A reading from the book of the prophet Isaiah

On that day, the Lord Almighty will offer all peoples a banquet of choice dishes and exquisite wines on his mountain, a feast of delectable food and pure wines. On this mountain, he will remove the veil of mourning that surrounds all peoples and the shroud of all nations. He will swallow up death forever. The Lord God will wipe away the tears from all faces, and he will remove the disgrace of his people from all the earth. The Lord has spoken.

And on that day it will be proclaimed: «Here is our God, in whom we have placed our trust, and he has delivered us; this is the Lord, in whom we have placed our hope; let us rejoice and be glad: he has saved us!» For the hand of the Lord will remain on this mountain.

When God turns our tears into a feast: the promise that changes everything

How an exiled prophet reveals to us the definitive face of Christian hope.

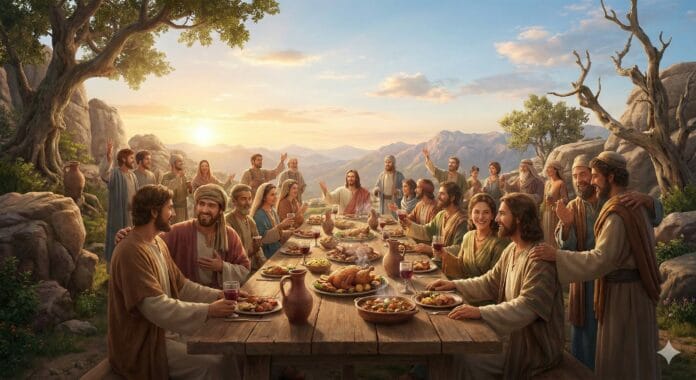

Imagine yourself at rock bottom. Everything has collapsed around you. Your life resembles a field of ruins. And in the midst of this chaos, someone extends an invitation, engraved in letters of gold, to the most extraordinary banquet ever held. A feast where death itself will be definitively vanquished, where every tear will be tenderly wiped away, where humiliation will give way to restored dignity. This is precisely what the prophet Isaiah proclaims in this dazzling passage. Far from being a mere comforting metaphor, this text reveals to us the very heart of God's plan for humanity: to radically transform our mortal condition into shared eternal life.

The genesis We will examine the historical and theological aspects of this extraordinary promise, its roots in the experience of a broken people, and how it foreshadows the work of Christ. We will then explore the threefold dimension of the divine feast: abundant food, universal communion, and victory over death. Finally, we will see how this vision concretely transforms our way of living today, facing suffering, and hoping for ultimate fulfillment.

The context of a promise born in tears

To understand the explosive power of this text, we must first transport ourselves to the world of Isaiah. We are probably in the sixth century BCE, in a period that specialists call the post-exilic or proto-apocalyptic Isaiah. The people of Israel have just experienced one of the most devastating traumas in their history: the destruction of Jerusalem by the Babylonians in 587 BCE, followed by the forced exile of the elites to Babylon.

Imagine what this represents. The Temple, the beating heart of the Jewish faith, reduced to ashes. The Davidic monarchy, the divine promise of eternal reign, annihilated. The protective walls of the holy city, crumbled. And above all, this haunting question that plagues our minds: Has God abandoned us? Was our faith an illusion? Are the Babylonian gods more powerful than the Lord of Israel?

It is in this context of collective despair, national trauma, and profound humiliation that this striking prophecy arises. Chapters 24 to 27 of Isaiah form what is called "« the Apocalypse "of Isaiah," a literary collection that effects a radical shift: from judgment to salvation, from national history to the universal horizon, from the temporal to the eschatological.

The text opens with a typically prophetic phrase: «On that day.» This expression, recurring in prophetic literature, does not simply designate any future moment. It announces the «Day of the Lord,» that decisive moment when God will intervene definitively in human history to reconfigure everything according to his justice and love. It is a qualitatively different time, when the ordinary rules of existence will be suspended and transformed.

The Lord is presented with his majestic title: «the Lord of the universe» or, more literally in Hebrew, «YHWH Sabaoth,» the Lord of hosts. This title affirms God’s absolute sovereignty over all creation, visible and invisible. Faced with the humiliation of Israel, the prophet proclaims that their God is not a defeated tribal god, but the master of the entire universe.

The location of this revelation is also significant: «his mountain.» In biblical tradition, the mountain is the quintessential place of encounter between the divine and the human. It was on Mount Sinai that Moses received the Torah. It was on Mount Zion that the Temple was built. The mountain symbolizes the proximity of God, spiritual elevation, the point of connection between heaven and earth. Here, it becomes the site of the eschatological banquet, the center from which salvation will radiate to all horizons.

