Reading from the Book of Genesis (2:7-9; 3:1-7a)

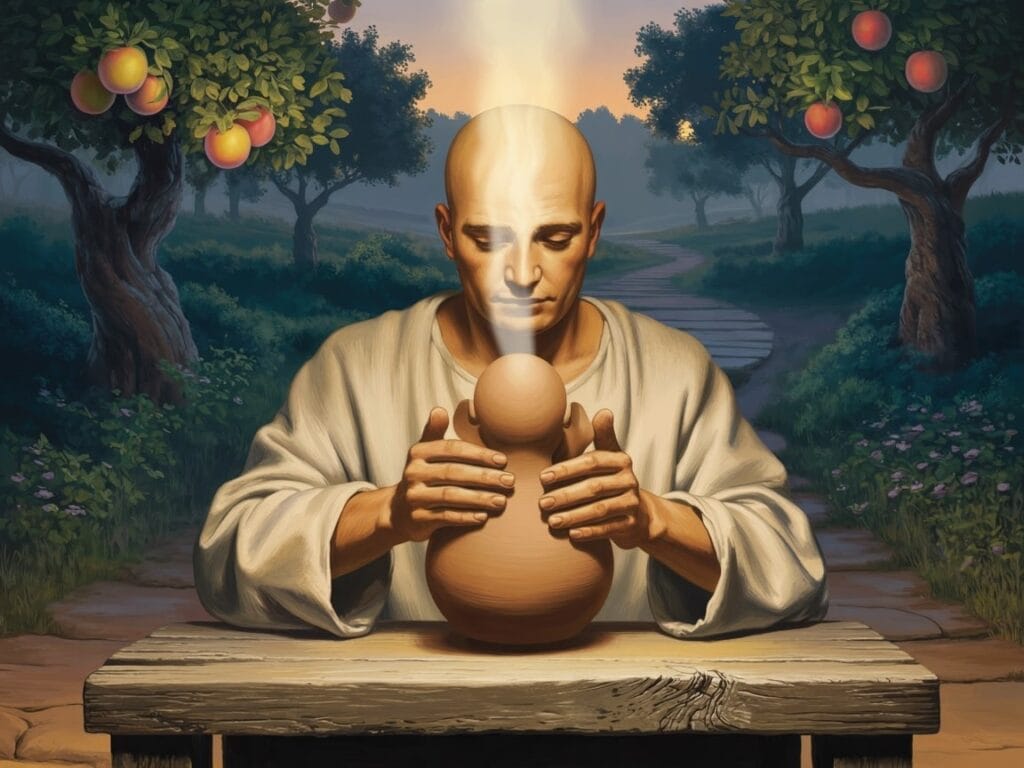

The Lord God formed man of dust from the ground and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, and man became a living being. The Lord God planted a garden in Eden, in the east, and there he placed the man whom he had formed. And out of the ground the Lord God made every tree grow, both desirable and savory. In the midst of the garden was the tree of life, and the tree of the knowledge of good and evil.

Now the serpent was more cunning than any other wild animal that the Lord God had made. He said to the woman, “Did God really say to you, ‘You may not eat from any tree in the garden’?” The woman said to the serpent, “We may eat from the trees in the garden. But of the fruit of the tree in the middle of the garden, God has said, ‘You may not eat from it, nor may you touch it, or you may die.’” The serpent said to the woman, “Not at all! You will not surely die! For God knows that in the day you eat from it, your eyes will be opened, and you will be like gods, knowing good and evil.” The woman saw that the fruit of the tree must have been delicious, pleasing to the eyes, and desirable because it gave understanding. So she took some of its fruit and ate it. She also gave some to her husband, and he ate it. Then the eyes of both of them were opened and they realized that they were naked.

When Dust Meets Divine Breath: Rediscovering Our Dignity in Genesis 2:7

A founding text which reveals our dual origin and invites us to fully live our human and spiritual vocation.

