Reading from the Letter of Saint Paul the Apostle to the Romans

Brothers,

for those who are in Christ Jesus,

there is no more condemnation.

For the law of the Spirit who gives life in Christ Jesus

freed you from the law of sin and death.

For when God sent his own Son

in a carnal condition similar to that of sinners

to overcome sin,

he did what the law of Moses

could not do because of human weakness:

He condemned sin in the carnal man.

He wanted the requirement of the Law to be fulfilled in us,

whose conduct is not according to the flesh but according to the Spirit.

For those who conform to the flesh

tend towards what is carnal;

those who conform to the Spirit

tend towards what is spiritual;

and the flesh tends toward death,

but the Spirit tends toward life and peace.

For the mind of the flesh is hostile to God,

she does not submit to the law of God,

she's not even capable of it.

Those who are under the influence of the flesh

cannot please God.

But you are not under the influence of the flesh,

but under that of the Spirit,

since the Spirit of God dwells in you.

Whoever does not have the Spirit of Christ does not belong to Him.

But if Christ is in you,

the body, it is true, remains marked by death because of sin,

but the Spirit gives you life, because you have been made righteous.

And if the Spirit of him who raised Jesus from the dead

lives in you,

the one who raised Jesus Christ from the dead

will also give life to your mortal bodies

through his Spirit who dwells in you.

– Word of the Lord.

The Power of the Spirit: Living the Resurrection in the Heart of Everyday Life

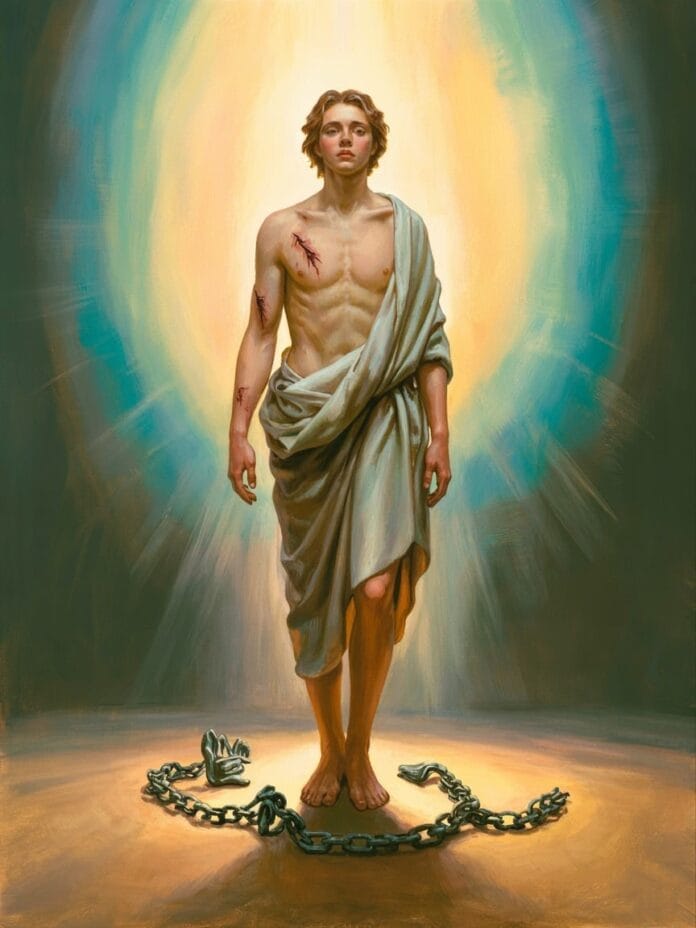

Discover how the Holy Spirit radically transforms your existence by breaking the chains of sin and death

In this luminous passage from the Epistle to the Romans, Paul reveals a shattering truth: the same Spirit who resurrected Jesus dwells within you. This promise does not concern some distant future, but radically transforms your present. For all those seeking to understand their Christian identity and fully live their vocation, this text offers the keys to authentic liberation. The apostle unveils the spiritual dynamic that allows us to move from a life marked by condemnation to one inhabited by the very power of the Resurrection.

We will first explore the historical and theological context of this major letter, then analyze the central tension between flesh and Spirit. Next, we will unfold three essential axes: liberation from condemnation, divine indwelling, and the promise of bodily resurrection. Finally, we will offer concrete ways to embody this spiritual reality in your daily life.

