Jerusalem." This detail is not insignificant: it situates the message within a dynamic movement. Jesus teaches while moving forward, passing through towns and villages—that is, the most diverse human realities. Where other evangelists focus on controversies or miracles, Luke captures Jesus in the pedagogical act of the traveler.

The question suddenly arises, a typically human one: “Lord, are only a few people saved?” But Jesus doesn’t give in to statistical curiosity: he shifts the question from “how many” to “how.” Access to salvation is not a quantifiable fact; it’s a path that requires personal commitment: “Strive to enter through the narrow gate.”

This verb, "to strive", translates the Greek agonizesthe, root of the word "agony" and "struggle". Entering the Kingdom becomes a peaceful struggle: that of fidelity and perseverance.

The scene then changes: the door closes, the characters knock outside. The image evokes the parables of the wise virgins, the wedding feast, and Noah. The tragedy is not divine wrath, but the inner distance of those who have been with Jesus without truly recognizing him: “We ate and drank in your presence…” The conviviality was not enough; the conversion of heart was lacking.

Then comes the great opening: “People will come from the east and the west…” Salvation overflows the borders of Israel; the feast becomes universal. Those excluded by appearances of piety, the last, will be first in the communion of the Kingdom. Thus, the text unfolds a twofold movement: intimate demand and total openness, spiritual rigor and vast divine hospitality.

Analysis

At the heart of this Gospel, a fruitful tension exists between the narrow gate and the open table. Jesus preaches neither religious exclusivism nor moral relativism: he combines demanding standards with generosity. The "narrow gate" is not a code reserved for a select few; it is the vigilance of a sincere heart, free from illusions.

This requirement only makes sense because it leads to the feast, a symbol of shared joy. The biblical feast recalls Abraham's under the oak of Mamre, where three mysterious visitors represent the divine presence; or the wedding feast of Isaiah: a banquet for all peoples. Luke, a disciple of Paul, expresses the same insight here: faith is recognized by its openness.

The analysis of the passage thus reveals three poles:

- Personal effort, not as competition, but as free direction.

- The rejection of religious appearances, which masks the lack of justice.

- The universality of salvation, a fruit of grace rather than merit.

Understanding this text means overturning our instinctive categories: good churchgoers are not automatically "in," and outsiders can find themselves first in the Kingdom. This reversal directly links Jesus' message to the experience of the Church: the proclamation of the Gospel calls us to overcome divisions in order to participate in the divine feast.

The narrow gate: a symbol of spiritual maturity

Entering through the narrow gate means learning to choose. In a world where everything is spread out, the narrow gate forces us to define what is essential. It constricts the passage to purify desire: only confident faith passes through unimpeded.

Luke does not present this narrowness as a punishment, but as an inner adjustment. The disciple battles his demons of pride, habit, and superficiality. In the Psalms, "the gates of righteousness" open to those who acknowledge their poverty. Luke's "narrow gate" corresponds to this dynamic: less an obstacle than a condensation of the heart. It recenters life, tracing the path toward true joy.

In the monastic tradition, this gate is compared to the inner cloister: the soul learns to renounce its scattered nature in order to be unified in the presence of God. This experience concerns every believer: entering through the narrow gate means choosing love when everything encourages indifference, fidelity when everything urges flight, and trust when fear prevails.

The Feast of the Kingdom: Joy Extended

Once this passage is crossed, the Gospel shifts to the image of the great banquet. Throughout the Bible, this is the most consistent symbol of communion. Jesus eats with sinners, multiplies the loaves, and washes feet during the Last Supper. The feast of the Kingdom already finds its foretaste here below: each Eucharist anticipates the table of the end times.

What does "People will come from the east and the west" mean? First, the promise of universal gathering: no people are excluded. But more profoundly, it designates the inner dimensions of being: the east of the heart (where Christ rises like the sun) and the west of shadow (our wounded areas) come together in the same reconciliation.

The banquet then becomes a space where all wounds heal, where difference ceases to be a threat. It assumes that each person arrives not armed with merit, but with an open heart. A place at the feast is not reserved; it is received with gratitude.

The first and the last: the logic of reversal

This conclusion, common in Luke, situates the Gospel within a prophetic dynamism: God cannot be confined by our hierarchies. The last becomes first not through revenge, but through grace: God restores to the despised their highest dignity.

This reversal challenges our social and religious practices. In the Christian community, who is considered "first"? Those who master the liturgical language? Those who serve in silence? Jesus shifts the criterion: true priority belongs to those who love unconditionally. The ultimate hierarchy of the Kingdom is that of free hearts.

Applications

Applying this principle means combining effort and openness in four spheres of life:

Personal life. Entering through the narrow gate means choosing consistency. For example, keeping one's word, renouncing duplicity, maintaining a prayer life even when austere. This inner struggle structures freedom: faith ceases to be merely emotion or ritual.

Family and social life. The feast of the Kingdom begins at the table. A family united despite disagreements becomes an icon of the divine banquet. Sharing the meal with patience and gratitude is already entering the Kingdom.