What immediately strikes one in the prophetic vision is its universal character: "for all peoples." We are no longer dealing with a logic of exclusive national salvation. Isaiah radically broadens the perspective. The divine feast is not reserved for Israel, but is intended for all humanity. All peoples are invited to this common table. This universalist openness is revolutionary for the time and foreshadows the missionary orientation of the Christianity.

The feast itself is described with almost carnal exuberance: "fatty meats," "heady wines," "succulent meats," "decanted wines." It is not an ascetic or symbolic meal, but a sensual, bodily celebration that engages all the senses. The Hebrew vocabulary used evokes excellence, richness, and superior quality. God does not offer leftovers or mediocrity, but the absolute best.

This emphasis on the materiality of the banquet is fundamental. It affirms that divine salvation is not an escape from the material world, but a transfiguration of it. Physical creation, far from being scorned or abandoned, will be glorified and brought to its fulfillment. This is a profoundly embodied vision of salvation, consistent with faith in the resurrection bodies that Judaism will gradually develop.

Then comes the heart of the prophecy, its incandescent core: the removal of the "veil of mourning" and the "shroud" that envelop the people. These textile images evoke the mortal condition of humanity. Since the original fall, death has been the universal destiny, the opaque veil that obscures our existence, the shroud that awaits each of us. This veil is not only physical; it is also spiritual, symbolizing ignorance, separation from God, the inability to fully perceive divine reality.

The central statement follows, abrupt and definitive: «He will swallow up death forever.» No ambiguity, no softening. Death itself will be destroyed, engulfed, annihilated. This is the first time in the Old Testament that such a radical statement appears with this clarity. Certainly, other texts mention survival or resurrection, but here, it is death as a cosmic reality that is promised total abolition.

This promise takes on its full weight when one remembers the context. For a people who have just seen their children die by the thousands, who have lost an entire generation in the siege and deportation, who mourn their dead without being able to bury them properly, this announcement is literally unheard of. Death, this implacable reality, this universal inevitability, will be conquered by divine intervention.

The following image is profoundly moving: «The Lord God will wipe away the tears from every face.» This intimate, even maternal gesture reveals a God who is close, caring, and who individually addresses each suffering. It is not about abstract or collective consolation, but about personal attention to each pain. The Lord of the universe becomes the one who dries our tears as a mother dries the tears of her child.

Note the universality once again: «all faces,» «throughout the earth.» No tear is forgotten, no suffering overlooked. Redemption will be as vast as the human condition itself. And it also includes the erasure of «the humiliation of his people.» The Hebrew term translated as «humiliation» refers to shame, disgrace, public dishonor. Israel has been humiliated before the nations; this shame will be definitively erased.

The text concludes with a scene of collective jubilation. «On that day, it will be said…» This phrase introduces what resembles a spontaneous hymn of praise from the saved people. The insistent repetition – «in him we hoped… he saved us… he is the Lord… in him we hoped…» – conveys the wonder, the joyful disbelief at the fulfillment of the promise. Patience Hope has been rewarded, and the trust maintained against all odds has proven to be well-founded.

The final phrase, "the hand of the Lord will rest on this mountain," evokes God's protective and benevolent presence. In the Bible, the hand symbolizes power, but also care and guidance. It rests; it does not strike. It is a hand that protects, blesses, and establishes. peace.

This text from Isaiah is strategically integrated into Christian liturgy. It is often proclaimed at funerals, where it offers the bereaved a radical hope in the face of death. It also resonates during liturgical seasons that anticipate the coming of the Kingdom, such as Advent, preparing the faithful to recognize in Christ the one who fulfills this ancient promise.

The theological revolution of an impossible banquet

At the heart of this prophetic passage lies a revolutionary idea that overturns all our usual categories: God chooses the shared table as the place and means of universal redemption. Salvation does not come primarily through the violence of war, nor through crushing judgment, nor through terrifying cosmic intervention, but through a feast—that is, through the most everyday, most human, most convivial experience imaginable.

The centrality of the meal in divine revelation is not insignificant. In all cultures, sharing a meal is much more than a simple biological necessity. It is a profoundly social and symbolic act. Eating together creates bonds, establishes alliances, and demonstrates mutual acceptance. Refusing to eat with someone is a form of radical exclusion. Conversely, inviting someone to one's table is a gesture of welcome, recognition, and integration into the community.

In biblical culture, this symbolic dimension of the meal is particularly pronounced. The laws of ritual purity meticulously regulate who may eat with whom, what to eat, and how to prepare food. These rules are not simply dietary taboos, but markers of identity, boundaries that define belonging to the people of the Covenant. Transgressing these rules endangers collective identity and dissolves protective boundaries.

