Reading from the Letter of Saint Paul the Apostle to the Romans

Brothers,

sin must not reign in your mortal body

and make you obey his desires.

Do not present the members of your body to sin

as weapons in the service of injustice;

on the contrary, present yourselves to God

like the living returned from the dead,

present your members to God

as weapons in the service of justice.

For sin will no longer have dominion over you:

for you are no longer subject to the Law,

you are subjects of God's grace.

So? Since we are not subject to the Law

but to grace,

are we going to commit sin?

No way.

Don't you know?

The one to whom you present yourselves as slaves

to obey him,

it is from him, to whom you obey,

that you are slaves:

either from sin, which leads to death,

either obedience to God, which leads to righteousness.

But let us give thanks to God:

you who were slaves of sin,

you have now obeyed with all your heart

to the model presented by the teaching that has been transmitted to you.

Freed from sin,

you have become slaves to righteousness.

– Word of the Lord.

Come Alive: The Inner Revolution of Grace According to St. Paul

How to move from the slavery of sin to the radical freedom of the resurrected

In his letter to the Romans, Saint Paul issues a moving appeal: to present ourselves to God as resurrected. This invitation is not a pious metaphor, but a program of radical transformation. Faced with the Christians of Rome tempted by moral compromise, the apostle reveals a liberating truth: grace does not dispense with ethics; it finally makes it possible. For every believer seeking to live their faith authentically, this passage offers a decisive key: understanding that the Christian life is not a heroic moral effort, but a rebirth that engages our whole being in the fight for justice.

After situating this text within the great Pauline debate on grace and the Law, we will explore the central paradox: Christian freedom becoming voluntary servitude. We will then unfold three major axes: the resurrection as a present event, the body as a spiritual territory, and liberating obedience. Finally, we will listen to the resonances of this word in the Christian tradition before proposing concrete avenues for putting it into practice.

Context

Chapter 6 of the Epistle to the Romans constitutes a pivotal moment in Saint Paul's argument. Having established in the preceding chapters that salvation comes from faith alone and not from works of the Law, the apostle anticipates a formidable objection: if grace abounds where sin has abounded, why not continue to sin so that grace may be manifested more? This question, which might seem absurd, in reality reveals a permanent temptation: that of transforming Christian freedom into moral license.

Paul wrote to the Romans around the year 57-58, from Corinth, to a community he had not yet visited but whose tensions he was aware of. Rome was then home to a composite Church, bringing together Judeo-Christians attached to the Torah and recently converted pagan Christians. The question of the articulation between grace and morality was not a matter of theological speculation but touched on the daily lives of these believers: how to live as Christians in the capital of the Empire, surrounded by pagan temples and immoral practices?

The passage before us is part of a tight demonstration. Paul has just explained that through baptism, the Christian dies and is resurrected with Christ. This union with the crucified and resurrected Christ is not symbolic: it brings about an ontological break with the old life. The old man was crucified with Christ so that the body of sin might be destroyed. From now on, the baptized person belongs to a new order, that of the resurrection.

In our excerpt, the apostle draws practical consequences from this theological truth. He uses striking martial vocabulary: the members of the body are described as weapons that can be put to the service of opposing camps. This militarization of language is not accidental. Paul, a Roman citizen, is well acquainted with the legionary organization and uses this imagery to show that neutrality is impossible: one necessarily serves a master, either sin, which leads to death, or God, who leads to righteousness.

The rhetorical structure of the passage reveals Pauline pedagogy. First, a negative imperative: do not let sin reign. Then a double movement: do not present your members to sin, but present yourselves to God. Next, a theological justification: you are no longer under the Law but under grace. Then an anticipated objection and its refutation. Finally, an act of thanksgiving and a description of the believer's new condition.

This text belongs to the genre of moral exhortation, but it is distinguished from simple parenesis by its Christological and baptismal anchoring. Paul does not propose a natural morality accessible through reason, but an ethic rooted in the paschal event. Moral transformation flows from the mystical union with Christ. It is this articulation between theological indicative and ethical imperative that makes Pauline morality unique and powerful.

