In December 2025, a major study by the Pew Research Center set the record straight on a question that had been dominating the media for several months: are we really witnessing a religious revival in the United States? The short answer: no, not if we look at the national figures. But let's dig a little deeper, because the reality is more nuanced than a simple yes or no.

Imagine you read an article about a massive wave of conversions among young Americans. You turn on your television and see reports about Orthodox churches that can no longer accommodate all the new members. Then you come across this Pew Research Center study that says, "In fact, the numbers haven't changed in five years." Who to believe?

This is precisely the dilemma we face today. On one hand, captivating stories of young men who discover faith Orthodox on YouTube during the pandemic. On the other hand, statistics that show almost perfect stability. So, what's really going on?

What the numbers really say

The great stabilization

Let's start with the basic facts. Since 2020, approximately 70% of American adults report belonging to a religion. This percentage has remained virtually unchanged in five years. By 2025, 62% of Americans will identify as Christian, a figure almost identical to that of 2020.

You might be wondering, "Wait, does that mean religion isn't declining anymore?" Exactly. After decades of continuous decline—we're talking about from 1970 to around 2020—the decline has come to a complete halt. It's as if we've suddenly braked after a long descent.

To give you an idea of the scale of the previous change: in 2007, 84% of Americans identified with a religion. By 2020, that number had fallen to around 71%. That's a massive drop in just 13 years. But since 2020? Total stability. The figure has remained stuck around 70%.

The "nuns" have also reached a plateau.

Let's now talk about the group that generated so much discussion: the "nones," meaning those who don't identify with any religion. This group exploded, growing from 16 million in 2007 to around 29 million today. But guess what? That growth has also stopped.

The "nones" currently represent 29% of the adult US population. Among them, 5 identify as atheist, 6 as agnostic, and 19 describe their religion as "nothing in particular." These figures have not changed significantly since 2020.

It's fascinating when you think about it: for years, observers predicted that the number of "nuns" would continue to grow indefinitely. Some even envisioned a predominantly non-religious America within a few decades. But the movement has stopped. At least temporarily.

Young people: less religious, but not in continuous decline

Here's where it gets interesting. Young adults (18-30 years old) remain far less religious than their elders. Only 55% of them identify with a religion in 2025, compared to 83% of those over 71. The gap is enormous.

But – and this is crucial – this percentage of 55 % among young people has remained stable since 2020. It was 57 % in 2020, which represents minimal variation. No further drop, but certainly no rebound either.

Let's look at some concrete indicators: 32% of young adults pray daily (compared to 59% of older adults), and 26% attend religious services at least once a month (compared to 43% of older adults). These figures have also remained stable.

The special case of very young adults

Now, hold on tight, because this is where things get really nuanced. Pew researchers noticed something interesting: younger adults (18-22 years old, born between 2003 and 2006) are slightly more religious than those a few years older (23-30 years old).

For example, 30% of adults born between 2003 and 2006 report attending religious services at least once a month. This is more than the 24% observed among those born between 1995 and 2002.

Before you cry religious revival, let me explain what's really going on. This phenomenon isn't new at all. Researchers observed it in previous studies from 2007 and 2014 as well. Here's the pattern: very young adults (18-22 years old) tend to mirror their parents' religiosity for a few years after turning 18. Then, as they get older, their religious practice begins to decline.

It's as if, at 18-20 years old, you continue out of habit or respect for your parents. Then, as you gain independence and move away from home, you begin to forge your own path. Gregory Smith of the Pew Research Center is very clear: "Historical data suggests that the patterns we see today are the normal outcome of young adults possibly following their parents' religiosity for a few years after the age of 18, after which their religiosity begins to decline."«

In other words, this slight increase among 18-22 year olds probably doesn't mean they will remain religious. It's just a transitional effect towards adulthood.

The gender gap is narrowing (but not for good reasons)

Here's a surprising detail: among young adults, the traditional gap between men and women in terms of religiosity is narrowing. Historically, women Women have always been more religious than men. But among young people, this gap is narrowing.

Note that this isn't because young men are becoming more religious. It's because young women are becoming less so. In 2007, 54% of women aged 18 to 24 prayed daily, compared to 40% of men of the same age. Today, the two groups are much closer, but at a significantly lower level than before.

Among older generations, the gender gap remains significant. Women Women over 70, for example, are much more religious than men of the same age. But this difference gradually disappears in younger cohorts.