But the feast announced by Isaiah shatters all these barriers. «All peoples» are invited, without distinction, without any preconditions of ritual purity or ethnic affiliation. The impure and the pure, Jews and Gentiles, the circumcised and the uncircumcised, all find themselves at the same table, consuming the same food, drinking from the same cups. It is a dizzying transgression of the categories that structure the identity of Israel.

This universality is not merely a humanist openness or polite tolerance. It reveals something fundamental about the very nature of God. The God of Israel is not tribal, not possessive, not exclusive. His saving will embraces all of humanity. His "mountain" is not a closed fortress, but a summit visible from every horizon, accessible to anyone who undertakes the ascent.

This vision directly contradicts all ideologies of exclusion which, throughout the centuries, have instrumentalized religion to justify segregation, oppression, and domination. Isaiah's feast proclaims that there is no hierarchy in God's love, no definitively privileged, no predestined damned. The table is immense, the places countless, the invitation universal.

But this feast is not only universal, it is also paradoxical. How can one celebrate a banquet when death itself still lurks? How can one feast beneath the shroud? This is precisely where Isaiah's prophetic genius lies: the feast is not celebrated in spite of death, but against it, with a view to its ultimate destruction. The banquet is the weapon chosen by God to conquer death.

This divine strategy may seem strange. Faced with humanity's most formidable enemy, with this power that has ravaged and destroyed since the beginning, God does not brandish a flaming sword, nor unleash his destructive wrath, but… organizes a feast. It is as if, in a citadel besieged by the army of death, God were to order not the strengthening of defenses or the preparation of a sortie, but the setting of the table and the uncorking of the finest wines.

This apparent madness actually conceals a profound wisdom. Death steals from us precisely what the feast celebrates: shared life, communion, the enjoyment of the bounty of creation. Death isolates, separates, destroys relationships. The feast gathers, unites, creates community. By inviting humanity to a sumptuous banquet, God affirms that life is stronger than death, that communion is truer than separation, that joy The true destiny of humanity is to be shared.

Victory over death is therefore not won by a superior power crushing an inferior one. It is accomplished through the manifestation of that which death can neither reach nor destroy: selfless love, shared generosity, and communion that unites. The feast itself is the form of eternity, the anticipation of the Kingdom, the already present victory of life over death.

This paradoxical dimension illuminates an essential aspect of the Christian faith. We live in a state of "already here" and "not yet." The Kingdom has been inaugurated, the victory won, but the fulfillment remains to come. We are already feasting, but in anticipation of the final banquet. Each Eucharist is simultaneously memorial and anticipation, a reminder of the promise and a foretaste of its fulfillment.

The other revolutionary dimension of this text concerns the very nature of God it reveals. The Lord who wipes away tears is not the distant monarch enthroned in an inaccessible transcendence. He is a God who descends, who bends down, who touches, who consoles. The image is almost scandalous in its tenderness. The creator of the universe, before whom the heavenly armies tremble, who measured the oceans in the palm of his hand, this God wipes away our tears with a maternal gentleness.

This revelation of divine tenderness runs throughout Scripture, but here it reaches a peak of expression. It prepares the way for the Incarnation, that even more scandalous event where God will not merely wipe away tears, but will himself weep, suffer, and die. The God of Isaiah is already the God who radically engages with the human condition, who does not remain aloof from our suffering, but enters into it to transform it from within.

This promise to have our tears wiped away is not a promise of insensitivity or oblivion. God does not erase our painful memories as one might erase marks on a painting. He wipes away our tears, that is to say, he welcomes our sorrow, acknowledges it, gives it its full legitimacy, and only then truly consoles us. Our tears are not denied, but gathered and then dried by the very hand that created all things.

Abundant food: when God goes beyond all measure

The first aspect we must explore in this prophetic vision is the extraordinary nature of the feast itself. Isaiah does not describe an ordinary meal, nor even a royal banquet by human standards. He evokes an abundance that defies imagination, a generosity that shatters all usual norms.

«Fat meats,» «full-bodied wines,» «succulent meats,» «decanted wines»: each term emphasizes qualitative excellence. The meats are not lean or common, but fatty, rich in flavor, and sourced from the finest cuts. The wines are not plonk, but mature vintages, aged and carefully filtered to achieve their aromatic perfection. In a culture where meat was a rare luxury, reserved for special occasions, and where fine wine symbolized prosperity, this description evokes absolute abundance, the end of all scarcity.

This emphasis on quality and quantity is not merely decorative. It reveals something fundamental about how God gives. The Lord does not give sparingly, does not distribute sparingly, does not calculate his gifts. His generosity is excessive, boundless, almost scandalous. This is the logic of the Kingdom that Jesus will adopt in his parables : the measure well packed, shaken, overflowing; the hundred sheep from which one goes to look for the hundredth lost one; the workers of the last hour paid as those of the first.

