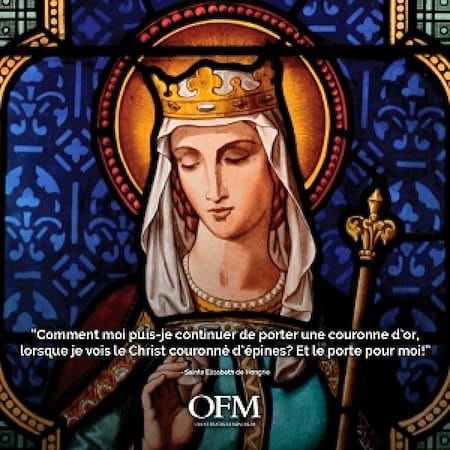

Elizabeth of Hungary (1207-1231) demonstrates how the exercise of power and wealth can be transformed into a radical service to the most destitute. A princess who became a member of the Franciscan Third Order, her short life in Thuringia and Hesse (GermanyThis illustrates a joyful charity, drawing its source from the love of the poor and crucified Christ. It questions our relationship to authority and material possessions, calling us to see the face of God in those who suffer, like the first Franciscans who inspired it. Her figure remains a powerful example of what faith can accomplish when it unites contemplation and concrete action.

Authority experienced as a radical service to the poor

Recognizing Christ in the face of the poor: this was the challenge posed by Saint Elizabeth of Hungary in the 13th century. This princess, Duchess of Thuringia, underwent a radical conversion after the death of her husband. Influenced by the ideal of Saint FrancisShe chose to relinquish her honors to dedicate herself entirely to the sick and the poor. Today, her memory challenges us on our ability to transform our positions of power, whether small or large, into opportunities for service and genuine charity, by uniting justice and mercy.

From the courtyard to the hospital, a life given

Elizabeth was born in 1207, likely in Pressburg (Bratislava). The daughter of King Andrew II of Hungary, she was, as was customary, at the heart of political alliances. At the age of four, she was betrothed to Louis, son of the Landgrave of Thuringia, in Germany central. She left her homeland to be raised at the Thuringian court, at Wartburg Castle.

What could have been a marriage of pure convenience transformed into a sincere union. The marriage was celebrated in 1221; Elizabeth was fourteen years old, and Louis was twenty-one. The accounts, particularly those reported by the Pope During a catechesis, Benedict XVI emphasized the "sincere love" between the couple, "animated by faith and the desire to fulfill God's will." They had three children. The couple was happy, and Louis actively supported his wife's deep devotion and her determined work on behalf of the poor.

Elizabeth's life took a dramatic turn in 1227. She was only twenty years old. Her husband, Louis, died of the plague in Italy while on crusade with Emperor Frederick II. Elizabeth was widowed and pregnant with her third child. Her situation changed abruptly. Her brother-in-law, Henry Raspe, usurped the government of Thuringia, accusing Elizabeth of being a bigot incapable of managing the royal patrimony.

Then began a period of radical hardship. Driven from the castle with her children in the dead of winter, she, a princess, had to seek refuge. Hagiography recounts that she was reduced to abject poverty, even finding shelter for a time in a pigsty. This ordeal, which she endured with patience and submission to God, stripped her of all social standing.

Thanks to the intervention of her uncle, the Bishop of Bamberg, the political situation calmed down. In 1228, Elizabeth received her widow's dowry. Attempts were made to remarry her, as was befitting her station. She categorically refused, now yearning for a different life. She chose to retire to Marburg, in Hesse.

It was there that she accomplished her major work. With her earnings, she founded a hospital dedicated to Saint Francis of Assisi, whose ideal of poverty had profoundly marked her through the first Franciscan friars who arrived in GermanyShe takes the habit of the Franciscan Third Order, becoming a consecrated woman in the midst of the world.

The last three years of her life were a total act of self-giving. She lived in a modest home near her hospital and personally dedicated herself to serving the sick and dying. She undertook the humblest and most repugnant tasks, caring for lepers, seeing in each wretched person the face of the poor and crucified Christ.

Elizabeth died of exhaustion and illness on November 17, 1231. She was only twenty-four years old. Her reputation for holiness was such that accounts of miracles at her tomb immediately poured in. Pope Gregory IX canonized her only four years later, in 1235.

The Miracle of Roses

Elizabeth's life is marked by established facts, but also by a collection of hagiographic accounts that aim to illustrate the radical nature of her charity. Distinguishing between history and legend allows us to grasp the spiritual significance of her figure.