“The Lord God formed man of dust from the ground and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, and man became a living being.” This verse from Genesis 2:7 is one of the most famous and least understood passages in all of Scripture. In a few words of disconcerting simplicity, it reveals the mystery of our existence: we are both earth and sky, matter and spirit, fragility and grandeur. This text is addressed to every seeker of meaning who questions their deepest identity, to every believer who wishes to understand their vocation, to every human being who aspires to reconcile their body and soul in a unified and authentic life.

This article invites you on a five-step journey: we will first situate this text in its biblical and liturgical context; we will then analyze the central paradox of our dual nature; we will explore three essential dimensions (creature humility, spiritual dignity, and relational vocation); we will discover the resonances of this passage in the patristic tradition and spirituality; finally, we will propose concrete ways to embody this message in our daily lives.

Context

Genesis 2:7 belongs to the second creation narrative, distinct from the first chapter of Genesis in its style, vocabulary, and theological approach. While Genesis 1 presents an orderly seven-day creation, quasi-liturgical in its structure, Genesis 2 adopts a more intimate, human-centered narrative that uses anthropomorphic language to describe divine action. This second narrative, often attributed to the Yahwist tradition, does not seek to contradict the first but to complement it with a more existential and relational perspective.

In the immediate context, this verse occurs before the creation of the Garden of Eden and before the formation of woman. It describes the foundational moment when humanity receives its special existence, distinct from the rest of creation. The Hebrew text uses terms rich in meaning: " Adam » for man, derived from « adamah » (the earth), and « nishmat chayyim » (breath/breath of life), which evokes the vital and spiritual dimension.

Liturgically, this passage is proclaimed notably on Ash Wednesday, the first day of Lent, reminding the faithful of their mortal condition: "You are dust and to dust you shall return." This liturgical use underlines the penitential dimension and the reminder of our humble origins, but also, paradoxically, of our incomparable dignity since we carry within us the very breath of God. The text also resonates during funerals and celebrations that invite us to meditate on the mystery of human life.

The full excerpt from Genesis 2:7-9 places the creation of man within a larger project: “Then the Lord God formed man of dust from the ground and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, and man became a living being. The Lord God planted a garden in Eden, in the east, and there he placed the man whom he had formed. And out of the ground the Lord God made every tree grow, desirable in appearance and with delicious fruit.” This sequence reveals that man is not created in the abstract but for a specific purpose: to inhabit the garden, to cultivate it, to enter into a relationship with God and with creation.

The significance of this verse goes far beyond the historical or scientific. It is not a technical account of our biological origins, but a theological affirmation of our profound identity. As we read this passage, we are invited to realize that our existence is neither a cosmic accident nor a simple natural emergence: it results from a deliberate, personal, and intimate act of God who shapes us and animates us with his own breath.

Analysis: The paradox of dual nature

At the heart of Genesis 2:7 lies a striking paradox that defines human existence: we are simultaneously dust and breath, matter and spirit, earth and sky. This tension is not a contradiction to be resolved but a reality to be inhabited, a vocation to be fully embraced. Analyzing this paradox reveals the profound dynamics of our human condition.

On the one hand, the text unambiguously affirms our humble material origin: God "formed man from dust taken from the ground." The verb "to mold" (yatsar in Hebrew) evokes the work of the potter who shapes the clay with his hands. This image underlines our proximity to material creation: we are made of the same substance as the earth, the same “soil” from which plants and animals come. There is nothing glorious, nothing eternal in this dust; it expresses our radical fragility, our vulnerability, our mortal condition. “You are dust and to dust you will return”: this divine sentence after the fall only confirms what we are from the beginning.

But the story doesn't end there. Immediately after shaping this body of earth, God performed an extraordinary gesture: "He breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, and man became a living being." This divine breath (nishmat chayyim) is not simply a biological principle that would activate an inert mechanism. The Fathers of the Church and the Jewish tradition recognized in this breath the very Spirit of God, his personal presence that comes to inhabit man and constitute him as a "living being" in the full sense. Man does not become alive by a simple biological animation; he becomes alive because he receives within himself something of divine life itself.