This divine abundance stands in stark contrast to the historical experience of the people of Israel at the time Isaiah prophesied. Exile had meant deprivation, hunger, thirst, and want. The return from exile did not immediately bring the promised prosperity. Jerusalem remained in ruins, harvests were meager, and daily survival remained a struggle. In this context of real scarcity, Isaiah's vision offers a striking contrast: God prepares not the bare minimum of sustenance, but the ultimate feast.

This promise of abundance is not an escapism into fantasy, an illusory consolation for empty stomachs. It affirms a profound theological truth: the purpose of creation is not precarious survival, but a flourishing, joyful, and celebrated life. Present deprivation is not God's original design, but a consequence of sin and the disorder introduced into creation. The eschatological feast restores the original divine plan of a fulfilled, content, and happy humanity.

This vision has immediate practical implications for our spiritual lives. It invites us to reject all forms of spiritual Jansenism, that religious tendency which sees austerity, deprivation, and suffering as intrinsic values, as privileged paths to God. Not that asceticism has no place in the spiritual journey, but it is never an end in itself, only a temporary means of purification or learning. The final destination is not fasting, but feasting.

This statement also revolutionizes our relationship with material goods. Isaiah's feast is not spiritualized, ethereal, or immaterial. It engages the senses: taste, smell, and touch. It affirms that material creation is good, that sensory pleasure has its legitimacy, that joy Bodily possessions are not suspect. Of course, disordered attachment to things, gluttony, and avarice are condemned. But what is rejected is the disorder of selfish appropriation, not kindness intrinsic to the creatures and their use.

In our contemporary Western societies, marked simultaneously by frenetic overconsumption and degrowth movements, this biblical vision offers a precious balance. It neither sanctifies compulsive accumulation nor ascetic austerity as absolute values. It invites us to receive the goods of creation as gifts to be shared, to savor them with gratitude rather than accumulate them possessively, to celebrate in community rather than consume them in isolation.

The abundance of the divine feast also raises the question of distributive justice. If God prepares such a banquet for all, how can we tolerate some lacking necessities while others squander the superfluous? The eschatological feast is not an excuse to accept present injustice, but rather a criterion for judgment and a call to action. Every time we exclude someone from our table, refuse to share our bread, or close our door to the hungry, we contradict the prophetic vision and delay the coming of the Kingdom.

The story of Christianity is filled with examples of believers who took this vision of shared abundance seriously. From the early Christian communities who pooled their possessions to the religious orders that took vows of’hospitality, Through countless charitable initiatives, soup kitchens, and food banks, the shared table has become a tangible sign of the anticipated Kingdom. Every meal offered to a poor person, every door opened to a stranger, every selfless act of sharing is a small fulfillment of the feast prophesied by Isaiah.

But the material abundance described by the prophet also points to an even more essential spiritual abundance. The meats and wines are symbols of deeper realities. The true feast is communion with God himself, participation in his divine life, the fulfillment of all our deepest longings. As he will say Saint Augustine Centuries later, our hearts are restless until they find peace in God. Isaiah's feast promises this final rest, this ultimate peace, this complete fulfillment of all our true desires.

This spiritual dimension of the feast is particularly evident in the Christian Eucharistic tradition. Every celebration of the Eucharist It is a foretaste of the eschatological banquet, a sacramental anticipation of the final feast. The consecrated bread and wine are not mere memorial symbols, but sacramental realities that already unite us to Christ and, through him, to Trinitarian communion itself. By receiving Communion, we already feast on the holy mountain, even if the fullness of communion remains to come.

Universal communion: when borders collapse

The second major theme of this prophetic text concerns the radical universality of the divine invitation. «For all peoples,» Isaiah repeats, emphasizing this breathtaking scope. This universality is not simply a quantitative expansion—inviting more people—but a qualitative transformation of the very understanding of salvation.

In the historical context of Israel, this assertion is revolutionary. The Jewish people built their identity on a distinctive, separate, and sacred identity in the original sense of "set apart." The laws of purity, dietary restrictions, circumcision, and the Sabbath all contributed to marking a radical difference between Israel and the pagan nations. This distinction was not ethnic contempt, but a particular calling: to be "a kingdom of priests and a holy nation," bearing witness to the one true God amidst idolatry.

However, the feast foretold by Isaiah abolishes this separation. Not that Israel's identity is dissolved or denied, but rather it finds its fulfillment in a universal mission. The holy mountain, Zion, becomes the center toward which all nations converge. The light that was to emanate from Israel finally reaches the ends of the earth. The particular election reveals its universal purpose.

