Reading from the Letter of Saint Paul the Apostle to the Romans

Brothers,

we have a debt,

but it is not towards the flesh

to have to live according to the flesh.

For if you live according to the flesh,

you will die;

but if, by the Spirit,

you kill the deeds of sinful man,

you will live.

For all who are led by the Spirit of God,

These are the sons of God.

You have not received a spirit that enslaves you

and brings you back to fear;

but you have received a Spirit who has made you sons;

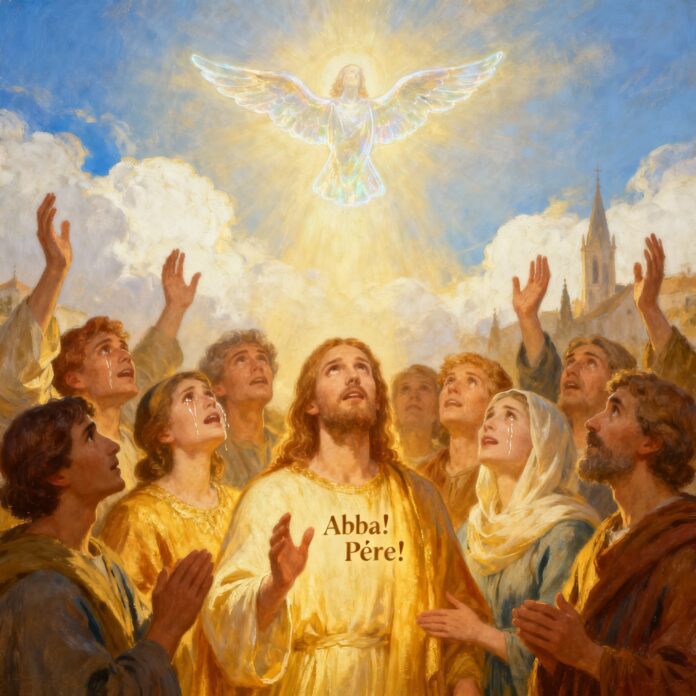

and it is in him that we cry out " Abba! ", that is to say: Father!

So it is the Holy Spirit himself who bears witness to our spirit

that we are children of God.

Since we are his children,

we are also his heirs:

heirs of God,

heirs with Christ,

if at least we suffer with him

to be with him in glory.

– Word of the Lord.

From Slavery to Sonship: How the Holy Spirit Transforms Our Identity

Discover why Paul calls God “Abba” and what this radically changes in your spiritual life.

In his letter to the Romans, Paul proposes a spiritual revolution: we are no longer slaves trembling before a distant master, but children adopted by God himself. This radical transformation is brought about by the Holy Spirit, who enables us to cry out "Abba!"—the intimate word Jesus used to speak to his Father. This passage overturns our understanding of the Christian life: living according to the Spirit is not a moral constraint, but the learning of a filial freedom that leads us toward the promised glory.

We will first explore the historical and theological context of this Pauline statement, then analyze the central dynamic of the text: the shift from fear to trust. We will then delve deeper into three essential dimensions: the freedom given by the Spirit, restored intimacy with God, and the glorious inheritance promised to children. Finally, we will discover how to put this divine sonship into practice in our daily lives.

Context: Paul writes to the Christians in Rome

When Paul wrote his letter to the Romans, probably around 57-58 CE from Corinth, he was addressing a community he had not yet personally visited. Rome, the capital of the Empire, was home to a diverse Christian community, made up of converts of both Jewish and pagan origins. Paul, the apostle to the nations, sought to establish the theological foundations of the Christian faith with a depth and systematicity unmatched in his other writings.

Chapter 8 of the Epistle to the Romans constitutes one of the high points of Pauline thought. After having developed at length justification by faith and liberation from sin, Paul now addresses life in the Spirit. This passage comes as a concrete answer to the existential question that every believer asks: how can we live this new spiritual reality on a daily basis?

The vocabulary Paul uses reveals a specific intention. He uses the Greek term "huiothesia," which referred to legal adoption in the Roman world. This notion had considerable legal significance: the adopted child became a full heir, just like a biological son. Paul thus borrows from the social vocabulary of his time to express a revolutionary spiritual reality.