Analysis

The heart of our passage lies in a paradoxical statement that overturns all our categories: true freedom consists in becoming a slave to God. To understand this reversal, we must grasp Paul's anthropological vision. Man never exists in a state of absolute autonomy. He is always already engaged in a relationship of dependence. The only question is: to whom does he belong?

This thesis is in direct opposition to the ideal of autonomy that structures Greek thought and, later, modernity. For Paul, the demand for radical independence constitutes precisely the supreme form of alienation. By refusing to serve God, man does not conquer his freedom: he submits to sin, a far more implacable tyrant. Sin, in Pauline theology, is not primarily a moral fault, but a cosmic power that enslaves humanity. It is a personal, almost personified force that reigns and causes death to reign.

The dynamics of the text reveal a three-stage liberation movement. First stage: awareness. Paul challenges his readers: Don't you know? This rhetorical question assumes that the truth is already known but not fully appropriated. The Christian possesses saving knowledge, but must allow it to transform his concrete existence. Second stage: thanksgiving. Let us give thanks to God: liberation does not come from human effort but from divine initiative. It calls for gratitude, not pride. Third stage: practical reorientation. Present yourself to God: the freedom acquired must be activated by a daily choice.

The most striking expression remains that of the living returned from the dead. Paul does not say: present yourselves as living people who avoid death, but as living people who have already passed through death and returned. This nuance is crucial. It signifies that the Christian life is not an escape from death, but a life conquered over death, a life that has passed through death and emerged victorious. Baptism brought about this crossing: immersed in the death of Christ, the believer rises to a new life.

This new life has a quality different from ordinary biological existence. It already participates in eternal life; it is life according to the Spirit, life oriented toward God. Hence the ethical requirement that naturally follows from it: since you have been resurrected, live as resurrected people. The imperative stems from the indicative. It is not: strive to be resurrected by living morally; it is: because you have been resurrected, the moral life becomes possible and necessary.

The contrast between Law and grace illuminates this new possibility. Under the Law, man knew good but could not accomplish it. The Law revealed sin without providing the strength to overcome it. It prescribed but did not transform. Grace, on the contrary, changes the condition of the moral subject. It does not simply indicate the path; it gives the ability to follow it. It creates a new man, capable of an obedience that is no longer external constraint but internal adherence.

The Resurrection: A Present Event, Not a Future Event

When Paul speaks of the living returning from the dead, he does not project this resurrection into a distant afterlife. He asserts that it has already occurred, sacramentally, in the waters of baptism. This assertion disturbs our tendency to relegate the great Christian promises to a comfortable eschatological future. The resurrection is not just the hope that consoles; it is the reality that transforms today.