The contradictory signals that fuel the idea of a revival

The Orthodox phenomenon: real but microscopic

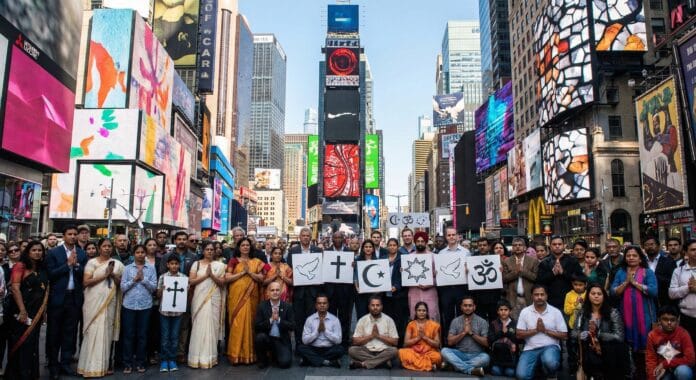

You may have seen those articles about a "tsunami" of young men converting to Orthodoxy. The New York Post, the Telegraph, and other media outlets have run enthusiastic reports on the subject. Orthodox priests claim their parishes are doubling in size. Articles tell of young men discovering faith on YouTube during the pandemic and who start fasting for 40 days straight.

These stories are true. They exist. But here's the problem: Orthodoxy remains a tiny tradition in the United States. There are approximately 300 million Orthodox Christians worldwide, but only a tiny fraction live in the United States.

And the Pew figures are unequivocal: only 1% of American adults aged 18 to 24 currently identify as Orthodox after being raised in another religion or with no religion at all. And get this: an equal percentage have left Orthodoxy. So the flow is neutral.

Trevin Wax, a religious observer who has analyzed these trends, explains it well: "Orthodoxy is a tiny tradition in the United States, smaller even than the Liberal United Church of Christ. In these circumstances, percentage increases can seem dramatic when the baseline is small."«

Imagine an Orthodox parish with 50 members growing to 100. That's a doubling, a 100-to-30-ton increase! It's spectacular on a local level. But it doesn't change the national religious landscape. It's like adding a drop of water to the ocean and saying, "Look, the level is rising!"«

What really attracts converts

Let's talk about what's happening in these growing Orthodox parishes. The testimonies are fascinating and reveal something important about our times.

Ben Christenson, 25, grew up in the Anglican Church. He says, «The hardest thing about growing up in my church is that even during my lifetime, there have been so many changes. I’ve realized there really is no way to stop change.» He’s seen the choir in robes replaced by a «worship group,» and long-standing positions on issues LGBT As things evolve, Pride and Black Lives Matter flags appear in front of the church doors. For him, Orthodoxy offers stability: 2000 years of history, unchanged traditions.

Emmanuel Castillo, 32, a former wrestler who started at read the Bible While guarding Al-Qaeda prisoners at Guantanamo Bay, he found his Protestant church too reminiscent of his Saturday nights at a bar: "The same kind of lighting, the same kind of music, "The same kind of feeling, and after reading the Gospels and the Book of Acts, I knew that this wasn't how they worshipped 2000 years ago."»

The men interviewed spoke of seeking something "masculine"—two-hour (or longer) liturgies, extreme fasting, regular confessions, prescribed prayers. Father Josiah Trenham, an Orthodox priest, spoke of the "feminization" of the Christianity western, where most of the worshippers are women and where services are dominated by emotional songs, people swaying, hands raised, eyes closed in ecstasy.

But here's the thing: it's not just Orthodoxy that's attracting them. Young men are also turning to traditional Latin Masses in Catholicism, and to the more conservative forms of Anglicanism and Lutheranism. It's a movement toward traditionalism in general, not specifically toward Orthodoxy.

The role of the internet and the pandemic

A crucial factor: many of these conversions were facilitated by YouTube and podcasts. Father Truebenbach, of an Orthodox church in Salt Lake City, says that most of the new converts discovered Orthodoxy online during the pandemic lockdowns.

It's ironic when you think about it: it's a hyper-connected, consumerist culture that makes these stories of conversion to an "unchanging" tradition possible. Without the internet, Matthew Ryan, a 41-year-old former atheist, would never have seen the YouTube commentary on good and evil that launched him on his spiritual quest.

Before the internet, if you lived in a small Midwestern town, you probably never met an Orthodox Christian in your life. Now, you can stream a complete Orthodox Divine Liturgy, listen to patristic theology podcasts, and connect with converts from around the world.

Other signs of religious vitality

Orthodoxy is not the only sign of vitality. There are other interesting movements, even if they do not (yet) translate into massive statistical changes.

Religious groups with high fertility rates – such as the Mormons, Christians Conservative evangelicals and some traditionalist Catholic communities maintain their membership numbers better than mainstream denominations. Black Americans remain the most religious demographic group, with 73% identifying as Christian (compared to 62% in the general population).