This dual constitution creates a dynamic tension that defines our existence. We are neither pure spirits nor mere animals. Unlike angels, we have bodies, we are incarnate, rooted in matter, and subject to the laws of nature. Unlike animals, we carry within us a spiritual dimension, a capacity for transcendence, an openness to infinity. Hebrew biblical anthropology expresses this complexity through several terms: nephesh (the vital soul, common to animals), ruah (the spirit, the emotional and moral breath), and neshama (the intellectual and spiritual soul, properly human).

The biblical text thus affirms that man is a "living being" (nephesh hayah). This expression, sometimes translated as "living soul," does not designate an immortal soul separated from the body, but rather the living unity of matter animated by the divine breath. Man does not have a body; he is a body animated by the Spirit. He does not have a soul; he is an incarnate soul. This holistic vision opposes dualisms that scorn the body in favor of the soul or that reduce man to his material dimension alone.

The existential scope of this dual nature is immense. It reminds us that we cannot fulfill ourselves by denying our carnal condition (through a disembodied spiritualism), nor by ignoring our spiritual vocation (through a reductive materialism). We are called to live in the unity of our being, honoring both our body and our spirit, our earthly roots and our celestial openness. This creative tension constitutes the very place of our freedom and our responsibility: between the dust that calls us to humility and the divine breath that calls us to greatness, we must choose, at every moment, the path of our authentic humanization.

Creature humility: accepting our fragility

The first dimension of the message of Genesis 2:7 concerns our condition as creatures, our fundamental humility before the Creator. The reminder of our dusty origins is not a condemnation but an invitation to lucidity and gratitude.

The image of dust (aphar in Hebrew) runs throughout Scripture as a powerful symbol of human humility and finitude. Why does God choose dust, and not a nobler material, to fashion man? This question has intrigued commentators of all centuries. The answer lies in divine pedagogy: by creating us from dust, God teaches us from the beginning that we are nothing in ourselves, that our existence is a free gift, that we depend entirely on his creative will.

This humble origin protects us from two symmetrical and equally dangerous temptations. First, the temptation of pride and self-sufficiency: how could we be proud, we who came from dust and will return to it? Second, the temptation of despair and self-contempt: if we are made of dust, it is precisely because God wanted to create us that way, and this dust becomes noble by the very fact that He chooses it and shapes it with His hands.

Accepting our creaturely fragility opens a path to spiritual freedom. Recognizing that we are dust means abandoning the illusions of omnipotence that chain us to anxiety and competition. It means accepting our physical, intellectual, and moral limitations, without sinking into resignation. It means understanding that our worth does not depend on our performance, our power, or our perfection, but on the loving gaze of the One who fashioned us.

This creaturely humility has concrete implications for our relationship with creation. Fashioned from the same soil as plants and animals, we share with them a common earthly origin. Far from authorizing us to arrogantly dominate nature, this kinship calls us to responsible management, ecological solidarity, and a profound respect for all that lives. We are not the despotic owners of creation but its guardians, called to "work and guard" the garden entrusted to us.

Moreover, awareness of our common fragility creates a universal brotherhood among all humans. Regardless of our ethnic origin, social status, education, or talents, we all share the same condition of dust animated by the divine breath. This ontological equality establishes a solidarity that transcends all artificial divisions: before God, we are all equally creatures, equally fragile, equally loved. To recognize the humble origin of the other is to recognize them as brothers, as participants in the same vulnerable and precious humanity.

Finally, creaturely humility prepares us to welcome divine grace. Saint Augustine expressed it beautifully: God created man from nothing (dust) to demonstrate that everything in him is a free gift. We cannot boast of anything, for everything comes to us from Him. This truth frees us from the burden of self-justification and opens the space for joyful gratitude. To accept being dust is to accept being filled with a love that does not depend on our merits.

Spiritual dignity: honoring the divine breath

If dust recalls our humility, the divine breath reveals our incomparable dignity. Genesis 2:7 does not stop at our earthly origin; it culminates in the breathing that makes us living beings animated by God himself.