This dynamic of universal openness runs throughout biblical history, but it is often thwarted, forgotten, betrayed. After exile, a tendency toward identity withdrawal develops, understandable after the trauma experienced, but contrary to the prophetic vocation. Some currents of post-exilic Judaism insist on exclusivity, ethnic purity, and separation from the nations. Others, like that of Isaiah, maintain the universalist vision.

THE Christianity The nascent Church will inherit this tension and will have to resolve it painfully. The debate that agitated the early Church—should converted pagans be circumcised? Should they observe Jewish dietary laws?—is precisely the debate about the universality of the divine invitation. Peter's vision in Joppa, where God shows him a sheet filled with unclean animals and commands him to eat, directly responds to the promise of Isaiah. The table is open to all, without any precondition of ethnicity or ritual conformity.

This universal openness has immense practical consequences for our understanding of the Church and the Christian mission. The Church is not a private club of spiritually privileged individuals, but the community anticipating the universal feast. Its vocation is not to erect walls to protect its purity, but to set tables to welcome the multitude. Every time the Church excludes, discriminates, or rejects, it betrays the prophetic vision and distances itself from its authentic identity.

Christian history is unfortunately replete with counter-testimonies to this universality. The Crusades, the Inquisition, the Wars of Religion, colonialism carried out in the name of evangelization, support given to oppressive regimes—all of this directly contradicts the open table of Isaiah. Every time Christians have used violence to impose their faith, every time they have justified exploitation or slavery, every time they have despised other cultures or religions, they have disguised the universal feast as a banquet reserved for the victors.

Conversely, the bright moments of Christianity These are the examples where this universality has been honored. Francis of Assisi sharing his table with lepers. Vincent de Paul organizing the first soup kitchens. The missionaries who learned local languages, respected cultures, and promoted the dignity of the people they encountered. Martin Luther King fighting so that everyone could sit at the same table, literally and figuratively. Mother Teresa gathering the dying from the streets of Calcutta so they would not die alone, without dignity.

This universality is particularly relevant to our contemporary Western societies, marked by the rise of nationalism, fear of foreigners, and the temptations of identity politics. Isaiah's feast is a prophetic response to all ideologies of exclusion. It proclaims that no nation has a monopoly on truth, that no culture is inherently superior, and that no people is destined to dominate others. All are invited, all have their place, and all participate equally in the final communion.

This does not mean that all ideas are equal, that all practices are legitimate, or that there is no objective truth. Universality is not relativism. But it affirms that God's truth transcends our particularities, that the Spirit blows where it wills, that God can speak in unexpected ways. It protects us from spiritual pride, that constant temptation to believe ourselves the only chosen ones, the only enlightened ones, the only saved ones.

This vision also has implications for our relationship with other religions. If the feast is "for all peoples," this necessarily includes men and women of all faiths or of no explicit faith. How are we to understand their place in the salvific plan? Christianity He affirms that Christ is the only mediator, the way, the truth, and the life. But he also recognizes that the Spirit of God is at work everywhere, that "seeds of the Word" exist in all cultures, and that God desires the salvation of all.

The council Vatican He outlined a theology of fulfillment that respects both the uniqueness of Christ and the universality of divine action. Other religious traditions may contain authentic elements of truth and holiness, while finding their fullest fulfillment in Christ. This position avoids the twin pitfalls of arrogant exclusivism (only Christians explicit ones are saved) and undifferentiated relativism (all religions are equal).

Isaiah's universal table thus invites us to a twofold fidelity: fidelity to our Christian identity, rooted in the confession of Jesus as Lord and Savior, and respectful openness to all those whom God invites to his feast by paths we may not necessarily know. It is a creative tension, sometimes uncomfortable, but faithful to the complexity of the divine mystery.

Victory over death: radical hope

The third point, and undoubtedly the most unsettling, concerns the announcement of the definitive disappearance of death. «He will make death disappear forever»: this concise statement contains such a radical hope that it defies our most fundamental experience. Death, this absolute certainty, this implacable truth, this inseparable companion of human existence, will be abolished.

To grasp the full significance of this promise, we must first understand what death represents in the human condition. It is not simply the biological end of the organism, the cessation of vital functions. It is the ultimate horizon that structures our entire existence, the absolute limit that lends weight to all our choices, the underlying anxiety that haunts our consciences. As Heidegger wrote, we are "beings-towards-death," defined by our mortal condition.

Death separates the living from the dead, creates an unbridgeable abyss, and severs even the most precious relationships. It generates existential angst, a sense of the absurd, and the vertigo of nothingness. All civilizations have developed strategies to come to terms with death: funeral rituals, beliefs in the afterlife, philosophies of Stoic wisdom, but all recognize its inescapable and mysterious nature.