The opposition between "flesh" and "Spirit" structures the entire passage. In Pauline language, the flesh does not simply designate the physical body, but the whole of human existence oriented towards itself, cut off from God, imprisoned by its own limitations. The Spirit, on the contrary, represents the divine power that comes to inhabit the believer and transform him from within.

The Aramaic word "Abba" occupies a central place. Jesus used it to address God, and the Gospels preserved this term in its original language, testifying to its importance. "Abba" combines childlike tenderness and filial respect. It is neither the simple "daddy" that is sometimes translated, nor the distant and formal "father," but an expression of trusting intimacy.

In the liturgical context, this passage is often proclaimed during feasts celebrating the Holy Spirit, notably Pentecost or the Trinity. It reminds us that the Christian life is not reduced to following an external moral code, but consists of living a filial relationship with God through the Spirit. This perspective radically changes our approach to prayer, ethics, and Christian hope.

Analysis: The dynamics of inner transformation

Paul frames his argument around a striking contrast: two modes of existence are opposed, one leading to death, the other to life. This opposition is not simply moral or behavioral; it touches on the very identity of the believer.

The first part of the text poses a paradoxical debt: we owe a debt, but not to the flesh. This surprising formulation reverses the usual logic. In ordinary human experience, it is precisely to our desires, our fears, our instincts that we seem to owe something. Paul asserts the opposite: we owe nothing to this logic of death. The liberation wrought by Christ has freed us from all obligation to sin.

The verb "to kill" used by Paul to speak of the actions of sinful man reveals the radical nature of spiritual combat. It is not a matter of gradually improving our behavior, but of putting to death what belongs to the old regime. This spiritual violence is only possible "by the Spirit," Paul specifies. Christian asceticism is never a purely human effort, but a cooperation with the divine power at work within us.

The decisive turning point of the passage comes with the affirmation of sonship: "You have not received a spirit of slavery." Here Paul identifies the heart of the human problem: fear. Humanity naturally lives in fear before God, fear of judgment, punishment, abandonment. This fear engenders inner slavery, the psychological servitude that paralyzes existence.

The Spirit received produces the opposite effect: it generates filial freedom. This freedom does not consist of doing what one wants, but of living in trust, without the terror that characterizes the slave. The child sometimes makes mistakes, even disobeys, but he knows that he remains a child, that his identity does not depend on his performance.

The cry "Abba! Father!" is the culmination of this transformation. Paul uses the verb "crazo," which evokes a powerful, spontaneous cry from the depths. It is not a polite recitation, but a welling expression of inner recognition. The Spirit himself utters this cry through us, testifying to our own spirit that we have become children of God.

This inner attestation deserves attention. Paul is not talking about theoretical knowledge or an intellectually accepted doctrine. The Spirit attests, that is, produces an existential certainty, a deep conviction that transforms our perception of ourselves and of God. This certainty is not proud but peaceful; it frees us from spiritual anxiety.

The freedom given by the Spirit: moving beyond the logic of performance

The first dimension we must explore concerns the very nature of this spiritual freedom announced by Paul. Too often, we reduce the Christian life to a list of commandments to observe, practices to perform, and sins to avoid. This approach, although it contains some truth, misses the essential Pauline message.

To live "according to the flesh," in Paul's vocabulary, means to organize one's existence around one's own resources, one's natural abilities, one's personal will. This logic paradoxically leads to failure and death, not because human effort is inherently bad, but because it cannot achieve the inner transformation that only God can bring about. Man left to his own devices goes around in circles, repeats the same patterns, and remains a prisoner of his limitations.

The Spirit introduces a radically different dynamic. He does not simply assist our efforts or strengthen our will. He produces in us what we cannot produce on our own: divine life, Christlikeness, the capacity to love as God loves. This action of the Spirit does not remove our responsibility, but it places it in a different framework: we cooperate with a grace that precedes and accompanies us.

The metaphor of killing the actions of sinful man reveals an often overlooked aspect of Christian spirituality. It is not a war against ourselves that leads to a hatred of our humanity. The enemy is not our bodies, our emotions, or our desires, but the dynamics distorted by sin: the pride that isolates us, the selfishness that turns us inward, the jealousy that poisons us, the fear that paralyzes us.