The gesture of God breathing his breath into the nostrils of man is overwhelmingly intimate. It evokes a closeness, a tenderness, a gift of self that surpasses anything we could imagine. God does not create man from a distance, with a simple word as with the stars or plants; He shapes him with his hands and directly communicates his own breath of life to him. This personal communication establishes a unique relationship between the Creator and his human creature.

The “breath of life” (nishmat chayyim) is not a simple biological vital principle but a participation in divine life itself. The Jewish and Christian tradition has identified this breath with the Spirit of God (ruah Elohim), present from the first verse of Genesis, hovering over the waters of original chaos. By breathing his Spirit into man, God communicates to him something of his own nature: intelligence, freedom, the capacity to love, moral conscience, openness to transcendence. Man thus becomes capax Dei, “capable of God,” able to know and love Him.

This spiritual dignity is manifested first in our capacity for knowledge and reason. Unlike animals that react by instinct, man can reflect, abstract, contemplate the truth, and seek the meaning of things. In the Hebrew tradition, the neshama refers precisely to this intellectual soul, the seat of intuition and reason, which connects each human being to the divine source. This intellectual capacity makes us responsible for our actions, capable of moral discernment, called to choose freely between good and evil.

The divine breath also gives us a capacity to love that reflects the very love of God. Man is not only a thinking being (homo sapiens) but a loving being, created for relationship, for self-giving, for communion. The personalist tradition of the 20th century, embodied in particular by Pope John Paul II, emphasized that man is "the only creature on earth that God wanted for itself," that is, for the relationship of love. This vocation to love is rooted in the divine breath that animates us and pushes us towards the other.

Our spiritual dignity also implies a vocation to freedom. Created in the image of a free God, man is called to exercise his freedom responsibly. This freedom is not arbitrary or capricious; it is naturally oriented toward the good, the true, the beautiful, because it participates in the divine breath which is itself Truth, Goodness, and Beauty. The Augustinian tradition speaks of this freedom as a “freedom for” (the good) rather than a simple “freedom to” (to choose indifferently).

Honoring the divine breath within us therefore means taking our intellectual, moral, and spiritual vocation seriously. It means cultivating our intelligence through study and contemplation, refining our moral conscience through examination and discernment, and nourishing our spiritual life through prayer and the sacraments. It means rejecting everything that degrades our humanity: willful ignorance, moral mediocrity, enslavement to the passions, and confinement within the material horizon.

This spiritual dignity also underpins fundamental human rights. If every human being carries within them the breath of God, then each one possesses an inalienable value, independent of their social usefulness, abilities, or performance. From the weakest to the strongest, from the newborn to the elderly, from the sick to the healthy, all share the same ontological dignity that commands respect and protection. Any social, economic, or political system that violates this fundamental dignity opposes God's creative design.

The relational vocation: becoming fully alive

The third essential dimension of Genesis 2:7 concerns the relational vocation of man. The text affirms that, through divine inspiration, "man became a living being" (nephesh hayah). This expression does not only designate biological existence but a quality of life that flourishes in relationship with God, with others and with creation.

To be fully alive, in the biblical sense, means first of all to be in relationship with God. The divine breath that animates us is not an impersonal principle but a personal presence that calls for communion. God does not create man to exist autonomously and in isolation, but to enter into a dialogue of love with Him. The immediate aftermath of the Genesis 2 story confirms this: God places man in the garden, speaks to him, gives him commandments, and walks with him in the cool of the evening. This original intimacy reveals our profound vocation: we are created to know God and be known by Him, to love Him and be loved by Him.

The patristic tradition has developed this relational vision in magnificent ways. Saint Irenaeus of Lyons, in the 2nd century, speaks of man as one called to an ever deeper communion with God, in a process of spiritual maturation that he calls "recapitulation." For Irenaeus, the first Adam (the one of Genesis 2) prefigures the second Adam, Christ, who comes to restore and fulfill humanity's relational vocation by perfectly uniting human and divine natures. Man becomes fully alive only by being united to the incarnate Word.