Context

The Letter to the Romans, written by Paul around 57-58 AD, constitutes the most systematic exposition of Pauline theology. The apostle writes to a community he did not found, established in the heart of the Roman Empire, composed of Christians of Jewish and pagan origin. This letter aims to prepare for his future visit while clarifying the foundations of the Christian faith in the face of tensions between Jews and Gentiles.

Chapter 8 marks a theological climax after the developments on justification by faith, universal sin, and the inner struggle of the believer described in chapter 7. Paul moves here from the analysis of the fallen human condition to the triumphant proclamation of life in the Spirit. This passage answers a fundamental question: how can we concretely live this justification obtained by faith in Christ?

In the Catholic liturgy, this text resonates on the Fifth Sunday of Lent or in celebrations dedicated to the Holy Spirit. It constitutes one of the most cited passages for understanding Christian pneumatology and the transformation that the Spirit operates in the lives of the baptized.

The text itself is structured in three movements. First movement: the announcement of non-condemnation and liberation by the Spirit. Second movement: the description of the radical opposition between the flesh and the Spirit, between two incompatible logics of life. Third movement: the affirmation of the indwelling of the Spirit and the promise of a future bodily resurrection.

Paul uses precise and contrasting vocabulary. On the one hand, "flesh" refers not to the physical body but to human existence marked by sin, withdrawn into itself, incapable of submitting to God. On the other, "Spirit" represents the active presence of God who transforms the believer from within, communicating to him the very divine life.

The phrase "there is no longer condemnation" opens the chapter with extraordinary liberating force. After describing man's condition under sin and the Law, Paul proclaims a total rupture. The "law of the Spirit" replaces the powerless Mosaic Law. This radical novelty stems from the sending of the Son "in the flesh like that of sinners," an anticipation of the theology of the Incarnation.

The central issue is clear: living "according to the Spirit" rather than "according to the flesh." This alternative does not concern two categories of people, but two opposing existential dynamics. The flesh leads to death, the Spirit to life and peace. Paul does not propose a metaphysical dualism but describes a moral and spiritual tension at the heart of Christian existence.

Analysis

The central idea of this passage lies in the revolutionary affirmation that the Spirit of God now dwells within believers, producing a radical ontological transformation. This indwelling is not metaphorical but real, concrete, and operative. It constitutes the foundation of Christian identity and the source of all authentic spiritual life.

Paul establishes a bold theological equation: "the Spirit of God," "the Spirit of Christ," and "Christ in you" designate the same reality. This identification reveals the depth of the Trinitarian mystery lived in the experience of the first Christians. The Spirit is not an impersonal force but the very presence of the Risen One acting in his disciples.

The central paradox lies in the coexistence of two seemingly contradictory realities: "the body remains marked by death because of sin, but the Spirit makes you live." This tension between the "already" and the "not yet" characterizes all of Pauline theology. Believers already live the life of the Resurrection while awaiting the final transformation of their mortal bodies.

This spiritual dynamic is based on a logic of replacement: the "law of the Spirit" liberates from the "law of sin and death." Note the wording: it is not human effort that produces this liberation, but a new, higher law, a divine life force that breaks the chains of the fallen human condition.

The Pauline argument is based on the failure of the Mosaic Law. Not that it is bad in itself, but that it is powerless "because of human weakness." The flesh, that is, man left to himself, cannot fulfill the divine requirements. Only the sending of the Son in the human condition and the gift of the Spirit make this transformation possible.

The existential scope of this truth overturns the Christian's understanding of himself. He is no longer defined by his failures, his weaknesses, his mortality, but by the Spirit who dwells within him. His deepest identity lies not in what he does but in the One who lives within him. This revelation frees him from an anxious quest for perfection through his own strength.

Theologically, Paul here develops the foundations of a supernatural anthropology. The human being is not simply a natural creature but a being destined for divinization, for participation in divine life itself. The Spirit does not come from the outside but transforms from the inside, communicating a new life, a new capacity to love, to know God, to live according to his will.

The pneumatological dimension is articulated with Christology: the Spirit does not act independently of Christ but actualizes the presence of the Risen One in the Church and in each believer. This unity between Christology and pneumatology avoids two pitfalls: a distant Christ in the past or a Spirit disconnected from the historical event of Jesus.