This killing is carried out "by the Spirit," Paul specifies. We are not abandoned to our own strength in this fight. The Spirit acts as a transforming force that gradually modifies our deepest desires, renews our motivations, and purifies our intentions. This divine action respects our rhythm and our limits; it does not violate us but frees us little by little.

Filial freedom is fundamentally different from license. It is not permission to do whatever one wishes, but the rediscovered ability to choose the good out of love and not constraint. The child obeys differently from the slave: not out of fear of punishment, but out of trust in the father's wisdom, out of a desire to resemble him, out of gratitude for his love.

This freedom is experienced concretely in daily moral life. Faced with temptation, the Christian animated by the Spirit does not simply resist by will. He discovers a deeper desire, that of communion with God, which puts the attraction of sin into perspective. The spiritual struggle becomes less a fierce battle against oneself than a progressive orientation toward a greater good that attracts and liberates.

Intimacy Restored with God: Rediscovering Filial Prayer

The second essential dimension of our text concerns the relationship with God itself. The transition from slavery to sonship radically changes our way of praying, of considering God and of living our faith on a daily basis.

The spirit of slavery that Paul evokes produces a religion of fear. God becomes a severe judge, a merciless overseer, an accountant who records every fault. This image of God, although it contains some truth concerning divine justice, distorts Christian revelation. It engenders an anxious spirituality, obsessed with perfection, incapable of inner peace.

Religious fear paralyzes prayer. The slave approaches his master with trembling, calculates his words, awaits the verdict. His prayer becomes formal, recitative, distant. He recites learned formulas, performs prescribed rites, but does not truly encounter God. The heart remains closed, protected behind external observances.

The Spirit of adoption transforms this dynamic. He produces in us the ability to say "Abba," the word that only Jesus spoke with such confident simplicity. We do not appropriate a title that is foreign to us, but the Spirit makes us share in the very relationship that the Son has with the Father. It is he who cries out in us, by us, through us.

This filial prayer is characterized by spontaneity. The cry "Abba" is not a skillfully composed liturgical formula, but the immediate expression of an inner gratitude. It springs from the heart without calculation, without elaborate preparation. The child does not think long before calling his father; he does so naturally, in need as well as in joy.

Intimacy with God does not mean disrespect or misplaced familiarity. The word "Abba" in the Aramaic language combined tenderness and respect. The child honors his father precisely because he knows and loves him. This personal knowledge establishes a genuine reverence, quite different from servile fear.

Christian prayer becomes a living dialogue. We no longer speak to a distant God who perhaps hears us, but to the Father who listens to us attentively, who cares about us, who intervenes in our existence. This certainty transforms our way of praying: we dare to ask, we accept to complain, we share our joys, we present our real needs and not pious and artificial requests.

The inner witness Paul mentions becomes a concrete spiritual experience. In filial prayer, we sometimes perceive the presence of the Spirit bearing witness to our spirit. It is not necessarily an extraordinary or mystical experience, but a profound peace, a gentle certainty, a confidence that settles in despite difficult circumstances. We know that we are heard, that we are not alone, that the Father watches over his children.

The Promised Inheritance: Living Already in the Perspective of Glory

The third dimension of our text opens onto the future and gives our present existence its ultimate direction. Paul does not simply affirm our present filiation, he draws its eschatological consequences: we are heirs, called to share the glory of Christ.

The vocabulary of inheritance had a concrete meaning in the Roman world. The heir received not only the material goods of the deceased, but also his name, his social status, his place in society. Paul transposes this legal reality to the spiritual plane: we inherit God himself, his nature, his life, his glory.

This perspective of inheritance transforms our understanding of Christian existence. We do not live simply to improve the present or keep commandments, but to prepare ourselves to receive a fullness that surpasses all imagination. This hope is not an escape from the real world, but a strength that gives meaning and courage in the face of current difficulties.

Paul, however, introduces a condition that may be surprising: "if indeed we suffer with him." This clarification does not call into question the gratuitousness of adoption, but emphasizes that conformation to Christ necessarily passes through the cross before the resurrection. The heir shares the destiny of the one he inherits: if Christ suffered, we will also suffer.