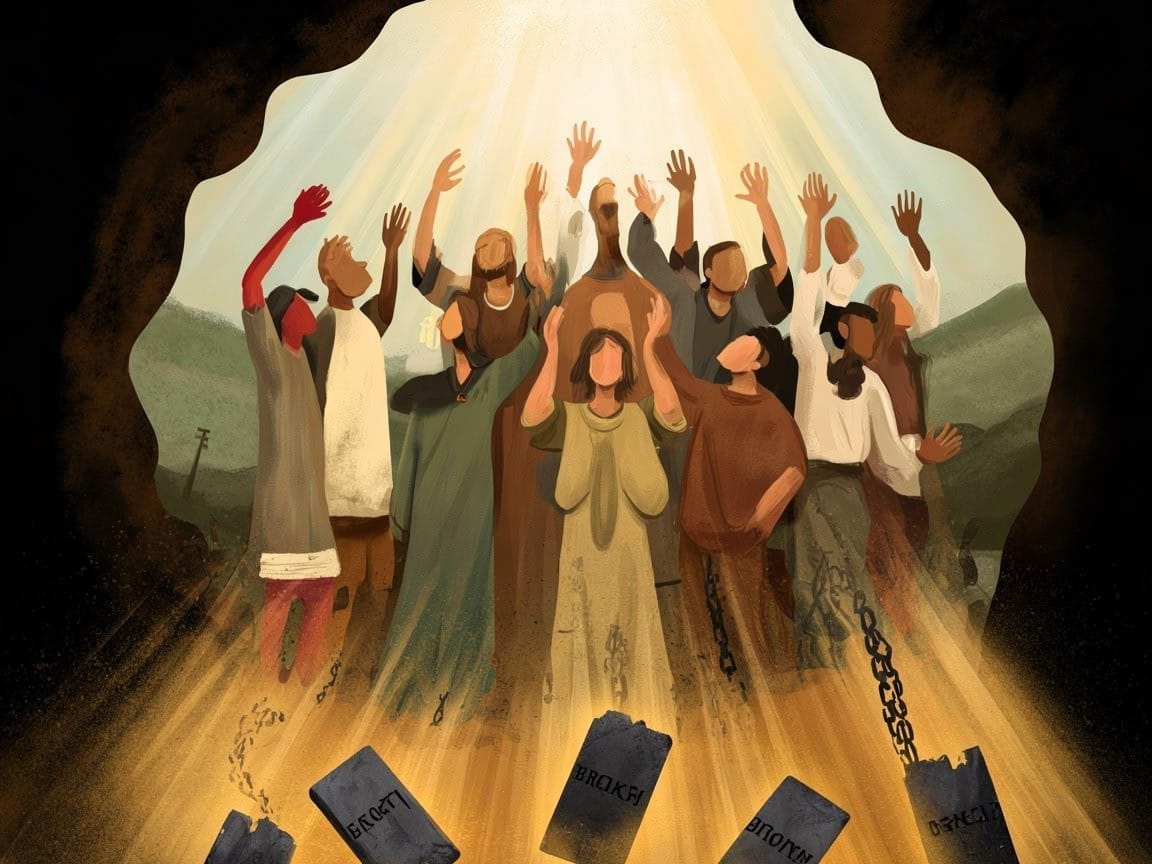

This relevance of the resurrection explains the urgency of Paul's call. If we have already been resurrected, then every moment we live according to the ancient logic of sin constitutes an unbearable contradiction. It is as if a freed prisoner chose to remain in his cell. The door is open, the chains are broken, but we must dare to cross the threshold, to truly inhabit the freedom we have won.

The Fathers of the Church have magnificently developed this theology of the present resurrection. For them, the Christian lives between two resurrections: that of baptism, already accomplished, and that of the flesh, still awaited. Between the two extends the time of the Church, a time of growth towards the full manifestation of what is already given in embryo. Saint Augustine compares this situation to that of an heir who already possesses the title of property but has not yet entered into the enjoyment of his inheritance.

Concretely, living as a resurrected person means adopting the behavior of one who no longer fears death. The martyrs illustrated this logic to the very end: for those who have already passed through death with Christ, physical death loses its sting. It becomes a passage and not a rupture. But this victory over death is also exercised in the small daily deaths: agreeing to renounce one's unjust privileges, forgiving instead of taking revenge, giving without calculating the return. Each of these acts proclaims: I live a life that no longer fears death.

The present resurrection also transforms our relationship with time. It introduces a dimension of eternity into chronological time. The resurrected one already inhabits the Kingdom while still walking on this earth. He is a citizen of two cities, but his true homeland is heavenly. This dual belonging does not lead to contempt for the earthly world; on the contrary, it is because he already participates in eternal life that the Christian can fully commit himself to justice in history, without being crushed by absurdity or despair. He knows that death does not have the last word, that love is stronger, that good will triumph.