Social life. The text sheds light on justice: God reproaches those who "commit injustice." Entering through the narrow gate means rejecting destructive compromises: in work, preferring integrity to unjust success; in the city, promoting an inclusive way of living together where no one is left out.

Church life. The narrow gate calls for purifying communal faith of self-satisfaction. The Church, a visible sign of the Kingdom, must constantly reopen its doors to the East and the West: migrants, seekers, the wounded—everyone has a place at the banquet. The text thus becomes a framework for pastoral reinterpretation: how do we live out welcome, mercy, and joy?

Tradition

The call to the narrow gate resonates throughout early Christianity. The DidacheIn a catechetical text from the 1st century, there are "two paths: that of life and that of death." Choosing life means walking in the narrow path of light.

The Church Fathers often speak of the final feast: Irenaeus of Lyons sees in it "the consummation of all justice." Augustine, more introspective, emphasizes that the narrow gate is not external: "Narrow is the passage, for vast is your heart when it loves." Thomas Aquinas reads in it the perfection of charity: constricted in the face of sin, wide in the face of grace.

In the liturgical tradition, this passage from Luke is often associated with the time of the pilgrim. It also resonates with mystics: Teresa of Avila speaks of the "little passage of humility" that leads to the hall of the inner banquet. Francis de Sales translates it thus: "Love becomes simpler as we move forward."

Finally, in contemporary spirituality, the popes have taken up this theme. Francis, in Evangelii GaudiumHe emphasizes that the Church must be "a house with open doors," not an exclusive club. The narrow gate of discipleship becomes the wide-open gate of mercy.

Spiritual meditation

Entering through the narrow gate can become a seven-day spiritual exercise.

- Day 1: Identify the doors that are too wide in my life: habits, distractions, selfishness.

- Day 2: To name the narrow gate: where a concrete conversion is required of me.

- Day 3: To reread a shared meal and recognize the presence of Christ in it.

- Day 4: Meditating on the "last ones": those who, in my environment, remain on the margins.

- Day 5: To offer a prayer of gratitude for the universality of salvation.

- Day 6: To perform a discreet act of justice or hospitality.

- Day 7: To participate in a Eucharist with awareness, as a foretaste of the feast to come.

This simple and rhythmic practice transforms faith into an attitude. The Kingdom draws near in every gesture of openness lived in faithfulness.

Current challenges

Today, the narrow gate is off-putting. In a society where "everything is accessible," it seems authoritarian. But reread in the light of the Gospel, it becomes a pedagogy of freedom: knowing how to choose truth over ease.

First challenge: moral relativism. How can we reconcile openness and high standards? The Gospel does not advocate weak tolerance, but truth in charity. The gate is narrow not because it excludes, but because it purifies.

Second challenge: spiritual fatigue. Many feel exhausted in their faith, caught between obligations and doubts. Yet, the effort required is not performance: it is humble perseverance. Like an athlete of peace, the disciple trains to love over time.

Third challenge: the crisis of universality. The feast of all nations is being tested by the rise of identity politics. How can we believe in a Kingdom where cultures and opinions coexist? Luke's answer: by proclaiming a God who never humiliates, but lifts each person up in their uniqueness.

The passage thus calls for a mature Christianity: personal, embodied, missionary. It encourages a cultural conversion: moving from a faith of refuge to a faith of sending forth.

Prayer

Lord Jesus,

You who walked towards Jerusalem, make us walk with You.

In our hesitations, keep our hearts faithful and vigilant.

When the door seems too narrow, remind us that your love guides us.

When the table seems too large, teach us to welcome without fear.

Make us companions at the feast,

Where East and West greet each other,

Where the first welcome the last.

Where joy triumphs over all closure.

Give us the grace to knock on the door today,

Not to beg for a place,

But to enter with everyone into your light.

May your Church, gathered from the four winds,

A sign of unity, shared bread, an open house.

You who live and reign, today and forevermore.

Amen.

Conclusion

The Gospel of Luke 13:22-30 reveals itself as a golden thread between the rigor of the journey and the promise of a universal feast. Jesus opens a pedagogy of the heart: to strive to enter, not out of fear of being rejected, but to become capable of loving.

To live this chapter is to rediscover the balance between inner strength and openness to community. Each person is invited to cross the threshold each day: the threshold of prayer, patience, and forgiveness. Then the table of the Kingdom is quietly extended into our homes, our relationships, our communities. There, the promised feast is already tasted.

Practical

- Identify a personal "narrow door" this week and stay true to it.

- Read the passage from Luke 13:22-30 aloud every morning.

- Sharing a symbolic meal with someone unexpected.

- To offer a concrete act of welcome or forgiveness.

- Pray for the unity of peoples and churches.

- Keep a daily journal of spiritual gratitude.

- Participating in a liturgy by meditating on the symbolism of the feast.

References

- The Jerusalem Bible, Luke 13:22-30.

- Irenaeus of Lyon, Against heresies, IV,20.

- Augustine, Sermons, nos. 47-49.

- Francis de Sales, Treatise on Divine Love.

- Pope Francis, Evangelii Gaudium (2013).

- The Didache, chapters 1-5.

- Teresa of Avila, The Interior Castle.

- Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, IIa-IIae, q.184.