In the biblical tradition, death is ambivalent. On the one hand, it is considered natural, inherent in the human condition. Man is taken from dust and will return to dust. On the other hand, especially in the narratives of Genesis, Death is presented as a consequence of original sin. "The day you eat of it, you will surely die," God warns concerning the tree of knowledge. Physical death then appears as a manifestation and punishment of spiritual death, the separation from God.

The Old Testament gradually develops a reflection on the afterlife. The earliest texts evoke Sheol, a shadowy and neutral abode of the dead, without true life or true death. Gradually, particularly in the later apocalyptic and wisdom literature, the belief in a resurrection of the righteous emerges. Daniel's book asserts that "many of those who sleep in the dust will awaken." Second Book of Maccabees tells of the martyrdom of the seven brothers who die affirming their faith in the resurrection.

But nowhere before Isaiah 25 do we find this radical affirmation of the universal abolition of death. Not a personal survival for a privileged few, not an immortality of the soul in the Greek manner, but the suppression of death itself as a cosmic reality. It is a dizzying, almost unbelievable hope that anticipates the Christian revelation of the resurrection of Christ and the promise of a universal resurrection.

This promise finds its fulfillment in the Pascal's mystery. Christ dies and rises again, not to escape death, but to pass through it and conquer it from within. His resurrection is not a temporary resuscitation like that of Lazarus, but a qualitative transformation, the entry into a new life that death can no longer touch. Paul can then write: «Where, O death, is your victory? Where, O death, is your sting?» Death has lost its ultimate power, its final word.

This victory over death radically transforms the Christian's relationship to finitude. Death remains a reality we must face, a painful separation, a dark passage. But it is no longer the absolute enemy, the final end, the ultimate defeat. It becomes a passage, a gateway, a birth into a fuller life. Saint Francis He will affectionately call her "our sister, bodily death".

This transformation is not merely psychological consolation or a trick to tame anguish. It is an ontological affirmation of the nature of reality. Death does not have the last word because love is stronger than death, because divine life is indestructible, because communion with God transcends all destruction. He who abides in love abides in God, and God is life.

This hope has immense practical consequences for how we live our mortal existence. If death is not the absolute end, if our relationships survive the grave, if our acts of love have eternal significance, then nothing is in vain, nothing is absurd, everything takes on a glorious weight. The smallest act of kindness, the most discreet service, the humblest prayer have definitive meaning because they are inscribed in eternity.

This vision also transforms how we accompany the dying. Faced with someone nearing death, we are not reduced to helpless silence or empty consolations. We can bear witness to the hope that dwells within us, accompany them through their passing with confidence, celebrate the life that has been lived while affirming that it is not lost. Christian funeral rites are not simply farewell ceremonies, but celebrations of the eternal life that has begun.

Of course, this hope does not negate the pain of grief. Mourning our dead is not a lack of faith; it is honoring the reality of separation and the authenticity of our emotional bonds. Christ himself wept before the tomb of Lazarus. Christian hope does not transform us into impassive stoics, but it situates our grief within a horizon that transcends finitude. We weep, but not «like those who have no hope,» as Paul would say.

The legacy of the fathers and the voice of tradition

This prophetic vision of Isaiah did not remain a dead letter in the Christian tradition. The Church Fathers, those early theologians who developed Christian doctrine, commented extensively on and meditated upon this passage, finding in it an essential key to understanding the mystery of salvation.

Saint Augustine, In his commentaries on the Psalms and in The City of God, he frequently returns to this image of the eschatological feast. For him, the food promised by Isaiah is above all Christ himself, spiritual nourishment that definitively satisfies. hunger of truth and love that dwells in the human heart. The feast symbolizes heavenly bliss, that face-to-face vision of God which constitutes perfect happiness. The rich meats and heady wines represent the fullness of divine contemplation., joy without mixing those who participate in the Trinitarian life.

Saint John Chrysostom, the great preacher of Antioch and later Constantinople, saw in this feast a prefiguration of the Eucharist. Each Eucharistic celebration makes present the promise of Isaiah, offering the faithful the body and blood of Christ, food for immortality. The table set on the holy mountain is the altar where the Lord's ever-renewed sacrifice is celebrated. This universal invitation foreshadows the Church's openness to all nations, the transcendence of the old law in the new Covenant.

Origen, the great Alexandrian exegete, offers a more complex allegorical interpretation. The mountain represents the peaks of spiritual contemplation, accessible to those who undertake the ascent through moral purification and intellectual enlightenment. The meats and wines symbolize the various forms of spiritual nourishment: the Scriptures for beginners (milk), the profound mysteries for the advanced (solid food). The veil of mourning that will be removed represents the ignorance that obscures our understanding as long as we live in the flesh.