This active hope radically distinguishes the Christian from the naive optimist and the disillusioned pessimist. He is not ignorant of evil; he even observes its massive power in history and in hearts. But he knows that evil has already been defeated, even if the victory is not yet fully manifest. He therefore fights with the certainty of the soldier who knows the outcome of the war is already decided, even if battles remain to be fought.

The body: spiritual territory and battlefield

Paul uses a very precise bodily vocabulary. He does not speak of the soul or spirit in opposition to the body, but of the body's members as instruments that can be directed. This attention to the body deserves attention, because it contradicts the dualism that has often contaminated Christian spirituality.

For the apostle, the body is not the prison of the soul; it is the very place of spiritual life. It is with his body that the Christian serves God or sin. Bodily members—hands, feet, mouth, eyes—become weapons in spiritual combat. This military vocabulary indicates that the body is a battlefield, a territory contested between two opposing kingdoms.

This vision has immense practical consequences. It means, first of all, that holiness is not a matter of pure intentions but of concrete actions. What I do with my body engages my spiritual destiny. Gestures matter: where I take my steps, what I touch with my hands, the words that come out of my mouth. Christian morality is not idealistic; it is incarnate. It does not despise matter but takes it seriously as a place of obedience or rebellion.

This approach then values the bodily practices of spirituality: fasting, almsgiving, pilgrimage, prostration, liturgical gestures. These practices are not folkloric accessories; they are ways of concretely presenting one's body to God. When I kneel to pray, my body confesses that God is great and I am small. When I stretch out my hand to give alms, my arm becomes an instrument of divine charity. When I abstain from food to fast, my stomach learns spiritual mastery.

This theology of the body also sheds light on Christian sexual morality, so often misunderstood. If the body is a member of Christ, a temple of the Holy Spirit, then certain uses of the body become impossible not out of puritanism but out of ontological coherence. One cannot unite the members of Christ with a prostitute, Paul already told the Corinthians. It is not that sexuality is bad, it is that it so engages the body that its meaning goes far beyond simple physical pleasure.

Pauline wisdom about the body is equidistant from two opposing errors. On the one hand, angelism, which would ignore the body and live a disembodied spirituality. On the other, materialism, which reduces man to his biological body and denies any transcendent dimension. Paul affirms: your body is destined for resurrection, it is called to participate in divine glory, so treat it with the respect due to a sanctuary while recognizing that it must be subject to the spirit.

Liberating Obedience: The Paradox of Voluntary Servitude

The most paradoxical Pauline formula remains this: freed from sin, you have become slaves of righteousness. How can slavery be freedom? Isn't this a contradiction in terms? To understand this paradox, we must distinguish between two types of servitude.

The first servitude, that of sin, is endured. No one deliberately chooses to be a slave to evil. We fall into it, we slide into it, we get bogged down in it. Saint Augustine described this state magnificently in his Confessions: I wanted good but I did evil, chained by my habits, prisoner of my passions. This servitude to sin is characterized by compulsion, alienation, and loss of self-control. Sinful man is not free; he is carried away by his desires, manipulated by his fears, determined by his addictions.

The second servitude, that of justice, is chosen. It is a free obedience, a voluntary submission. It resembles the commitment of the musician who submits to the rules of harmony not out of constraint but because he knows that this discipline is a condition of his creative freedom. Or again, to the athlete who subjects himself to rigorous training because he aims for victory. In both cases, the accepted rule liberates rather than alienates.

Paul specifies: you have obeyed with all your heart the model presented by the teaching. Christian obedience is not blind submission to arbitrary authority. It is cordial adherence to a model, that of Christ. The Greek word for model evokes an imprint, a seal that leaves its mark. The baptized person receives the imprint of Christ, is configured to him, becomes his image. From then on, obeying Christian teaching means becoming fully oneself, realizing one's deepest vocation.

This liberating obedience manifests itself in the concrete choices of life. Every time I choose truth over convenient lies, I free my speech from the bondage of deception. Every time I choose fidelity despite the lure of easy adventure, I free my capacity to truly love. Every time I practice justice instead of seeking my own interest, I free myself from the selfishness that constricts me.