This relational vocation also extends to other human beings. The story of Genesis 2 continues with the creation of woman, emphasizing that "it is not good for the man to be alone." Human beings are fundamentally social, created for community, for sharing, for mutual love. The divine breath that animates us naturally pushes us toward others, because it makes us participants in Trinitarian love, which is a communion of persons. John Paul II insisted on this "spousal" dimension of human existence: we are created for reciprocal self-giving, to become ourselves by giving ourselves to others.

The relational vocation also implies a responsibility toward creation. The biblical text specifies that God places man in the garden "to work it and keep it." This dual mission reveals that our relationship with the created world is neither one of exploitation nor contempt, but of cultivation and preservation. Fashioned from the same soil as plants and animals, we are called to a harmonious relationship with them, respecting their integrity while making them bear fruit for the common good.

To become fully alive, then, is to inhabit these three relational dimensions in their unity. It is to live in constant dialogue with God through prayer and the sacraments; it is to build authentic relationships with others, based on respect, justice, and love; it is to exercise our ecological responsibility with wisdom and moderation. Every time we neglect one of these dimensions, we become impoverished, we move away from our vocation, we become less alive.

Christian spirituality has always recognized that the abundant life promised by Christ (John 10:10) is rooted in this harmonious threefold relationship. We cannot fulfill ourselves by withdrawing into ourselves, fleeing the world, or ignoring God. On the contrary, it is by opening ourselves to God, to others, and to creation that we discover our true identity and fully become the "living beings" that God intended us to become from the beginning.

Tradition

The passage from Genesis 2:7 has profoundly influenced Christian tradition and spirituality throughout the centuries. Church Fathers, medieval theologians, and modern mystics have drawn from it an inexhaustible source of reflection on the mystery of man.

Saint Augustine of Hippo (354-430), one of the four great Latin Fathers of the Church, developed an anthropology deeply influenced by Genesis 2:7. For Augustine, divine inspiration creates in man a unique capacity to turn to God and find rest for his heart in Him alone. His famous Confessions opens with this intuition: "You made us for Yourself, Lord, and our heart is restless until it remains in You." This sacred restlessness, this quest for God inscribed in the heart of man, comes precisely from the divine breath that animates us and naturally directs us towards our Source.

Saint Irenaeus of Lyons (c. 130-200), a witness to the Apostolic Tradition, meditated on Genesis 2:7 in his fight against Gnosticism. Against the heretics who despised the body and matter, Irenaeus affirmed the goodness of material creation and the dignity of the human body fashioned by the hands of God. For him, the breath of life communicated to Adam prefigures the gift of the Holy Spirit who, in Christ, comes to restore and fulfill fallen humanity. The "recapitulation" brought about by the second Adam (Christ) consists precisely in renewing in us this original union of matter and spirit, of the earthly and the heavenly.

The Catholic liturgy has significantly integrated Genesis 2:7, particularly in celebrations that mark key moments in human existence. On Ash Wednesday, the Church proclaims this text to remind the faithful of their mortal condition and call them to conversion. The rite of the imposition of ashes, accompanied by the formula "Remember that you are dust and to dust you shall return," establishes a direct link with our passage. But this memory of our fragility is never separated from the memory of our dignity: we are dust, certainly, but dust animated by the breath of God, called to rise again in Christ.

The spiritual tradition has also meditated on the symbolism of breath (ruah, pneuma) as the presence of the Holy Spirit. The breathing exercises practiced by certain monastic traditions are inspired by this intuition: to breathe consciously is to remember that each breath is a gift from God, a participation in his Spirit. Hesychastic prayer, in the Eastern tradition, intimately associates the repetition of the name of Jesus with the rhythm of breathing, thus creating an "incessant" prayer that unites body and spirit.