This suffering "with Christ" does not refer to just any difficulty in existence. Paul speaks of a voluntary sharing of Christ's destiny, of an acceptance of the trials linked to Christian witness, of a solidarity with the Crucified One in our own flesh. This perspective gives meaning to the inevitable sufferings of life and transforms our way of experiencing them.

The hope of glory does not project us into a distant and abstract future. It influences our present by putting current difficulties into perspective. As Paul will write immediately after our passage, the sufferings of this present time are nothing compared to the glory that will be revealed. This comparison does not minimize the reality of suffering, but places it in a broader perspective.

The promised glorification concerns our entire being. Paul is not speaking of a disembodied survival of the soul, but of a complete transformation of our person, including the body. Christ's resurrection prefigures our own resurrection. We are called to share not only his spiritual life, but also his bodily glory, in a renewed world.

This hope gives impetus to our moral and spiritual life. We do not resign ourselves to present mediocrity, but we train ourselves now to live as children of God, to manifest the first fruits of future glory. The Christian virtues become the apprenticeship of a glorious existence, the preparation for a life fully reconciled with God and with creation.

Tradition: how the Church meditated on this text

This passage from the Epistle to the Romans has profoundly influenced Christian spirituality throughout the centuries. The Fathers of the Church recognized in it one of the foundations of their theology of divinization, the doctrine according to which man is called to participate in the divine nature.

Saint Augustine, in his commentaries on the Epistle to the Romans, emphasizes the role of the Spirit in making us cry "Abba." He emphasizes that this prayer does not come from our own strength but from divine grace at work within us. Augustine sees in this filial cry the proof of our inner transformation: we do not pretend to be children of God, we truly are by the action of the Spirit.

Saint Thomas Aquinas, in his Summa Theologica, develops the notion of divine adoption, drawing heavily on this Pauline text. He explains that human adoption does not change the nature of the adopted child, while divine adoption truly transforms us, making us participants in the divine nature. This distinction helps us understand the radical nature of Christian filiation: we are not simply declared children, we actually become them.

Benedictine spirituality has particularly valued the prayer "Abba," seeing it as the purest expression of filial humility. In the Rule of Saint Benedict, the monk's prayer should be brief and pure, springing from the heart rather than multiplying words. The cry "Abba" perfectly embodies this ideal of simple and trusting prayer.

The Church's liturgy has integrated this theme of filiation into several key moments. The prayer of the Lord's Prayer, before Communion, is preceded by an introduction that explicitly repeats this passage: "As we have learned from the Savior and according to his command, we dare to say: Our Father..." This verb "to dare" reminds us that we can only call God "Father" by the grace of adoption.

Christian mystics found in this text a confirmation of their deepest spiritual experiences. Teresa of Avila describes how, in deep prayer, the soul truly feels itself a daughter of God, with a certainty that surpasses all intellectual reasoning. John of the Cross evokes this action of the Spirit who prays within us and makes us participate in the Trinitarian life.

Contemporary theology continues to explore the riches of this passage. Reflection on the economic Trinity, the one revealed in the history of salvation, is based on this action of the Spirit who makes us cry out "Abba." We thus enter into the mystery of Trinitarian relationships, not through abstract speculation, but through concrete spiritual experience.

Meditation: living filiation on a daily basis

To embody in our ordinary lives this reality of divine filiation, here is a progressive path in seven stages, each illuminating a practical dimension of our filial relationship with God.

Start the day as a child of God. As soon as we wake up, before we check our messages or plan our activities, let's take a moment to remind ourselves of our true identity. Simply whisper "Abba, Father" and let this word sink into us. This practice immediately refocuses our awareness on what matters most: we are loved before we perform.

Praying with spontaneityThroughout the day, let us dare to speak to God as to a father, without complicated formulas. Let us share with him our real worries, our simple joys, our questions, our needs. This spontaneous prayer develops intimacy and unravels the blockages of formal prayer.

Discerning the Movements of the SpiritLet us learn to recognize the inner inspirations that guide us toward goodness, peace, and charity. The Spirit guides us gradually if we pay attention to these discreet movements. A spiritual journal can help us identify these divine actions in our daily lives.

Accepting paternal correctionsA loving father educates his children. Rather than rebelling against difficulties or failures, let us seek what God wants to teach us. This attitude transforms trials into opportunities for spiritual growth.