In the Middle Ages, Thomas Aquinas incorporated Isaiah's vision into his monumental theological synthesis. In the Summa Theologica, he carefully distinguishes between the imperfect beatitude possible here below and the perfect beatitude of eternal life. Isaiah's feast describes this eschatological beatitude, characterized by the beatific vision (seeing God as he is)., the resurrection glorious of bodies, and the communion of saints. Thomas insists on the corporeal character of this beatitude: separated souls enjoy the vision of God, but the fullness of joy requires the resurrection of the body.

Christian liturgical tradition has strategically incorporated this passage into its celebrations. It is often proclaimed at funerals, offering the bereaved a word of consolation and hope. It also resonates during times of eschatological preparation as Advent, where the Church awaits the coming of the Kingdom. Some liturgies use it for the feasts of All Saints' Day, celebrating the heavenly feast where the saints are already gathered.

Monastic spirituality has given particular thought to this text. Monks, who live a life of renunciation and austerity, do not celebrate fasting for its own sake, but in anticipation of the feast. Their asceticism is a preparation, a sharpening of the spiritual appetite, a purification of the inner palate to fully savor the divine nourishment. The monastic refectory, where monks silently share their meal while listening to the reading of Scripture, humbly prefigures the heavenly banquet.

In the mystical tradition, this feast has inspired fervent descriptions of union with God. John of the Cross speaks of the "banquet of loves" where the soul of the bride tastes the delights of the divine presence. Teresa of Avila He describes the "mansions" of the inner castle as a progression toward the wedding feast where Christ unites definitively with the soul. These mystics do not simply wait passively for the eschatological feast; they experience its anticipations in their contemplative experiences.

The Protestant Reformation maintained this eschatological hope while purifying it of certain interpretations deemed excessive. Luther emphasized that the feast is not earned through our works, but freely offered by divine grace. Calvin insisted on the sovereignty of God, who presides over the banquet and freely chooses his guests. Both reformers maintained the importance of the Eucharist as a foretaste of the heavenly feast, even if they dispute its theological modalities.

Paths of inner transformation

How can this magnificent text become not only a distant consolation, but an active principle for transforming our daily lives? Here are some concrete ways to integrate this prophetic vision into our spiritual journey.

Begin by cultivating the art of daily gratitude. Every meal you eat, even the simplest, can become a reminder of the promised feast. Before eating, take a moment to recognize that all food is a gift, that sharing a meal anticipates the final communion. Transform your meals into mindful moments rather than mechanical refueling.

Practice the’hospitality Be practical. Open your table to those who are alone, isolated, excluded. Regularly invite people different from yourself, step outside your usual circle. Each invitation is a small embodiment of the universal feast, each welcome repeats the divine gesture of inclusion. Start modestly: one person a month, a couple every two months, according to your means.

Develop a practice of meditating on death that is not morbid but liberating. Take a few minutes each week to contemplate your mortality, not to become anxious, but to put superficial concerns into perspective and prioritize your needs. Ask yourself: "If I died tomorrow, what would I regret not having done?" Then act accordingly.

Learn to cry healthily. Our culture values emotional control to such an extent that it makes the authentic expression of sadness suspect. Yet, tears are human, necessary, and therapeutic. Give yourself permission to cry for your losses, your disappointments, your suffering. And in these moments of vulnerability, remember the promise: God will wipe away those tears.

Get involved in the fight against hunger and exclusion. Find a local organization that distributes meals, a food bank, a soup kitchen. Give your time, your money, your skills. Every person fed, every hungry person satisfied, is a sign of the coming Kingdom.

Work on your relationship with abundance and scarcity. If you live comfortably, regularly question your level of consumption and your accumulation of superfluous possessions. Practice voluntary fasting, not out of contempt for the body, but to awaken your spiritual hunger and your solidarity with those who fast involuntarily. If you live in poverty, don't let lack define your identity; remember the promise of abundance that awaits you.

Create personal rituals around the Eucharist. If you are Catholic, participate more consciously in Mass, recognizing in each communion a foretaste of the eschatological feast. If you are Protestant, honor the Lord's Supper as a special moment of anticipation of the Kingdom. Whatever your tradition, do not let these sacraments become routine or meaningless.

The moment of decision

We have now reached the end of this journey through the dazzling verses of Isaiah. What can we take away from this prophetic vision that has traversed millennia without losing its overwhelming power?