Liberation from Conviction: A New Identity

The initial statement, "there is no longer condemnation," sounds like a definitive acquittal. In the legal context of the time, condemnation implied exclusion, public shame, and sometimes death. Paul proclaims the total abolition of this verdict for those who are "in Christ Jesus." This technical expression designates incorporation into Christ through baptism, mystical union with him.

This liberation does not result from an arbitrary amnesty but from a victory over sin itself. God has "condemned sin in the flesh" by sending his Son. The paradoxical expression indicates that the condemnation no longer falls on the sinner but on sin itself, defeated in the flesh of the crucified Christ. This subtle but crucial distinction is the foundation of all Christian anthropology: man is not identified with his sin.

The "law of the Spirit" introduces a new regime. Unlike the Mosaic Law, which prescribed external commandments, this interior law of the Spirit transforms the heart, making possible what was impossible. It fulfills Ezekiel's prophetic promise: "I will give you a new heart and put a new spirit within you." Obedience then becomes no longer constraint but joyful spontaneity.

This liberation concerns all areas of existence. Liberation from the guilt that paralyzes, from the fear of judgment that distresses, from the self-obsession that imprisons. The Christian discovers an inner freedom that no longer depends on external circumstances but on the stable presence of the Spirit within him.

Concretely, this truth transforms the way we experience failures, weaknesses, and temptations. Instead of a vicious cycle of falling and guilt, a path of constant recovery in mercy opens up. Not that sin becomes insignificant, but it no longer defines the deepest identity of the believer. He can look lucidly at his faults without despair, knowing that they do not have the last word.

This new identity based on non-condemnation also implies a different view of others. If God no longer condemns, who am I to condemn? This logic of mercy received must translate into mercy given, breaking the spirals of judgment and rejection that fragment human communities.

The Spirit's fulfillment of the "demand of the Law" reveals that the Christian life is not antinomic but transmoral. It does not reject the commandments but fulfills them on a higher level, not through outward conformity but through inward transformation. Love of God and neighbor, the summation of the entire Law, becomes possible because the Spirit pours out God's love in our hearts.

The Divine Inhabitation: The Inner Temple

Paul insists that "the Spirit of God dwells in you." This verb "dwell" implies a stable, lasting, non-transitory presence. The Spirit does not come to visit occasionally but establishes his dwelling in the believer. This reality overturns the concept of the sacred: the true temple is no longer a stone building but the human person himself.

This indwelling radically distinguishes the Christian experience from all natural religiosity. It is not a matter of reaching out to a distant God through ascetic efforts, but of welcoming the One who is already there, in the most intimate part of oneself. Spiritual life then becomes no longer a heroic conquest but a recognition of the Presence already given.

The expression "Whoever does not have the Spirit of Christ does not belong to Him" establishes a criterion of ecclesiological belonging. Being a Christian is not defined primarily by external practices or intellectual adherence, but by this interior presence of the Spirit. This objective criterion remains mysterious because only God searches hearts, but it guarantees that reality always surpasses appearances.

This divine presence produces concrete effects. The Spirit "makes you live" in the present, not only in an eschatological future. This life designates more than biological existence: divine life itself, participation in the Trinitarian life, the capacity to love as God loves, to know as God knows, to act as God acts.

The identification between "the Spirit of Christ" and "Christ in you" reveals the profound unity between Christology and pneumatology. The risen Christ is not absent but present through his Spirit. This spiritual presence is no less real than the historical presence of Jesus in Galilee and Judea, but it takes on a new, universal, interior form.

In spiritual practice, this truth transforms prayer. Prayer is no longer about establishing communication with an external and distant God, but about becoming aware of the Spirit who prays within us, who groans within us, who intercedes within us. Saint Paul will say this explicitly a few verses later: "The Spirit helps us in our weakness, because we do not know how to pray as we ought."

This inhabitation also establishes the inalienable dignity of each person. If the Spirit of God dwells in each person, every human being becomes sacred, inviolable, and worthy of the greatest respect. This anthropological vision is radically opposed to any instrumentalization of the person, to any reduction of man to his functions or performances.

The Promise of Resurrection: The Eschatological Horizon

The pinnacle of Paul's argument culminates in this extraordinary statement: "He who raised Jesus from the dead will also give life to your mortal bodies through his Spirit who dwells in you." This promise does not concern a disembodied spiritual survival but a glorious transformation of corporeality itself.