A well-established historical fact is her devotion to the poor. Even during her time at the Thuringian court, and despite criticism from those around her who considered her behavior unworthy of her rank, Elizabeth personally distributed food to the needy, even drawing on the castle's reserves. She assiduously practiced works of mercy, visiting the sick and taking care of the deceased.

A famous legend, known as "the miracle of the roses," is associated with this charity. The story goes that one winter day, Elizabeth left the castle, her cloak filled with loaves of bread to the poor. She met her husband, Louis, or, according to other versions, her suspicious brother-in-law. He, astonished or annoyed by her activities, asked her what she was hiding. Elizabeth, perhaps fearful, replied, "They are roses." Intrigued in the dead of winter, he ordered her to open her cloak. When she obeyed, the loaves had miraculously transformed into a bouquet of magnificent roses.

The symbolic significance of this legend is immense. It does not primarily seek to prove a material fact, but to reveal a spiritual truth. The loaves of bread, fruits of human labor and earthly sustenance, are transformed into roses, symbols of divine love and grace. The miracle signifies that the act of charity (the bread) is, in God's eyes, an act of love (the rose). It legitimizes Elizabeth's actions against the criticisms of the court: her service to the poor is not a princess fantasy, but a work inspired by God.

Another element of hagiography is the account of her extreme downfall, particularly the episode in the pigsty. While it is certain that she was driven out and experienced great hardship, the starkness of the image serves to emphasize the Gospel reversal: the highest (the princess) takes the place of the lowest (the animals), in a radical imitation of the kenosis of Christ, himself born in a stable. These accounts, whether factual or symbolic, have constructed the memory of Elizabeth as that of a saint who chose poverty the most concrete, in the name of his love for God.

Spiritual message

The figure of Elizabeth of Thuringia is a powerful testament to authority experienced as service. As Benedict XVI emphasized, she is «an example for all those who assume responsibilities of government.» At every level, the exercise of authority must be experienced as a service to justice and to charity, in the ongoing pursuit of the common good.

Her Franciscan spirituality led her to not separate the love of God from the love of neighbor. She did not like poverty for herself, but she loved the poor because in them, she saw Christ. Her service was neither sad nor constrained. She said: "I do not want to frighten God with a gloomy face. Does he not prefer to see me joyful since I love him and he loves me?".

The concrete image she leaves us is that of her hands: the hands of a princess who refuse to wear a golden crown "when her God wears a crown of thorns," and who choose to wash the wounds of the sick.

Prayer

Saint Elizabeth, you who knew how to recognize Christ in the poorest and who left the honors of the world to become a servant of the sick, intercede for us.

Ask the Lord to give us your vision, to see the hidden suffering around us. Give us your strength, to bear trials and injustices with patience and hope. Obtain for us your zeal, to serve our brothers and sisters with joyful charity, never growing weary. Amen.

To live

- Spiritual gesture: Identify a person in our circle (family, work) who holds "authority" (parent, manager, elected official) and pray for 10 minutes that they will exercise it as a just and charitable service.

- Targeted service: Donate (food, clothing, money) to a local charity (Secours Catholique, Société Saint-Vincent-de-Paul) or give 30 minutes of your time for a street outreach program or a food bank.

- Self-examination: Tonight, reread the Gospel of Matthew 25:31-40 («I was hungry, and you gave me food…»). Ask myself: «Where have I encountered Christ today? Have I been able to recognize and serve him?»

Memory and places

The memory of Saint Elizabeth is particularly alive in Germany and within the Franciscan family.

The main place of his worship is the magnificent St. Elizabeth's Church (Elisabethkirche) in Marburg, in Hesse. Built by the Teutonic Order (with which it was closely associated) to house its relics from 1235, the year of its canonizationIt is one of the earliest and purest examples of Gothic architecture in GermanyIt immediately became a major pilgrimage center in the Christian West. Although its relics were dispersed during the Protestant Reformation, the tomb (relic) remains a central point of the church.

In France, Elisabeth of Hungary is the principal patron saint of the parish of Saint Elizabeth of Hungary (Paris, 3rd arrondissement), a church which also houses the worship of the Order of Malta.

She is the patron saint of Third Order Franciscan (today the Secular Franciscan Order) and, by extension, many charitable works, hospitals and nursing staff, due to her total devotion to the sick in the hospital she had founded.