Movements such as that of "tradwives" (women who adopt traditional domestic roles) or the growing interest in home schools in some religious circles show that there are pockets of renewal, even if they are difficult to quantify.

Why the media love to talk about wake-up calls

Journalists love conversion stories. It's human nature. A story of a young man who abandons atheism to fast for 40 days and attend five-hour liturgies is infinitely more captivating than a graph showing a horizontal line over five years.

The media also tend to generalize from local examples. An Orthodox church tripling in size in Salt Lake City becomes "a tsunami of conversions across America." A priest who says he sees many young men in his parish becomes "young American men are turning to Orthodoxy en masse.".

It's not necessarily bad faith. It's just that anecdotes are easier to tell than complex statistical trends. And frankly, they're more interesting to read.

Understanding what is really at stake

The difference between local and national trends

Here's something crucial to understand: the two realities can coexist. Orthodox parishes can explode in size in certain cities, while at the national level, Orthodoxy remains stable or tiny.

Imagine America as a giant 330-million-piece puzzle. Some pieces shift dramatically—here an Orthodox community doubles in size, there an evangelical megachurch loses half its members, elsewhere a community of nuns forms in a college town. But when you step back and look at the big picture, it all balances out. The overall puzzle doesn't change much.

That's exactly what the Pew data shows. There is movement. About 35% of American adults have changed religion since childhood. That's huge! But these changes largely cancel each other out at the national level.

The "calm before the storm" effect«

Ryan Burge, a professor at Washington University in St. Louis and an expert on the American religious landscape, offers an intriguing interpretation. According to him, this stability since 2020 could be "the calm before the storm.".

He refers to a historical precedent: between the late 1980s and early 1990s, the percentage of Americans who identified as Christian fell from 90% to about 80%, then remained stable for more than a decade before falling again.

In other words, religious declines don't always occur in a linear fashion. Sometimes they stabilize for a while before resuming. Burge suggests we might be experiencing one of these pauses before the decline resumes.

Why this pause now? Several hypotheses are circulating. The pandemic may have temporarily changed religious behaviors. Those who remained religious in 2020 may be the ones who will remain so no matter what—a resilient «core group.» Or perhaps recent cultural and political shocks have temporarily solidified religious identities.

But Burge and other researchers believe that, in the long term, the decline will likely resume. Why? Because of demographics.

The demographic time bomb

Here is the most important factor for the future of religion in America: the generations replacing the old ones are much less religious.

Americans over 71 are religious at a rate of 83%. When this generation passes away (in the next 10-20 years), it will be replaced by the current generation of young adults, who are only 55% religious.

It's simple math. Even if no one changes their mind, even if the rates remain perfectly stable in every age group, the religious makeup of America will inevitably change. The religious age and the death of the elderly, and the non-religious age and the replacements.

Think of it like a building where the apartments on the upper floors are occupied by believers and those on the lower floors by non-believers. The people on the upper floors age and gradually leave the building, while new tenants—mostly non-believers—move in on the ground floor. Even if no one changes floors, the overall composition of the building will change.

Unless—and this is the big "unless"—something fundamentally changes. Unless younger generations suddenly become more religious as they get older, which would be a major historical reversal. Or unless there is a massive wave of conversions, far larger than what we are currently seeing.

What young people are really looking for

Let's listen carefully to what young people who are turning to traditional forms of religion are saying. They're not talking about looking for an "easier" or more "comfortable" religion. On the contrary.

Ben Christenson talks about looking for something that has "weight." Emmanuel Castillo talks about wanting to be "pushed physically and mentally." These men actively seek out difficulty, challenge, and demandingness.

In a society where you can customize your coffee in 47 different ways, where Netflix asks you anxiously "Are you still watching?" after three episodes, where everything is designed to be easy and frictionless, some young people are looking for exactly the opposite.

They want five-hour liturgies. They want to fast for 40 days. They want regular confessions, prescribed prayers, strict rules. Why? Perhaps because effort gives meaning. Perhaps because in a world of infinite choices, clear boundaries are reassuring. Or perhaps simply because they grew up in such a comfortable world that they crave something that truly challenges them.

But here's the crucial point: even if this search is real and profound for those who experience it, it only concerns a minority. Most young people aren't looking for five-hour liturgies. They're looking to sleep in on Sunday morning after a Saturday night out.

The importance (and limitations) of online theological debate

One final, fascinating element: many of these conversions involve a phase of intense online intellectual exploration. Young men read Jordan Peterson, then discover the Church Fathers. They watch theological debates on YouTube. They participate in discussions on Reddit or other forums.