The Spirit who now dwells in believers is the earnest, the pledge, of the future resurrection. The same power that snatched Jesus from the tomb will operate for all those in whom he dwells. This continuity between the present action of the Spirit and the final resurrection guarantees the fulfillment of the promise. God has already begun what he will gloriously complete.

Paul maintains a creative tension between the present and the future. "The body remains marked by death because of sin": the mortal condition remains, believers experience illness, aging, physical death. But this painful reality is not the final word. The Spirit is already working on the transformation that will culminate in the resurrection.

This bodily hope distinguishes the Christian faith from Platonic dualism, which despised the body as a prison for the soul. For Paul, the body is not evil in itself, but rather intended for glorification. The resurrection of Christ shows that matter itself is called to transfiguration, that the created world participates in divine salvation.

This eschatological perspective transforms the way we look at present suffering. The pains of the body and the limitations of mortality are not denied but are put into perspective in the face of the glory to come. In the following chapter, Paul will affirm that "the sufferings of this present time are nothing compared to the glory that will be revealed to us."

Concretely, this promise establishes a paradoxical attitude toward the body. On the one hand, respect and care for the body as a temple of the Spirit, destined for resurrection. On the other hand, relativization of physical appearances, health, and youth, knowing that the glorious body will infinitely surpass the current body. This dual attitude avoids the contemporary obsession with the perfect body while rejecting contempt for the body.

The horizon of bodily resurrection also implies a social and cosmic vision. If bodies are resurrected, matter is saved, and all of creation participates in redemption. This perspective is the foundation of an authentic Christian ecology: the world is not destined to disappear but to be transfigured, renewed, and glorified.

Tradition

This theology of the Spirit dwelling in believers runs through the entire Christian tradition. The Fathers of the Church developed this Pauline intuition in their doctrine of divinization. Saint Athanasius of Alexandria formulated the principle thus: "God became man so that man might become God." The indwelling of the Spirit constitutes precisely the means of this progressive divinization.

Saint Augustine, in his commentaries on the Epistle to the Romans, insists on the gratuitousness of this divine presence. The Spirit is not granted as a reward for human merits but precedes and makes possible every good work. This absolute primacy of grace will found Augustinian theology, which will profoundly influence the Christian West.

The monastic tradition, particularly in the Egyptian desert, sought to concretely experience this reality of the inner Spirit. The Desert Fathers taught attention to the heart, listening to the divine presence within. Prayer of the heart, hesychasm in the Eastern tradition, aims precisely to become aware of this permanent indwelling of the Spirit.

Thomas Aquinas, in his theology of the gifts of the Holy Spirit, systematizes this divine presence. He distinguishes between the presence of God through immensity in every creature and the special presence through grace in the righteous. The latter constitutes a new, personal, transforming presence, through which God becomes knowable and lovable in an intimate way.

Ignatian spirituality, with its discernment of spirits, is based on the conviction that the Spirit guides the believer internally. The Spiritual Exercises of Ignatius of Loyola aim to enable the retreatant to recognize the promptings of the Spirit in order to better follow His guidance in the concrete choices of life.

More recently, the Second Vatican Council, in its dogmatic constitution Lumen Gentium, took up this Pauline theology to describe the Church as a temple of the Spirit. The council affirmed that the Spirit dwells in the Church and in the hearts of the faithful as in a temple, guiding, sanctifying, and strengthening the Christian community.

John Paul II, in his encyclical Dominum et Vivificantem, elaborates at length on this presence of the Holy Spirit in the believer and in the Church. He shows how the Spirit actualizes Christ's redemption, applying the fruits of Easter to each generation. This renewed pneumatology has profoundly influenced contemporary Catholic spirituality.

Meditation

To embody this reality of the Spirit dwelling within you, here is a progressive seven-step journey that you can integrate daily into your spiritual life and your way of being in the world.

Step One: Begin each day with an awareness of the Presence. Before rising, in the stillness of the morning, affirm to yourself, “The Spirit of God dwells within me.” Let this truth penetrate your consciousness, not as an abstract idea but as a living reality.

Step Two: In times of temptation or difficulty, remember that you are no longer under condemnation. Instead of wallowing in guilt, welcome the mercy that sets you free. Simply say, "I am freed from condemnation; the Spirit dwells within me."

Step three: Practice self-examination not as an exercise in guilt but in discernment. Identify in your day what was based on the logic of the flesh (withdrawal, selfish pursuit, closure to others) and what was based on the Spirit (openness, giving, inner peace).