Cultivating Confidence in Difficult TimesWhen anxiety mounts or circumstances overwhelm us, let us repeat to ourselves, "Abba, Father, you watch over me." This simple prayer combats fear and restores inner peace. It redirects our focus from our problems to God's care.

Living as heir to the KingdomOur daily choices, even the smallest ones, prepare our entrance into glory. Choosing generosity over selfishness, truth over lies, service over domination: these decisions gradually configure us to Christ and prepare us for the promised inheritance.

Meditate regularly on our filial dignityLet us take time each week to meditate on Paul's text. Let the words "you are children of God, heirs with Christ" resonate within us. This contemplation gradually transforms our image of ourselves and our relationship with God.

Conclusion: the audacity of filiation

The passage from the Epistle to the Romans we have explored reveals a spiritual revolution whose full consequences we may not yet fully appreciate. Paul is not simply proposing an adjustment in our religious life, but a complete transformation of our identity. We are no longer anxious slaves seeking to appease a capricious master, but trusting children welcomed by a loving Father.

This divine filiation is not a pious metaphor or a sentimental consolation. It constitutes the deepest reality of our Christian existence. The Holy Spirit himself dwells within us and testifies to our spirit that we belong to the family of God. This inner certainty, when lived authentically, transforms the way we pray, struggle against sin, face trials, and hope for future glory.

The path proposed by Paul, however, requires active consent on our part. The Spirit does not transform us in spite of ourselves, as if by magic. He expects our cooperation, our docility, our openness to his action. Killing the actions of sinful man "by the Spirit" means collaborating with divine grace, welcoming his purifying work, accepting the challenges it implies.

The invitation is radical: let us dare to live as children of God, not only in our moments of prayer, but in all dimensions of our existence. This filial audacity will transform our human relationships, our professional commitments, our ethical choices, our way of inhabiting the world. We will become living witnesses of God's paternal tenderness, demonstrating through our joyful freedom that the Gospel is not a burden but a liberation.

The promised inheritance awaits us. The glory we will share with Christ surpasses anything we can imagine. But this hope is not an excuse to flee the present. On the contrary, it engages us in God's today, urges us to live now as heirs of the Kingdom, to manifest in our concrete lives the first fruits of renewed creation.

May the cry “Abba, Father!” become the breath of our soul, the spontaneous expression of our heart transformed by the Spirit. It is in this filial simplicity that true Christian wisdom unfolds, that which configures us to Christ and prepares us for eternal communion with God.

Practical

Morning prayer : Begin each day by whispering “Abba, Father” before any other activity, to anchor your identity in divine sonship.

Filial examination of conscience : Every night, ask yourself if you have lived as a child of God or as a slave to fear and constraints.

Practice of trust : In moments of anxiety, repeat to yourself, “My Father watches over me,” to combat the spirit of servile fear.

Meditative reading : Reread Romans 8 each week, noting in a notebook the inner movements aroused by this text.

Spontaneous prayer : Speak to God throughout the day with the simplicity of a child speaking to his father, without complicated formulas.

Daily discernment : Identify an inspiration from the Spirit received during the day and note how you responded or resisted it.

Legacy Orientation : Every important moral decision, however small, think of it as a preparation for your entry into the promised glory.

References

Epistle of Saint Paul to the Romans, chapter 8, verses 12-17, main source text of this meditation on divine filiation and the action of the Holy Spirit.

Saint Augustine, Commentaries on the Epistle to the Romans, patristic analysis of divine grace and filial adoption in Pauline thought.

Saint Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, IIa-IIae, question 45 on the gifts of the Holy Spirit and the nature of divine adoption truly transforming the believer.

Teresa of Avila, The Interior Castle, a mystical exploration of intimacy with God and the experience of divine sonship in deep prayer.

John of the Cross, The Ascent of Carmel, reflection on union with God and the action of the Spirit who makes us participate in the Trinitarian life.

Catechism of the Catholic Church, paragraphs 1996-2005 on justification and 2777-2785 on the prayer of the Our Father as an expression of filial trust.

Romano Guardini, The Lord, meditations on the prayer of Jesus and the meaning of the word “Abba” in Christian revelation.

Hans Urs von Balthasar, The Theology of History, theological development on filial adoption and participation in Trinitarian life through the Holy Spirit.