First, this: God's plan for humanity is not resigned austerity, precarious survival, or a diminished existence. It is shared abundance., joy Community, life unfolding in all its fullness. The feast is not a pious metaphor, but the revelation of the true destiny of our condition. We are made for communion, for celebration, for life without end.

Furthermore, this promise is not reserved for a privileged few, a spiritual elite, or a particular people. It is addressed to "all peoples," without distinction of race, class, or religious origin. The universality of the divine invitation destroys all our barriers, our exclusions, our artificial hierarchies. Everyone has a place at the table, everyone is expected, everyone is desired.

Finally, and perhaps most breathtakingly, this vision affirms that death itself, this seemingly absolute certainty, will be vanquished, abolished, swallowed up in the victory of life. This promise radically transforms our relationship to existence. Nothing is in vain, nothing is lost, everything is recapitulated and transfigured in divine eternity.

But this hope is not an invitation to passive inaction, to resignation in the face of present injustices in the name of a future bliss. On the contrary, it calls us to embody, right now, in our daily choices, the reality of the coming Kingdom. Every gesture of’hospitality, Every act of sharing, every consolation offered, every dried tear contributes to the coming of the prophesied feast.

The world we live in often seems to directly contradict Isaiah's vision. Wars are multiplying, famines persist, inequalities are deepening, exclusion is intensifying, and death relentlessly reaps its harvest. Faced with this brutal reality, the prophetic promise may seem naive, unrealistic, and out of touch. Yet, it is precisely in this wounded world that Christian hope must shine forth.

To be a Christian is to believe, against all odds, that love is stronger than hate, that life triumphs over death, that communion will overcome division. It is to refuse to resign oneself to evil as an inevitable fate, and to work tirelessly to weave bonds of brotherhood, to build spaces for sharing, to anticipate in concrete ways the promised Kingdom.

This task is immense, often daunting, and seemingly disproportionate to our limited resources. But let us remember: we do not work alone. The Spirit who inspired Isaiah continues to breathe hope into the hearts of believers. Christ, who conquered death, walks with us on the difficult paths. The community of witnesses, living and dead, surrounds and supports us.

So, will we dare to believe in this impossible feast? Will we dare to live as if the promise were already being fulfilled? Will we dare to set tables, wipe away tears, celebrate life in the very midst of death? It is to this prophetic audacity that we are summoned, not by an overwhelming moral imperative, but by a joyful invitation to participate in the most extraordinary work of all: the transfiguration of the world.

The feast is prepared. The table is set. The invitation is extended. Will we come? Will we bring other guests with us? Will we begin to taste now the first fruits of the eternal banquet? The answer belongs to each of us, but it engages our entire existence, until the day we finally enter the banquet hall and at last recognize the face of the One who will wipe away every tear from our eyes.

Practices for moving forward

Cultivating presence at the table : transform each meal into a conscious moment of gratitude, slow down the pace, savor, share, avoid food isolation in front of screens.

Practicing’hospitality monthly : identify a person who is isolated or different from you and invite them to share a simple but friendly meal, creating bridges between solitudes.

Meditate regularly on finitude : dedicate ten minutes a week to contemplating one's death in order to better live in the present, prioritize one's needs according to what is essential.

To take concrete action against hunger : giving two hours a month to a food distribution organization, or financially supporting local charitable activities according to one's means.

To participate consciously in the Eucharist : to spiritually prepare for each communion with a few minutes of reflection, recognizing in it the foretaste of the heavenly feast.

Welcoming one's emotions with kindness : giving oneself permission to mourn one's losses without shame, while keeping the hope of the promised divine consolation.

Create community sharing spaces : organize or join parish shared meals, open guest tables, moments of intergenerational or intercultural conviviality.

References

Book of the Prophet Isaiah, chapters 24-27, section known as "Apocalypse of Isaiah", sixth century BC.

Saint Augustine of Hippo, The City of God, books XIX-XXII on eschatological beatitude and the heavenly feast, fifth century.

Saint Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, Prima Secundae, questions 1-5 on beatitude, and Tertia Pars on the sacraments as an anticipation of the Kingdom.

Paul Beauchamp, Both Testaments, volume 2, on the prophetic theology of universalism and eschatological salvation.

Pierre Grelot, Jewish hope at the time of Jesus, for the historical and theological context of messianic hope in Second Temple Judaism.

Jean-Pierre Sonnet, The alliance of speech, on the literary and theological structure of prophetic texts and their eschatological scope.

Council Vatican II. Dogmatic Constitution Lumen Gentium on the Church, chapter VII concerning the eschatological character of the Church and its orientation towards the definitive Kingdom.

Jean Daniélou, Essay on the mystery of history, for a theology of history oriented towards the eschatological fulfillment of divine promises.