Step Four: Develop an awareness of your body as a temple of the Spirit. Take care of your health, your rest, and your diet, not out of narcissistic concern but out of respect for this divine dwelling place. Your body participates in your spiritual life.

Step Five: In prayer, practice inner listening. After presenting your requests, remain silent, attentive to the movements of the Spirit within you. Note the thoughts, desires, and emotions that emerge, so that you can discern them later.

Step Six: Translate this spiritual reality into your relationships. If the Spirit dwells in you, he also dwells in every person you encounter. Seeing others as temples of God will radically transform the way you relate to each other.

Step Seven: Nourish your hope of resurrection. In the face of illness, aging, or hardship, anchor yourself in the promise that your mortal body will receive life. This hope changes everything, even if it does not eliminate the present suffering.

Conclusion

This passage from the Epistle to the Romans reveals a truth as simple as it is incredible: the Spirit who resurrected Jesus dwells within you. This statement is not a matter of blissful optimism or spiritual illusion, but rather the very heart of the Christian faith. Your true identity is not defined by your failures, your weaknesses, your mortality, but by this divine Presence that dwells within you and transforms you from within.

The transformative power of this message lies in its concrete and present nature. It is not a matter of passively waiting for a future salvation, but of living now the new life that the Spirit communicates. Every decision, every relationship, every trial becomes an opportunity to choose between the logic of the flesh and that of the Spirit, between deadly closure and life-giving openness.

This revelation calls for a revolution in the way you look at yourself and others. If the Spirit of God dwells within you, you are infinitely more than you appear; you carry within you an inalienable dignity, a divine vocation. This awareness must translate into renewed confidence, spiritual boldness, and an inner freedom that no longer depends on external circumstances.

The final invitation is clear: let the Spirit who dwells within you concretely transform your existence. Not through an exhausting volitional effort, but through a docile openness, a trusting availability to divine action. Authentic Christian life springs from this mysterious collaboration between divine grace and human freedom, between God's initiative and your response. Welcome each day this Presence which wants to lead you from death to life, from condemnation to freedom, from sin to holiness. The Spirit who resurrected Christ is already working in you: let him accomplish his work of transformation until the full manifestation of the glory to come.

Practical

- Begin each morning by affirming, “The Spirit of God dwells within me,” letting this truth penetrate your consciousness before any activity.

- In moments of guilt or failure, remind yourself, “There is no longer any condemnation for me in Christ,” thus breaking the cycle of paralyzing self-blame.

- Practice ten minutes of inner silence daily to listen to the promptings of Spirit, then record your insights in a spiritual journal.

- Consciously choose three times a day between the logic of the flesh and that of the Spirit, clearly identifying these two tendencies in your concrete decisions.

- Treat your body as a temple of the Spirit: adequate rest, healthy diet, regular exercise, from a spiritual and not narcissistic perspective.

- See each person you meet as inhabited by the Spirit, which will profoundly transform your way of relating and communicating.

- Meditate regularly on the promise of bodily resurrection, especially in times of illness or physical suffering, anchoring your hope in this certainty.

References

- Epistle of Saint Paul to the Romans, chapters 7-8, Liturgical Translation of the Bible (AELF), for the immediate context and theological progression of the Pauline argument.

- Saint Augustine, Treatise on Grace And Commentary on the Epistle to the Romans, essential patristic sources on the theology of grace and the Spirit in the Western tradition.

- Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, Ia-IIae, questions 109-114 on grace, and IIa-IIae, questions 8-45 on the gifts of the Holy Spirit, for medieval theological systematization.

- John Paul II, Encyclical Dominum et Vivificantem (1986), for contemporary magisterial teaching on the Holy Spirit and his action in the Church and in souls.

- Second Vatican Council, Dogmatic Constitution Lumen Gentium (1964), particularly chapters II and VII on the People of God and the Holy Spirit in the Church.

- Romano Guardini, The Lord, profound reflections on life in the Spirit and the spiritual transformation of the Christian from the perspective of the modern Catholic faith.

- Hans Urs von Balthasar, The Theology of History, for a theological understanding of eschatology and the promise of resurrection in the perspective of salvation history.

- Ignatius of Loyola, Spiritual exercises, especially the rules for discerning spirits, for the practical application of discerning the action of the Spirit in daily life.