The Christian spiritual tradition has developed an entire pedagogy of obedience. Monastic vows of obedience aim precisely at this paradoxical freedom. By renouncing self-will, the monk discovers the true freedom of God's children. He learns to will what God wills, and in this unification of will, he finds peace. It is no longer the perpetual war between what I must do and what I want to do. It is the harmony between desire and duty.

For the Christian in the world, this liberating obedience is exercised differently but according to the same logic. It involves presenting one's choices, decisions, and actions to God every day, aligning them with the divine will known by conscience, Scripture, and the teaching of the Church. This daily presentation gradually creates a second nature, a habit of holiness. What was effort becomes spontaneity, virtue matures into wisdom.

Tradition and sources

The Pauline theology of liberating grace has profoundly influenced the entire Christian tradition, particularly through two major figures: Saint Augustine and Martin Luther. Augustine, in his controversy against the Pelagians, developed the doctrine of efficacious grace that truly transforms the human will. For him, grace is not merely an external aid to moral effort; it is an interior force that heals the will wounded by sin and makes it capable of truly loving God.

Augustinian writings on Christian freedom echo Paul's dialectic exactly. In his treatise On Grace and Free Will, Augustine explains that true freedom is not the power to choose between good and evil, but the ability to no longer be able to sin. This libertas a necessitate peccandi, freedom from the necessity of sinning, characterizes the blessed in heaven and, in an anticipated way, those who live under grace.

Thomas Aquinas, in the 13th century, integrated this perspective into his theological synthesis. In the Summa, he distinguished between libertas a coactione, the external freedom from constraint that even the sinner possesses, and libertas a miseria, the internal freedom from the misery of sin, which only grace provides. For Thomas, perfect virtue sets one free because it brings will and duty into line: the virtuous person spontaneously does the good he loves.

The Christian mystical tradition has explored the practical dimensions of this freedom in grace. John of the Cross speaks of the self-emptying necessary for God to act fully. Teresa of Avila describes the dwellings of the inner castle where the soul progresses toward transforming union. Francis de Sales teaches the sweetness of loving obedience. In all these great spiritual figures, we find the Pauline theme: to surrender oneself totally to God is to find true freedom.

The baptismal liturgy of the ancient Church perfectly illustrates our passage. The ritual included a triple renunciation: I renounce Satan, his pomps and his works, followed by a triple profession of faith: I believe in the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. This double movement responds exactly to the Pauline exhortation: do not present yourselves to sin, present yourselves to God. Baptism brings about this transfer of allegiance, this radical metanoia that changes master.

The Greek Fathers developed a theology of divinization that extends Paul's thought. For them, to be freed from sin and become slaves to righteousness is to participate in the divine nature. Grace does not simply leave us improved humans; it divinizes us, it makes us theoi, gods by participation. This theological boldness is rooted in the conviction that Christ's resurrection opened up an unprecedented destiny for humanity: to become what God is by nature.

Meditation

To concretely embody Saint Paul's call to present ourselves to God as resurrected people, here is a spiritual journey in seven stages, progressive and realistic:

First step : Every morning, upon waking, realize that this day is a gift. Say to yourself: I am alive, risen with Christ. This day is given to me to serve justice. This morning awareness guides the entire day.

Second step Concretely identify the parts of your body that you will present to God today. Where will my feet go? What will my hands do? What will my lips say? Present them explicitly to the Lord in a brief prayer.

Third step : In times of temptation or difficult decision, remember your baptism. Inwardly renew your renunciation of Satan and your profession of faith. This gesture can be accompanied by the sign of the cross, a baptismal memorial.

Fourth step : Practice a form of fasting or abstinence, even modest, to physically experience that you are not a slave to your desires. This can be a food fast, but also a media or digital fast.

Fifth step : Choose a concrete act of justice each week. Give alms, visit a sick person, defend someone who has been unjustly attacked. Make your members weapons in the service of justice.