Contemporary theologians have updated the message of Genesis 2:7 in dialogue with modern science. Creation theology does not conflict with the theory of biological evolution, because the two discourses operate at different levels: science describes the material mechanisms of human emergence, while faith reveals the theological meaning of this emergence. Whether man comes from a long evolutionary process or from immediate molding matters less than the fundamental truth affirmed by the text: humanity is willed by God, created in his image, animated by his Spirit, and called to communion with him.

The Second Vatican Council, in the constitution Gaudium et Spes, reaffirmed this integral vision of man as "unity of body and soul," created in the image of God and called to a transcendent vocation. Conciliar anthropology is directly rooted in Genesis 2:7, rejecting any dualism that would separate or oppose body and spirit. Man is a unified whole, where the body is animated by the soul which itself is vivified by the Spirit.

Finally, contemporary spirituality is rediscovering the importance of incarnation and ecology in the light of Genesis 2:7. The encyclical Laudato Si' Pope Francis's message invites us to recognize our common origin with all creation and to exercise our responsibility as guardians of the earthly garden. The reminder that we are fashioned "from the dust of the ground" prohibits us from any anthropocentric arrogance and calls us to humble solidarity with all creatures.

Meditations

How can we concretely embody the message of Genesis 2:7 in our daily lives? Here are seven practical steps to integrate this biblical wisdom into our spiritual and existential journey.

1. Morning Gratitude Practice : Every morning, upon waking, take a few moments to breathe consciously and thank God for the gift of life. Before rising, place your hand on your heart and say to yourself, “Thank you, Lord, for this breath of life you have given me today.” This simple practice anchors your day in the recognition of your condition as a beloved creature.

2. Meditation on the dual nature Once a week, meditate for fifteen minutes on the paradox of your identity: dust and breath, humble and worthy, limited and called to infinity. Read Genesis 2:7 slowly, then sit in silence and contemplate this truth about yourself. Let this meditation transform your view of yourself and others.

3. Examination of creaturely conscience : During your daily self-examination, add two specific questions inspired by Genesis 2:7. First: “Today, have I lived in humility, recognizing my condition as a creature dependent on God?” Second: “Today, have I honored the divine breath within me, cultivating my intellectual, moral, and spiritual life?” This twofold question will help you discern when you have lived in accordance with your vocation, and when you have strayed from it.

4. Bodily practice of incarnation Since your body is fashioned by God and animated by His Spirit, treat it with respect and gratitude. Adopt a healthy lifestyle (balanced diet, physical exercise, adequate sleep) not out of vanity but out of respect for the divine creation that you are. Reject speeches that despise the body or, conversely, idolize it. Seek the harmonious unity of your bodily and spiritual being.

5. Relational commitment : Identify someone in your life whom you tend to neglect or despise. Remember that they too are “dust animated by the divine breath,” that they carry within them the same inalienable dignity as you. Make a concrete gesture of attention, respect, or service toward this person, in recognition of their intrinsic worth. Let Genesis 2:7 transform your relationships by making you aware of the presence of the divine breath in every human being.

6. Ecological responsibility : Choose a concrete ecological gesture that you can integrate into your daily life (waste reduction, energy saving, responsible consumption). Do it not out of political ideology but out of loyalty to your vocation as guardian of the earth's garden. Remember that you are shaped from the same soil as the earth you tread, and that this kinship commits you to a benevolent responsibility.

7. Breath Prayer : Adopt a form of prayer that combines breathing and invocation. For example, as you inhale, pray inwardly: "Lord God"; as you exhale: "breath of life in me." Practice this prayer for a few minutes each day, while traveling, walking, or before falling asleep. It will help you realize that breathing is a spiritual act, a continual communion with the God who animates you.

The transforming force of the divine breath

Genesis 2:7 is not a mere account of origins, an archaeological curiosity of an ancient text. It is a living word that continues to reveal to us our deepest identity and our highest calling. By reminding us that we are dust animated by the breath of God, this verse reconciles the apparent contradictions of our existence and opens up a path to authentic humanization.

The transformative power of this passage lies precisely in its creative paradox. Accepting that we are dust frees us from pride and performance anxiety; recognizing the divine breath within us elevates us to an inalienable dignity that establishes our rights and responsibilities. This dual consciousness creates a dynamic balance that preserves us from both self-contempt and arrogance, from despair and presumption.