The internet has democratized access to high-level theology. You can now read Saint Augustine, Listen to the teachings of Saint John Chrysostom or Saint Thomas Aquinas online for free. You can hear priests and theologians explain complex concepts. You can watch Orthodox liturgies, Latin Masses, and traditional Anglican services without ever leaving your couch.

But there's a paradox. These online communities can also become echo chambers. Someone who watches a video about Orthodoxy will see YouTube recommend ten other videos about Orthodoxy. The algorithms don't necessarily show a balanced view. They show what keeps people engaged.

Furthermore, online theology can become very abstract, very intellectualized. It's one thing to debate the procession of the Holy Spirit in YouTube comments, it's quite another to live one's faith concretely on a daily basis with all its contradictions and difficulties.

So, is there an awakening or not?

The honest answer: it depends on what you mean by "wake-up call" and where you look.

If by "revival" you mean a massive reversal of national trends, a mass return of young people to religion, an increase in the percentage of religious Americans – then no, there is no revival. The numbers are clear on that.

If by "revival" you mean pockets of renewed religious energy, growing communities in certain places, an increased interest in traditional forms of faith among a minority of young people – then yes, something is happening. It's not a complete myth.

But be careful not to confuse these two things. Hundreds of young men discovering Orthodoxy is significant for these men and for these parishes. It's a real life transformation. But it's not a major sociological shift in a country of 330 million inhabitants.

What the future might hold

No one can predict the future with certainty, but we can identify some possible scenarios.

Scenario 1: Continued stability. The numbers remain roughly where they are now. America will become neither more nor less religious for a few more years, perhaps even a decade. Local movements continue, but balance each other out at the national level.

Scenario 2: The decline resumes. After this five-year pause, the downward trend resumes, driven by demographic replacement. In 20 years, religious Americans could be a minority for the first time in the country's history.

Scenario 3: A real awakening. Contrary to statistical expectations, conversions are becoming numerous enough to change national trends. Young people are becoming more religious as they get older, rather than less so. This is the least likely scenario according to current data, but not impossible.

Scenario 4: Polarization. Religious America is divided into two distinct camps: on one side, a minority of highly committed and traditionalist believers; on the other, a majority of non-religious or "cultural believers" who are not very devout. The middle ground is disappearing.

The most likely scenario? Probably a mix of scenarios 2 and 4. A general decline with increasing polarization.

Lessons to be learned

What can we learn from all this?

First lesson: Beware of anecdotes. Personal stories are powerful and important, but they don't replace data. A parish doubling in size makes for a good story, but doesn't necessarily represent a national trend.

Second lesson: Religious change is slow. Major transformations in the religious landscape take generations, not years. What we see today is the result of trends that began 40 or 50 years ago. And what we do today will only be fully seen in 40 or 50 years.

Third lesson: Demography is destiny. We can philosophize about theology, debate on social media, write thousands of articles. But in the end, what will matter most is who has children and how they raise them. Today's less religious generations will become tomorrow's adults.

Fourth lesson: Human needs do not change. Whether in Orthodoxy, traditional Catholicism, or other demanding forms of faith, young people who convert are searching for something profound: meaning, community, challenges, structure. These needs are real and enduring, even if the ways of satisfying them evolve.

Fifth lesson: The future is not written. Current trends are not physical laws. Societies can change direction. A major spiritual awakening remains theoretically possible, even if nothing in the current data suggests it. History teaches us that surprises do happen.

Look beyond the headlines

So, is there really a religious revival in the United States? If you read the headlines, you might believe it. If you visit some Orthodox churches or Latin Masses, you might see it with your own eyes. But if you look closely at the national data, the answer is clear: no, there is no measurable revival at the national level.

This doesn't mean that nothing is happening. Individual stories of spiritual transformation are real and important. Growing communities do exist. An increased interest in traditional forms of faith is observable in some circles.

But a revival, in the historical sense of the term—like the Great Awakening of the 18th century or the Evangelical Revival of the 19th century—is characterized by massive and measurable changes that affect all of society. That is not what we are seeing today.

What we are experiencing is more subtle: a stabilization after decades of decline, with pockets of religious vitality in an ocean of ongoing secularization. It's less spectacular than a revival, but perhaps more interesting to study. Because it tells us something about our times: in an increasingly secularized society, some are seeking precisely the opposite. And that is fascinating.

Time will tell if this stability is temporary—a mere respite in a long decline—or the beginning of something new. For now, the only certainty is that reality is more complex than the headlines suggest. It always is.