Sixth step In the evening, make a brief examination of conscience by reviewing the members of the body. How did my eyes look today? Did my hands serve? Did my mouth edify? Give thanks for victories, ask forgiveness for falls.

Seventh step : Once a week, take a longer time to meditate on our passage from Saint Paul. Read it slowly, stop on a sentence that particularly resonates, ruminate on it, ask the Holy Spirit to move it from the mind to the heart, then from the heart to actions.

Conclusion

Saint Paul's appeal to the Romans resonates today with renewed urgency. In a world that confuses freedom with license, that reduces autonomy to absolute independence, the apostle's words offer a paradoxical path of liberation: true freedom is found in the gift of oneself to God. It is not one more form of enslavement; it is the escape from all forms of slavery.

Living as a resurrected person is not a matter of impossible moral heroism, but of welcoming transforming grace. The inner revolution that Saint Paul proposes is not a gradual improvement of the old man; it is a radical rebirth. Baptism has made us new creatures. Now it is a matter of letting this newness invade every corner of our existence: our thoughts, our desires, our choices, our relationships, our commitments.

To present one's body to God as a living being returned from the dead is to make every daily gesture an act of resurrection. It is to inscribe in the flesh of the world the victory of Christ over death. It is to bear witness that love is stronger than all the powers of destruction. It is to affirm, against the evidence of evil that disfigures history, that light has already conquered darkness.

This resurrected life transforms society. Men and women who no longer fear death become invincible in their fight for justice. They can take all the risks of love because they no longer calculate according to the logic of the world. They are free with the very freedom of God, this freedom that gives itself without counting, that forgives without limit, that hopes against all hope.

Paul's invitation is therefore a revolutionary call. An inner revolution first: to let God reign in us rather than sin. But also an outer revolution: to transform the world by introducing the logic of the Kingdom, this logic where the last are first, where to serve is to reign, where to lose one's life is to save it. This is the Christian vocation: to become living people who have passed through death, free people who have chosen obedience, slaves of justice who manifest the true freedom of the children of God.

Practical

- Resurrected Awakening : Begin each day by thanking God for the gift of life and renewing the offering of oneself in his service.

- Baptismal memory : Make the sign of the cross consciously, remembering that through baptism one died and rose again with Christ.

- Body examination : Every evening, review the actions of my members (eyes, hands, mouth) to discern whether they have served righteousness or sin.

- Practice of giving : Carry out a concrete act of charity or justice each week that involves the body: almsgiving, visits, service.

- Liberating Fasting : Practice a form of regular abstinence to learn mastery of desires and inner freedom from needs.

- Pauline Meditation : Read and slowly ruminate on Romans 6 each week, asking the Spirit to bring the Word into concrete life.

- Eucharistic celebration : Regularly participate in the mass where the paschal mystery is re-enacted, the source of our resurrection and our new freedom.

References

Main Biblical Sources : Epistle to the Romans, chapter 6; Epistle to the Galatians 5, 1-13 on Christian freedom; First Epistle to the Corinthians 6, 12-20 on the body as temple of the Spirit.

Patristic tradition : Saint Augustine, On Grace and Free Will; Saint John Chrysostom, Homilies on the Epistle to the Romans.

Medieval Theology : Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, Prima Secundae, Treatise on Grace; Bernard of Clairvaux, Treatise on Grace and Free Will.

Modern spirituality : Martin Luther, The Freedom of the Christian; John of the Cross, The Ascent of Carmel; Thérèse of Lisieux, History of a Soul.

Contemporary Commentaries : Romano Guardini, The Death of Socrates and The Death of Christ; Joseph Ratzinger (Benedict XVI), Introduction to Christianity; Hans Urs von Balthasar, The Divine Drama.

Exegetical studies : Stanislas Lyonnet, The Freedom of the Christian according to Saint Paul; Ceslas Spicq, Moral Theology of the New Testament.