In a world marked by fragmentation, alienation, and loss of meaning, the message of Genesis 2:7 resonates with particular urgency. It reminds us that we are neither biological machines devoid of purpose nor disembodied spirits floating above the world. We are embodied and spiritual beings, rooted in the earth and open to the sky, called to a fully human life that integrates body and spirit, matter and transcendence.

The final invitation of this text is revolutionary: it calls us to a profound conversion of our view of ourselves, of others, and of creation. Seeing each human being as "dust animated by the divine breath" radically transforms our social relationships, our political commitments, and our ethical choices. This establishes a universal brotherhood that transcends all artificial divisions of race, class, culture, or religion. It also imposes an ecological responsibility that flows naturally from our common origin with all creation.

Fully becoming the “living beings” that God wanted us to become therefore involves a demanding spiritual journey: cultivating our creaturely humility without falling into self-contempt; honoring our spiritual dignity without sinking into pride; living our relational vocation in all its dimensions (with God, with others, with creation). It is only by fully inhabiting this creative tension between dust and breath, between the humble and the sublime, that we will discover our true freedom and our true joy.

May Genesis 2:7 become for you not only an object of intellectual contemplation, but an active word that shapes your daily existence. May you be able, day after day, to welcome with gratitude the divine breath that animates you, to accept with serenity your condition of dust, and to live with generosity your vocation as a living being created for communion. For it is by fully assuming this paradoxical identity that you will truly become yourself, in the image of the One who fashioned you with his hands and breathed into you his Spirit.

Practical

- Breathe consciously : Every morning, take three deep breaths, aware that each breath is a renewed divine gift, a participation in the creative Spirit.

- Meditate weekly : Spend fifteen minutes a week reading lectio divina from Genesis 2:7, letting the Word penetrate your heart and transform your outlook.

- Practice humility : In your successes, remember that you are dust; in your failures, remember that you carry the divine breath.

- Honor your body : Adopt a lifestyle that respects the unity of your bodily and spiritual being, rejecting any disembodied dualism or reductive materialism.

- Recognize the dignity of others : Every day, take a contemplative look at at least one person, recognizing in them the presence of the divine breath which establishes their inalienable dignity.

- Assume your ecological responsibility : Integrate a concrete gesture of safeguarding creation into your daily life, in fidelity to your vocation as guardian of the earthly garden.

- Pray with your breath : Unite invocation and breathing in a simple and rhythmic prayer which anchors your existence in the continual presence of the God who animates you.

References

- Biblical text : Book of Genesis, chapter 2, verse 7. Translations consulted: Jerusalem Bible, Official Liturgical Translation, Segond 21 Bible, Bible du Semeur.

- Biblical commentaries : Annotated Bible, Exegetical Commentaries on Genesis 1-2, Studies on the Two Creation Accounts and Their Respective Traditions.

- Fathers of the Church : Saint Augustine of Hippo (Confessions, The City of God), Saint Irenaeus of Lyon (Against heresies, Demonstration of apostolic preaching), Latin and Greek patristic tradition.

- Hebrew Biblical Anthropology : Studies on the concepts of nephesh, ruah, neshama in the Jewish and Christian tradition, Hebrew Kabbalah and its levels of the soul.

- Catholic Magisterium : Vatican Council II (Gaudium et Spes), John Paul II (theology of the body, adequate anthropology), International Theological Commission on the human person created in the image of God.

- Contemporary Theology : Christian anthropology according to the Catholic and Orthodox traditions, theology of creation in dialogue with the sciences, integral ecology (Laudato Si').

- Liturgical Resources : Catholic liturgical lectionary, use of Genesis 2:7 in the liturgy of Ash Wednesday and celebrations of human life.

- Practical spirituality : Conscious breathing exercises and hesychastic prayer, practices of bodily and spiritual incarnation, moral discernment and examination of conscience.